From T-Shirts to Skateboards: The Growing Demand for Pop Art Merchandise

Pop Shop I, Plate I © Keith Haring 1987

Pop Shop I, Plate I © Keith Haring 1987

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

From Andy Warhol t-shirts from Uniqlo to Keith Haring earrings from Pandora and Jean-Michel Basquiat phone cases from Casetify, our appetite for artist merchandise has never been stronger. Born out of Pop Art, a movement shaped by consumerism, art and artists are increasingly conflated with brands themselves.

Here, Richard Polsky explores the market for Pop Art merchandise in the 21st century, and its role in shaping the way we appreciate and experience art today.

Exploring the burgeoning market for Pop Art merchandise, Erin-Atlanta Argun sits down with Richard Polsky in this episode of MyArtBroker Talks to discuss the art historical and cultural significance of Pop Art merchandise.

Listen to the complete podcast here:

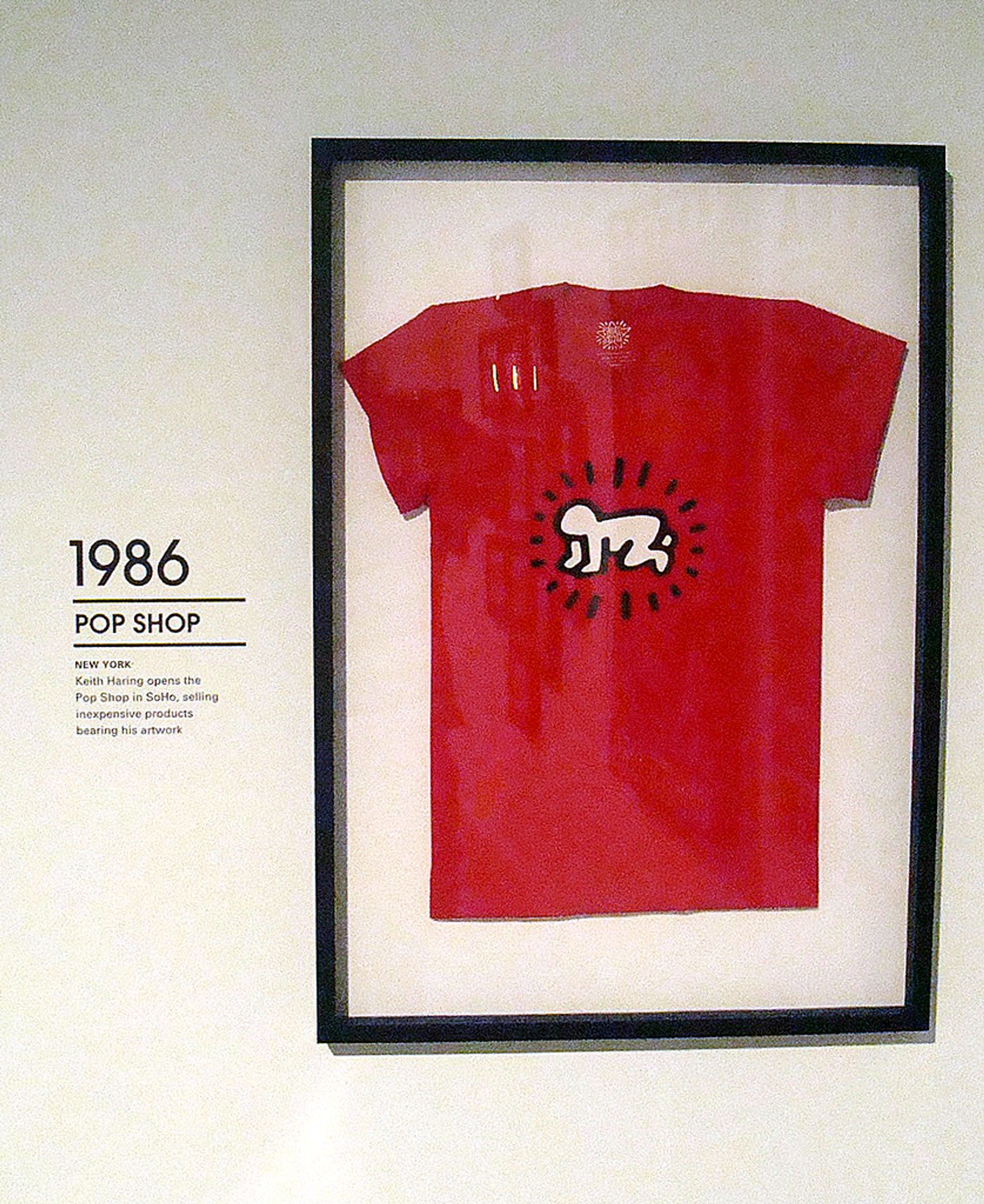

The Art Merchandise Juggernaut

In 1988, I wandered off the streets of New York’s SoHo arts district into Keith Haring’s original Pop Shop. The store was stocked with a blizzard of merchandise; everything from a Keith Haring radio to tiny metal badges. The radio was relatively expensive (perhaps $99). But the colorful badges, which depicted Haring icons like barking dogs and crawling babies, might have been a mere seventy-five cents each. There was something for everybody and every budget. Here was Haring’s “art is for everyone” philosophy on display in full force.

A Keith Haring Watch by Swatch Watches

A Keith Haring Watch by Swatch WatchesWhat really blew me away were the Keith Haring Swatches. They were the perfect marriage of art and commerce. Allegedly, Swatch initially approached Warhol to design a timepiece for them. But he told them he was too busy and recommended Haring for the job. As I look back, I realised that I should have bought one; I don’t know what stopped me. Part of it might have been guilt. After all, I fancied myself a serious art dealer and collector. What it probably came down to was that I wasn’t emotionally ready for the artist merchandise revolution which was beginning to ferment. I had no idea that Keith’s Pop Shop wasn’t just a one-time experiment — it was a harbinger of the future.

My doormat, featuring one of Keith Haring's Barking Dogs in blue

My doormat, featuring one of Keith Haring's Barking Dogs in blueFlash forward to present times. I recently moved to a new home and was looking for a cool doormat to decorate my front porch. My wife showed me a “hipster” furniture catalog which advertised a vibrant Keith Haring doormat. It featured a sky blue barking dog and was priced at $175. Now here was a dilemma. I thought, Do I really want to be one of those people who buy artist products? Then again, I was in the market for a doormat and I was a Haring fan. How could I go wrong? I bought the doormat.

Naomi Campbell wearing a Calvin Klein x Andy Warhol trench coat, from the 2018 Pre-Fall collection

Naomi Campbell wearing a Calvin Klein x Andy Warhol trench coat, from the 2018 Pre-Fall collectionAndy Warhol x Calvin Klein: An Ongoing Collaboration

My Haring purchase made me take a deeper dive into other artist-driven merchandise. I was already aware that Calvin Klein had acquired the licensing rights to a slew of Warhol classic images from the 1960s to transform into dress designs. The finished products, as you would expect from Calvin Klein, were tasteful. The obvious question is what would Andy have thought if he was still alive. The answer is equally obvious — if it made money he was all for it.

Cover of Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure © Rizzoli International Publications 2022

Cover of Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure © Rizzoli International Publications 2022The Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure Emporium

I began taking a look into the Niagara of Jean-Michel Basquiat products. If ever a famous artist estate tried to capitalise on a potential revenue stream, it was the Basquiat estate. Recently, the Basquiat sisters (Jeanine Heriveaux and Lisane Basquiat) organised a tremendous traveling exhibition called “King Pleasure.” The show’s premise was to share with the public the family’s collection of Basquiat works, including Jean-Michel’s personal stash of objects he had collected; video cassettes, trading cards, African carvings, alongside countless other artefacts. King Pleasure also featured a substantial exhibition catalogue that was well-researched and fun to read.

Coach x Basquiat Square Bag B4/Black - Andy Warhol © Coach

Coach x Basquiat Square Bag B4/Black - Andy Warhol © CoachWhile exhibition ticket sales were apparently strong, the real financial action took place at the Jean-Michel Basquiat King Pleasure Emporium. This was a slick online site crammed with Basquiat merchandise, all of it licensed by Artestar. The menu had multiple categories which ranged from objects for the home to fashion accessories. The pricing, while not cheap, seemed reasonable. For instance, you could buy a Coach bag illustrated with a painting Jean-Michel once did of Andy Warhol “as a banana.” Price: $795. There were also the usual array of skateboard decks ($220 each) and decorative items for the home, such as a throw which depicted a line drawing of a skull ($398). The point is the majority of the products were in surprisingly good taste.

A guess is that the King Pleasure Emporium will serve as a future model for an estate looking to capitalise on licensing products. Granted, not all artist imagery lends itself to reproduction. Can you imagine the limitations of the concentric square imagery of Josef Albers? Yet, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that the Basquiat sisters have hit on something: Why sell irreplaceable paintings from Jean-Michel’s estate when there’s plenty of money to be made from a renewable resource.

Roy Lichtenstein Stamps © U.S. Postal Service 2023

Roy Lichtenstein Stamps © U.S. Postal Service 2023The Low Profile Approach of the Roy Lichtenstein Estate

On the other hand, not every estate has chosen to cash in. The Roy Lichtenstein Estate has preferred to keep a low profile. Dorothy Lichtenstein, the artist’s widow, has done a thoughtful job of placing works from the estate with the Whitney Museum of American Art. This includes both paintings and a “study collection” of historic ephemera and small works. She also donated to the Whitney the building which housed Roy’s studio. About the only “merchandise” she approved were a set of United States postage stamps which reproduced a variety of Roy’s paintings. The bottom line was that the Roy Lichtenstein Estate was more concerned with the artist’s legacy than money.

The Future of Art Merchandise and Fashion Collaborations

So where does this leave the future of artist merchandise? One possible development is the opening of a chain of shops dedicated to an individual painter. They might even be sold as franchises. Much like Apple, which originally only sold computers through “resellers” or through their own website, they eventually opened an international group of retail stores — which are now ubiquitous.

Art is becoming increasingly about branding. This is something Sotheby’s and Christie’s have successfully achieved. When I bought a home in Santa Fe, I bought it through Sotheby’s. This was not a “snob” move on my part. Rather, it was the simple recognition that their brand was synonymous with quality. In fact, the hardest task for a famous artist estate will be finding a way to build their brand so it shouts “quality” across the room.

One strategy for brand recognition might be to concentrate exclusively on high-end merchandise. Keith Haring’s philosophy of being as inclusive as possible made it logical to include plenty of inexpensive “stuff” at his Pop Shop. However, other big-time artists would be ill-advised to use that approach. Instead, it would seem far better for estates to aim high — like how the Warhol people worked with Calvin Klein — when it comes to licensing a respective artist’s work. There will always be a market for first-rate art-related products.