What Do Auction Results Really Tell Us About the Value of Art?

The Arrival Of Spring In Woldgate East Yorkshire 18th January 2011 © David Hockney 2011

The Arrival Of Spring In Woldgate East Yorkshire 18th January 2011 © David Hockney 2011Market Reports

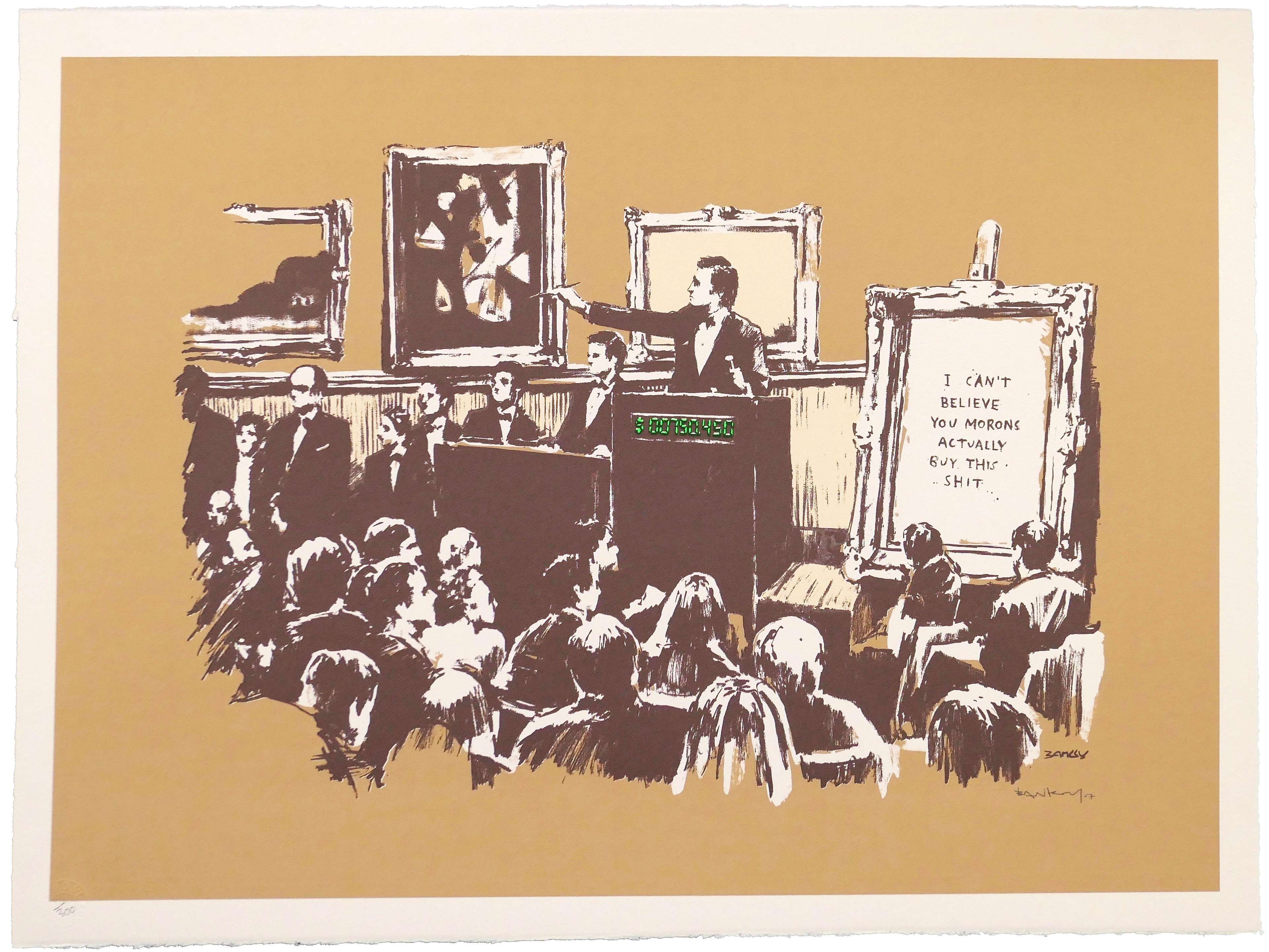

The world of prints is often held up as the neat, rational corner of the art market. And it’s true – to an extent. A Banksy, Hockney or Warhol edition may have appeared at auction 20, 50, 100 times. We can chart its performance. We can compare apples with apples. It’s data-rich, and that creates the illusion of certainty.

The Illusion of Objectivity in the Value of Art

That structure allows us to build valuations grounded in public auction results, add certainty via comparables like relationships between colourways, and even the print series connection to the originals market. It gives buyers confidence and sellers reference points. And it gives platforms like ours a foundation to work from, through machine learning and specialist insight.

But step into the world of originals, and that scaffolding falls away fast.

Recently, I had a conversation with a highly active dealer in the Originals market and they put it plainly: “With originals, it’s often just instinct. Gut feel. Market mood. You can’t always justify it with data.”

That’s not a flaw – it’s just the nature of the beast. A one-of-a-kind Hockney drawing or a rare Bridget Riley painting doesn’t have a neat comp set. You're reading the metaphorical room, gauging the demand of buyers based on conversations and market conditions, and sometimes, just taking a leap of faith based on the desirability of the work, and the cornerstone of the artist market over a number of years.

What Happens at an Auction Valuation?

When you approach an auction house for a valuation, you're entering into a process that's as much about sales strategy as it is about assessing value. Specialists will examine your artwork, considering factors like provenance, condition, and recent auction results for comparable pieces. They'll provide an estimate, often presented as a range, which is influenced by their desire to secure the consignment and stimulate competitive bidding. The net return to a vendor will often be subject to fees, not just sellers commission but various other costs of sale. You can find out more about that here.

This estimate isn't solely a reflection of market value; it's also a marketing tool designed to attract interest and encourage bidding. The artwork's placement within an upcoming sale, the timing of the auction, and the presence of similar works can all impact the valuation. For example, in the recent New York May sales, Roy Lichtenstein’s original drawing on paper The Kiss was offered with a presale estimate of $7-9 million. The work ultimately performed a notable amount below that range, achieving $5.4 million with fees. While still a respectable result, coming in below expectations likely reflected the upcoming availability of comparable Lichtenstein originals and editions from Dorothy and Roy Lichtenstein’s personal collection in Sotheby’s subsequent sale. It’s a reminder of the auction process and calendar - how the proximity of similar works can influence both perceived value and final results.

That’s not to say this process isn’t useful – but it’s far less candid and far less reflective of the actual return a seller might achieve than in a private sale. At MyArtBroker, we agree on a single, fixed net return with our sellers. It’s a simpler, more transparent process. There are no moving targets, no performance-based pricing games – just a clear agreement and a dedicated specialist working to deliver the best price in the current market.

Let’s talk about valuations at auction: estimates are rarely neutral.

Auction houses routinely set low estimates to stir interest. They’re not necessarily trying to reflect fair market value – they’re creating a sense of urgency and opportunity. It’s marketing, not maths. A classic Warhol screenprint might be listed at £30,000 - £40,000, not because that’s what it’s worth, but because the house wants bidding to start fast and escalate quickly.

When it hammers at £55,000, everyone celebrates. Strong result! Market’s up! But let’s be honest - that “beat the estimate” narrative was baked into the strategy from the start.

Then there’s the other side: reserves set too high, often against the advice of the house, because a seller insists on a certain return, or no deal. That’s where no-sales creep in - not because the work isn’t valuable, not because it’s not in demand, or quality, but because the estimate was disconnected from reality.

I’ve seen incredible Riley prints and even A-grade Warhol editions fail to sell, not due to lack of demand, but due to overreaching estimates. But the damage is done – the piece looks stale, the market hesitates, and the perception shifts.

The Invisible Influence of Auction

One of the most overlooked aspects of auction results is what else is being sold at the same time.

If there are two works from Hockney’s The Weather Series in the same auction, one in flawless condition and one slightly less so, you can bet the weaker one will underperform. Not because it’s undesired, but because buyer energy gets split. Conversely, a unique Keith Haring work that’s the only one of its quality in a sale might catch a bidding frenzy simply by standing alone.

Even timing and order within the sale matters. If a top-tier Hockney piece appears early and sets the room on fire, buyers may have already spent their budget by the time a Warhol comes around. Or vice versa. These are real forces – invisible on a spreadsheet, but wildly influential in practice.

Yet when analysts publish their neat roundups, they strip all that context out. And what’s left? A number. And sometimes a misleading one.

Why Auction Results Only Tell Part of the Story in Art Valuations

It’s estimated that auction blue chip print sales represent just 34% of total market activity. The rest? It’s happening privately, between collectors, dealers, advisors, and brokers. Quietly. Discreetly. And often for significantly different prices than what we see on the public stage. It’s a slightly fairer market in that sense, not if large commissions are in place, but with the right seller the seller often returns more, and the buyer pays a more fair market price for the work.

Take Hockney’s Arrival Of Spring series. Yes, the print market is highly visible at auction – but his most serious collectors are transacting off-platform, where negotiation, trust, and timing rule the day. Especially in a market softened by ongoing volatility, context is everything. When a client sees a Hockney Lithographic Pool Print go unsold, or a Warhol Mick Jagger or Queen Elizabeth print barely meet its estimate and asks why the result seemed ‘low’, the most truthful answer lies in the nuances: condition, edition number, timing and competing works. But more broadly, the reality is the market is tight! If a seller doesn’t need to go to auction right now, many simply won’t. They don’t want to consign a work, wait months for the auction sale, and then risk a no sale - especially if they’re trying to release liquidity quickly. Instead, private transactions are increasingly the preferred route, with the latest UBS/Art Basel Report noting a 14% rise in private sales in 2024, even as public sales declined.

The point is, if you’re relying exclusively on auction results to understand the value of a work, you’re only looking at a third of the picture. By no means an insignificant part of the picture, and the reason we track over 400 auction houses to bring every result into our valuation thinking, but crucially we also know what dealers are offering, other private collectors are asking and what a prints unique value ‘DNA’ really represents in the market right now.

At MyArtBroker, we don’t just crunch numbers. We ask: what’s the condition of the piece? How rare is it? What else is on the market right now? Where has it been? Who’s buying? What does it represent, what were collectors offering when we sold this three months ago, where does the demand sit for other works in the series, how is the originals market doing? And beyond that, we layer in the broader context – the artist’s reputation, the work’s artistic significance and style, its size and complexity, provenance, subject matter, recent media exposure, whether it's been exhibited or is part of a known trajectory, and how galleries and dealers are positioning similar works. We look at geographic trends too – what’s happening in London isn’t always what’s happening in LA. And yes, of course, we look at auction results – but always as one piece of a much bigger puzzle. Ultimately, collector demand and even emotional appeal play a huge role. No two valuations are the same, because no two moments in the market are either.

The same work can do wildly different things depending on when and where it’s offered in a public auction. In a focused, well-curated sale, it might exceed all expectations. But placed in a bloated, scattergun-style evening auction? It could disappear in the noise. That nuance doesn’t show up in a sales database – but it makes all the difference to buyers and sellers alike.

This human layer of analysis is crucial, and more necessary than ever as the market grows more sophisticated. It’s also why our specialist team were all trained and have spent years at the four big auction houses before they come to us, there is no better training ground to understand the complexity of public auction valuations and estimates.

So What Are Auction Results Good For?

Let me be clear: auction results still matter hugely. Especially in the secondary market for blue prints and editions. For artists like Banksy, Warhol, or Riley, Hockney, Emin, Lichtenstein, Frankenthaler, Hirst, the list goes on, where there’s high volume and repeated public sales, they’re a useful barometer. They help set expectations. They shape sentiment. But they’re not gospel. And they’re certainly not a clear steer. Sometimes, they even distort the story, when estimates are gamified, when lots are poorly placed, or when the wider market mood isn’t factored in.

That’s why valuations at auction need to be handled with care. They’re a data point, and a good one, but not a valuation in themselves. Context, condition, timing, market feel, and strategic positioning all matter just as much, if not more. If it was as easy as that, we wouldn't have built an algorithm that defines some of those 40 plus factors that shape a work’s value, and have built a business that places human specialism at its centre.