Building a Brain Like a Prints Specialist

MyArtBroker © 2025

MyArtBroker © 2025Market Reports

At MyArtBroker we have spent the past decade translating four decades of human expertise in the prints market into code. The result is a valuation algorithm that behaves, in Managing Director Charlotte Stewart’s words, “like a specialist who has been on the print market trading floor for forty years – only faster, always awake, and never commercially biased.” In the following interview, Charlotte explains, in plain terms, how the “brain” was built, why it sometimes even challenges MyArtBroker’s own specialists, and how its data‑driven discipline keeps the secondary market fair, liquid and transparent.

Can AI Value Art? Building A Brain Like A Prints SpecialistAlongside the algorithm sits MyPortfolio, our collection‑management tool, and the Trading Floor, a live marketplace where supply and demand are anchored to the model’s fair value. Together they create a feedback loop: every transaction refines the dataset, and every new datapoint sharpens the next valuation.

Building the Brain: Machine Learning versus “Black‑Box AI”

Q: Charlotte, you often describe the valuation engine as a “brain”. What do you mean by that?

Charlotte Stewart (CS): Think of machine learning as teaching a child to spot the difference between a Labrador and a poodle. You expose it to thousands of pictures, label them, and the child starts recognising patterns. That’s what our algorithm does with prints. It isn’t a rule‑based robot, and it isn’t a talking teddy‑bear level of artificial intelligence. It is much closer to something a financial quant would build for a trading desk: disciplined pattern‑recognition that improves with every data point.

Q: So you would place it firmly in the machine‑learning camp, not general AI?

CS: Correct. There are elements of AI embedded in the pattern‑recognition layer, but the core is supervised machine learning. We feed it verified results; it measures, scores and refines itself continuously - literally every time a print changes hands.

Why Traditional Valuations Fall Short in Today's Art Market

Q: Before we dig into how it works, why was it necessary? What is wrong with traditional valuation practice?

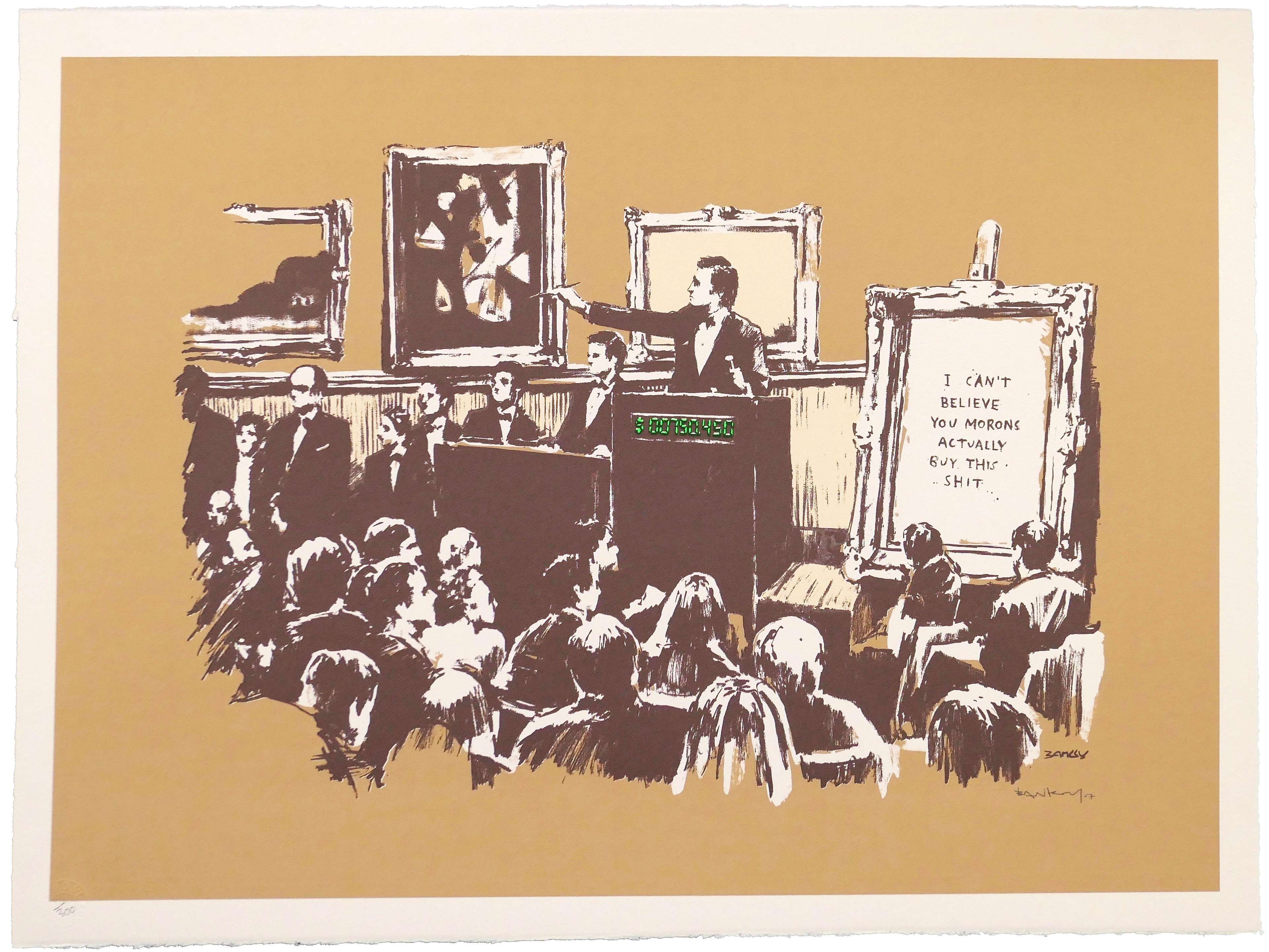

CS: Opacity, dirty data and commercial bias. In the traditional model you see only part of the picture: expert opinion, anecdotal provenance, and the top three auction houses. Fees are hidden – hammer plus buyer’s premium is published as a single ‘price’– and retail galleries can embed 50‑100 percent margins.

Take Warhol’s Marilyn prints. If you walk the high street you’ll find a high street gallery quoting half‑a‑million pounds. At the same fair a mid‑size dealer might whisper £350,000, and an online listing may sit at £275,000. None of those prices break out shipping, insurance or the 25 percent premium. For a collector the spread can top £150,000 on a single edition. That is not transparency – it is noise.

Digital platforms were meant to fix this, yet they have multiplied the problem. Anyone can harvest data, but without cleansing you end up comparing apples to steak knives. A Sunday B. Morning after‑Warhol print sits next to an authenticated original, both tagged ‘Marilyn’, and the website’s search has no idea which is which. The result is disparity that scares new entrants and erodes trust.

Q: You’ve also spoken about auction‑house incentives skewing estimates.

CS: Specialists inside an auction house live and die by sell‑through rate. That drives reserves and low estimates down: an unsold lot is a black mark. There is also a performance commission if the hammer lands above the high estimate, so the high estimate tends to be conservative. Add vendor pressure – ‘take my Marilyn but guarantee me X’ – and you have commercial bias baked into every public figure. Logical, but hardly objective.

Q: And all of that is before we touch on condition or provenance.

CS: Exactly. A Marilyn with unquestionable provenance and mint condition might achieve double the price of one that was rolled in a tube and traded ten times in five years. Yet those nuances rarely survive into a public spreadsheet.

Teaching the Algorithm to Think Like a 40‑Year Specialist

Q: Given that complexity, how did you translate a specialist’s judgment into code?

CS: We began by shadowing the best prints specialists we know – people with forty‑plus years of ‘gut feel’– and writing down every variable they subconsciously weigh. The list ran into the hundreds. The algorithm now evaluates more than forty of those at scale, but you can group them under ten headings:

- Auction results – We harvest over 400 houses globally, not just the headline three.

- Private‑sales data – Including every trade executed on MyArtBroker’s Trading Floor.

- Synthetic valuations – Every formal appraisal we issue, even when no sale follows.

- Unsold data – How often a work meets the market and is rejected.

- Comparable colourways and series relationships – Bridget Riley’s Fragment A illuminates Fragment D, just as Warhol’s African Elephant informs his entire Endangered Species series.

- Condition spectrum – Mint to damaged; we do not discard the ‘ugly’ data because the market does trade damaged works.

- Provenance and tenure – Thirty years in a private collection versus serial flipping; celebrity ownership versus anonymity.

- Macroeconomic context – Our look‑back stretches three decades, so recessions, booms and rate cycles are baked in.

- Originals‑market influence – Record‑breaking canvases ripple down into editions with a measurable lag.

- Structured feedback – The brain scores its last prediction against every new verified sale, updates its error term, and adjusts the weightings in real time.

We call that last step ‘repeat regression’. In plain language, the brain marks its own homework. A human specialist can do that once a quarter; the machine does it every few hours.

Fair‑Market First: When the Algorithm Disagrees with the Humans

Q: You’ve said the model occasionally works against your specialists. Why keep it that pure?

Because we categorically reject commercial bias. Our founders, Ian and Joe, were collectors before they were brokers; they knew what it felt like to be ‘ripped off’ by opacity. Our job is to keep this market healthy for the long term, not to ride a bubble. The brain has zero interest in margin. Sometimes that means telling a vendor their print is worth £35,000 when they want £40,000, or explaining to a buyer that £45,000 is unsustainable. It stings in the short term, but it preserves liquidity.

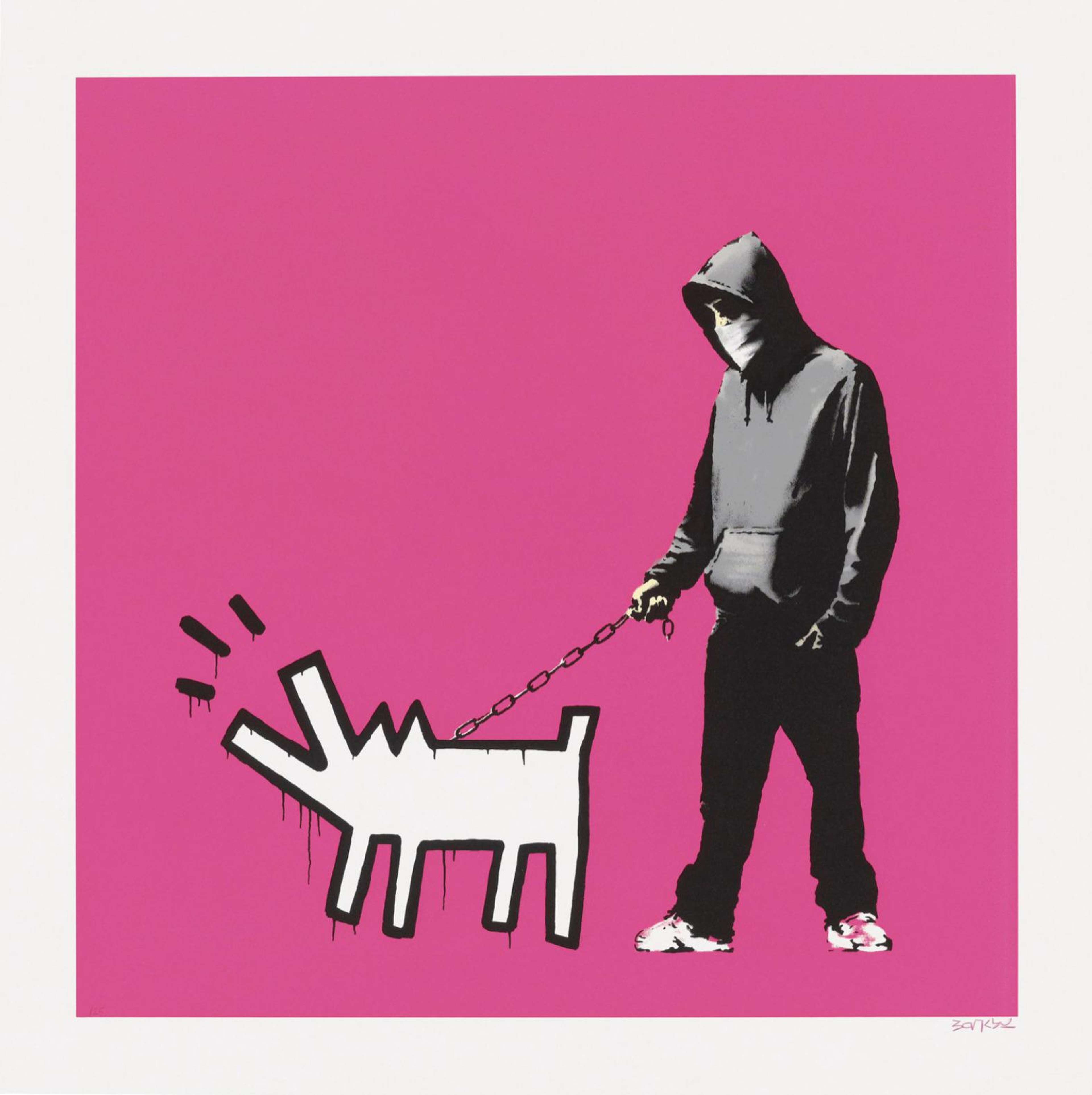

Look at what happened to the Banksy market in 2020: the major houses flooded supply to satisfy demand, prices spiked, and then the market recoiled. We can’t afford that. Prints are the backbone of our business. A transparent, data‑driven fair‑value curve is the best defence against boom‑and‑bust.

Q: Yet MyArtBroker still covers shipping, insurance, even restoration, and charges a fraction of auction’s commission schedule. How?

CS: Three reasons. First, every print is physically inspected by an independent condition specialist – no peer‑to‑peer blind shipping – because a hidden crease can move value by tens of percent. Second, our overhead is digital rather than bricks‑and‑mortar; we don’t need marble foyers to sell a Warhol. Third, we prefer repeat business to one‑off windfalls. A client who buys at a fair price today is a client who returns tomorrow, and that relationship capital is worth more than a single fat margin.

Q: Doesn’t subsidising shipping and restoration erode profit?

CS: It tightens the spread, certainly, but clarity attracts volume. Besides, most vendors would rather agree to a net return up‑front than gamble on an auction reserve. They know exactly what they’ll receive from us before the courier even collects the work.

What This Means for Collectors – and for Dealers

Q: We’ve had dealers at art fairs complain that our live site pricing is ‘too low’. How do you turn that criticism into a benefit?

It’s a challenge for dealers whose consignors expect above‑market returns. Supply is hard enough without inflated expectations. We actually invite dealers to adopt the algorithm. Imagine pricing a print in real time, armed with a fair‑value feed that adjusts the moment a fresh data point enters the system. That is the real opportunity. A dealer who can show a collector, on screen, exactly where the print sits relative to every verified sale in the past decade earns immediate credibility. They close sales faster, vendors gain realistic expectations, and the broader market – freed from inflated asks – runs smoother.

Looking Ahead: From Valuation Engine to Market Standard

Q: Where does the algorithm go next?

CS: Coverage and connectivity. We are onboarding smaller regional salesroom data, stretching back through archival catalogues, and ingesting additional private‑sale channels so the brain never stops learning. The next milestone might be an open API. Dealers, insurers, even lenders will be able to plug directly into the valuation feed and – with appropriate throttling – surface live fair‑value data inside their own platforms.

Once that infrastructure is in place, the market gains something it has never truly had: a neutral benchmark akin to a commodities index. At that point every participant, from the first‑time collector to the pension fund exploring art‑backed lending, can reference a shared, verifiable price curve.

Q: And for collectors?

CS: More confidence, faster liquidity, and, crucially, a far lower barrier to entry. Prints are already the most democratic slice of the art world; combining transparent pricing with seamless trade mechanics pushes the democratisation further.

Fair‑market discipline is not a slogan – it is the operating code that powers MyArtBroker’s algorithmic brain. By compressing forty years of specialist judgement into an always‑on, self‑correcting valuation engine, we remove opacity, resist commercial bias, and keep the prints market healthy for the long haul. Dealers, auction houses and collectors are invited to use the same data, play by the same rules, and share in a market where price discovery is no longer guesswork but grounded in evidence. The technology we have built at MyArtBroker, and our entire business model, is grounded in a mission to build a healthier ecosystem for the era-defining art of our time.