Keith Haring's Art and the Emergence of Street Art in the 1980s

Image Keith Haring, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons / We Are The Youth Keith Haring 1987

Image Keith Haring, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons / We Are The Youth Keith Haring 1987

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

In the 1980s, the art world was undergoing a seismic shift. The graffiti art movement – once considered a form of vandalism – was gaining recognition as a valid form of artistic expression. Keith Haring was at the forefront of this transformation, merging the divide between high art and street culture, shaping the emergence and evolution of street art during that era. Characterised by its bold lines, vibrant colours and dynamic figures, his art created a visual language that was accessible, communicating its meaning to a diverse audience, irrespective of their cultural, social or educational backgrounds. The accessible nature of Haring’s art was and remains a bold reflection of his unique artistic vision and a powerful expression of his socio-political views.

Image © Rob Bogaerts (Anefo), CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image © Rob Bogaerts (Anefo), CC0, via Wikimedia CommonsKeith Haring's Pivotal Role in the Emergence of Street Art in the 1980s

Soon to be an iconic figure in the 1980s art scene, Keith Haring’s art first received public attention due to its prominence in subway spaces. As Haring's art was also deeply intertwined with his activism, and his pieces often touched upon pressing issues of the time, his art became synonymous with the growing dissident voice regarding many pressing issues, particularly those that were taboo in more mainstream media or art– racism, HIV/AIDS, homosexuality and capitalism. By moving beyond traditional gallery spaces and taking his art to the streets, Haring gave these issues a public platform, amplifying their visibility and sparking conversations that transcended the art world. The 1980s, marked by Haring's vibrant style, signified the emergence of street art as a legitimate and influential form of artistic expression– thanks, in part, to its prescience on important social causes– forever transforming the landscape of contemporary art. Nevertheless, the influence of Haring’s work is not limited to his time, and his approach continues to inspire generations of street artists.

Understanding Keith Haring’s Activist Impulse

Keith Haring was born on May 4, 1958, in Reading, Pennsylvania, and grew up in nearby Kutztown. He was exposed to the power of visuals from an early age, partly thanks to his father Allen Haring, who was an amateur cartoonist and engineer. Keith was drawn to the world of art, particularly to the realms of cartoons and animation, and an early immersion in graphic art clearly played a significant role in shaping his later artistic style.

In 1976, Haring enrolled in the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh, although he quickly realised that it was not the right fit for him. He moved to New York City in 1978 to attend the School of Visual Arts (SVA), where he was exposed to the thriving alternative art community. During this time, Haring became immersed in the city's street culture, befriending fellow artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf. He was also deeply influenced by the burgeoning graffiti movement.

Haring began to create his art in public spaces, drawing chalk figures on empty advertising panels in subway stations. His distinctive style quickly gained attention and popularity. He went on to create large-scale murals, paintings and sculptures, often using his art as a platform for social and political activism. His work addressed issues such as the AIDS crisis, nuclear disarmament, racial inequality and LGBTQ+ rights.

Doubtless the relationship between Haring’s political consciousness and his artistic inspirations was two-directional; cartoons have an longstanding relationship with satire, and Haring’s early exposure to them may have helped awaken his political awareness and desire for justness. Meanwhile, the pithy, easily disseminated and easily comprehended simplicity of cartoon-style art makes for a democratic and potentially unequivocal communication of political messages, making it the perfect style to convey Haring’s sympathies with many social causes.

Indeed, the democratic quality of his art was clearly of great importance to Haring: in 1986, Haring opened the Pop Shop in New York City, a store where he sold affordable art merchandise and further emphasised his commitment to making art accessible to all.

Tragically, Keith Haring’s life was cut short when he passed away on February 16, 1990, at the age of 31, due to complications from AIDS. As an openly gay man living through the stigma and fear of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Haring approached the cause as one of the most urgent and important of his life; releasing print series, creating murals, and generally raising awareness about the crisis. Though Haring supported many social causes throughout his career, his AIDS-related activism has come to be the apotheosis of his art, thanks to the scale of his contribution, but also, tragically, due to his own death from AIDS-related complication.

However, his art and activism continue to inspire and influence artists and social movements today. Both the Keith Haring Foundation, established a year before his death, which supports organisations working in the fields of art, education and HIV/AIDS awareness and research, and his art endure as a testament to art as a medium for social activism.

Image © Achim Hepp via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0 / Keith Haring’s Pop Shop 1986

Image © Achim Hepp via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0 / Keith Haring’s Pop Shop 1986The Emergence of Street Art in the 1980s: A Cultural and Social Revolution

The 1980s were a time of immense socio-cultural change, marked by significant economic, political, and social transformations: urban decay, escalating social inequalities, the AIDS epidemic, the Cold War and the proliferation of late-stage capitalism. The cultural and social context of the decade played a crucial role in the period’s means of artistic expression, aiding the emergence of street art, which challenged the norms of the traditional art world.

Street art emerged from the graffiti and hip-hop subcultures, particularly in New York, carrying their subversiveness with it as it evolved into a powerful medium of artistic expression. In the evolution of graffiti into street art, the rebellion, aimed purely at the often content-less act of daring, that was tagging grew into a fluent medium for protest and critical discourse. Quickly, the streets became a platform for anyone eager to voice and converse about their concerns and opinions. Urban landscapes became vibrant canvases filled with public discourse, hard to ignore even for those who continued to dismiss graffiti as a petty act of vandalism.

As graffiti’s ubiquity in the shared public space of a city like New York inevitably extended to form a universal backdrop for other art forms and events– becoming a vital aesthetic component of urban fashion and hip-hop music videos, for example– street art began to acquire its own individual celebrities. Street artists who gained mainstream fame, such as Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and others, helped to champion it as a legitimate form of artistic expression.

Street art's impact on the art world was revolutionary. It disrupted the traditional boundaries between the artist and the audience by making art accessible to all, not just those who frequented galleries and museums. It also challenged the notion of art as a commodity, as most street art was created anonymously and for free. Furthermore, it introduced a new aesthetic that was vibrant, dynamic and resonated with the urban experience, influencing other forms of art, fashion and music.

Ultimately, the 1980s street art movement signified not just an artistic revolution, but a social and cultural one too, reflecting the era’s complexities and challenges, and a mass desire to break free from the conservatism of art history prior.

Keith Haring's Subway Drawings

Keith Haring's Subway Drawings are some of the most iconic and significant works in his career. Created in the late 1970s and early 1980s, these drawings marked Haring’s shift from traditional art spaces to public platforms, particularly the subway stations of New York City.

Haring began creating art in the subway stations in the form of chalk drawings on empty black advertising panels. He was drawn to these spaces for their potential to reach a diverse and large audience, and Haring considered the subway as a "laboratory" for working out his ideas and experimenting with simple, yet powerful, line drawings. These works were not just mere sketches but potent political and social commentaries, dealing with complex contemporary themes and issues.

The significance of Haring's Subway Drawings cannot be overstated, and the impact on his career was profound – these drawings were Haring's first foray into public art, establishing him as a pioneer of the street art movement. They garnered him considerable attention, both from the public and the artistic community– including opportunities for large-scale works and commissions, and his work began to be featured in galleries and museums– and thus helped him transition from an underground street artist to an internationally recognised one.

Haring's subway art was democratic, speaking to and for the people of New York City.; they remain a testament to Haring's belief in art as a medium for social change and his commitment to making art accessible to all.

Keith Haring's Diverse Inspirations: Bringing together Pop and Street Art

As well as belonging to the street art movement of the 80s, Haring borrowed from Pop Art, leading to his introduction of graffiti and street art elements into the former, and vice versa. The two genres already share a natural affinity, thanks to the critical attention paid by both to mass consumerism, but Haring’s art consolidated their intersection by combining the styles and means of production of both. His art is characterised by instantly recognisable symbols as in the aesthetics of pop culture and cartoons, executed with the spontaneity of street art– often as his signature ‘one-line’ drawings. Figures like the Radiant Baby and the Barking Dog have become synonymous with his name; their endless repetition throughout Haring’s oeuvre testifies to the impact of the Pop Art movement on his art.

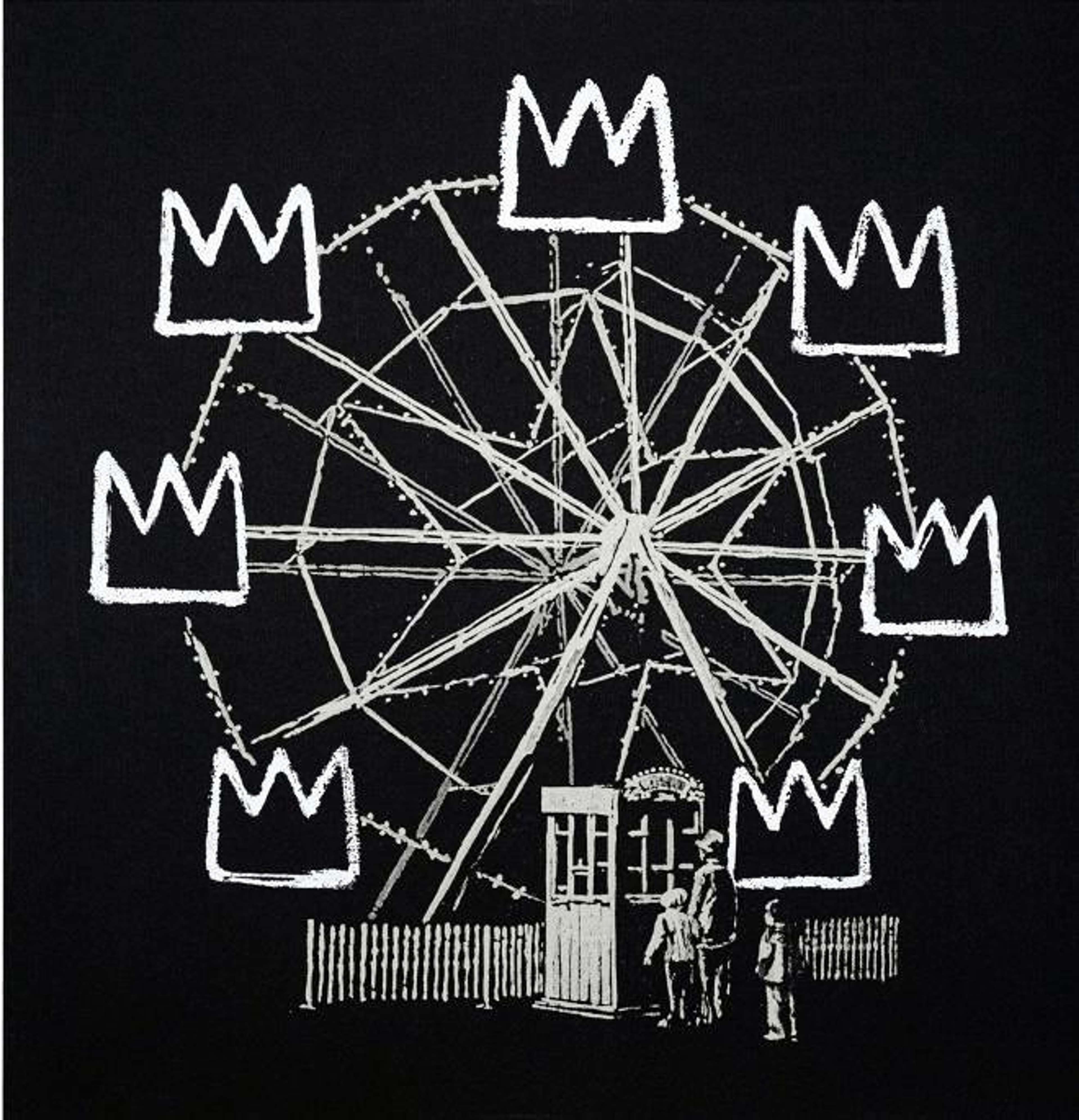

As a result of this intersection of inspirations, Haring's influence on contemporary art has been substantial: his art’s simplicity, relatability and engagement with contemporary issues made it resonate with a wide audience, influencing many artists to adopt similar approaches. Likewise, he pioneered the concept of the artist as a brand, commercialising his art through merchandise, an approach that many contemporary artists have since adopted. The influence of his Pop Art conscious street art can still be seen today in the work of the new generation’s greats such as Banksy.

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat: Embodying the 1980s NYC Art Scene

Along with Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat also played an influential role in shaping New York City's vibrant art scene in the 1980s. It is unsurprising, especially given the pair’s friendship, that their work shares a bold, expressive style and socio-political commentary, and that both challenged the conventions of traditional art and brought street art into the mainstream.

When Haring and Basquiat first met in 1979, each was drawn to the other's unique style and rebellious spirit. They shared a desire to disrupt the established art world and make art accessible to the public, leading to a deep mutual respect and friendship. This relationship resulted in several collaborations, through which they sought to bring art out of the exclusive confines of galleries and museums and into public spaces where everyone could engage with it.

Both Haring and Basquiat were deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of 1980s New York City – a period that, as we have seen, was marked by socio-political turmoil, economic inequality and the AIDS crisis. Their art mirrored these realities, serving as a powerful commentary on the issues of their time.

Their impact on the art scene was transformative. The friendship and collaboration between Haring and Basquiat not only defined the 1980s NYC art scene, but also forever transformed the landscape of contemporary art.

The Radical Joy of Keith Haring: Democratisation, Social Justice, and Art Accessibility

Haring’s art was not merely aesthetically pleasing – it was a call to action, a demand for change and a platform to raise awareness and incite conversation about the pressing issues of his time. His vibrant, dynamic figures danced, loved and protested on the same canvas, bringing critical social issues to the forefront of public consciousness in a light and joyful manner.

In essence, the radical joy of Keith Haring's art lies in its profound humanity. His belief in art as a tool for democratisation, his commitment to social justice, and his enduring legacy in promoting art accessibility all attest to his unwavering faith in art's power to transform, connect, and uplift.

While Haring's work was deeply rooted in the socio-political context of 1980s New York City, many of the themes he explored are still highly pertinent. Whether that is the product of our continued societal interest in individuality and personal sexual expression, or because issues such as racism and police brutality, sadly, remain a reality, Haring's art continues to strike a chord with global politics. Moreover, Haring's legacy continues to inspire and influence artists and activists worldwide, as it stands to remind us of the power of creative expression to challenge societal norms and catalyse change.

Finally, the use of public spaces as a canvas for art, a concept championed by Haring, is now a common practice globally. Moreover, Haring's innovative approach to commercialising art—making it accessible through merchandise—has been widely adopted in the art and fashion worlds, allowing artists to reach broader audiences and challenging the exclusivity of art ownership. To this day, he is a darling of fashion houses, which have often collaborated with his estate to maintain Haring’s mission of raising public consciousness through his work.