Is Art Always Trying to Sell You Something?

Life Savers (F. & S. II.353) © Andy Warhol 1985

Life Savers (F. & S. II.353) © Andy Warhol 1985Market Reports

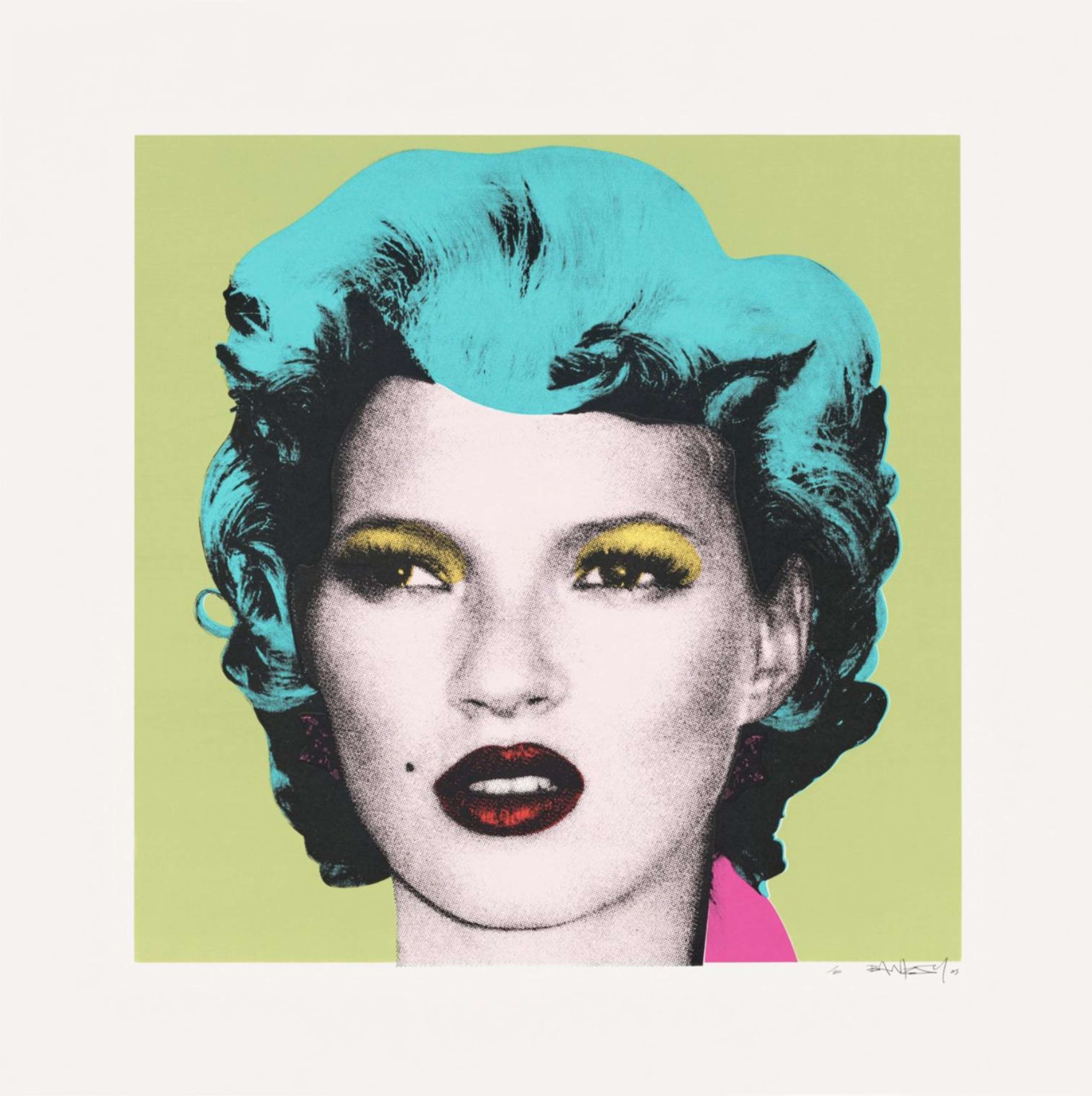

From Renaissance patronage to Warhol’s Soup Cans, art and advertising have maintained a mutually reinforcing relationship, each employing visual rhetoric to capture attention and shape perception. Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Banksy interrogated and subverted this fusion by appropriating corporate imagery, mass-media tropes, and public space to systematically blur the boundary between fine art and marketing.

Patronage and Publicity

Historically, governing bodies, religious hierarchies and affluent patrons have strategically employed artists to project power and convey ideological narratives. For example, Michelangelo’s ceiling frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, executed under Pope Julius II, functioned as a potent instrument of papal propaganda. The orchestrated sequence of Old Testament scenes culminates in the Creation of Adam, evoking divine potency and reinforcing the Church’s continuity with classical antiquity. These monumental compositions educated the clergy and laity in core Christian doctrines, while directing public sentiment toward Julius II’s vision of a reinvigorated, triumphant papacy.

Similarly, in fifteenth-century Florence, the Medici family employed Donatello’s David as a public symbol of their civic stewardship. By situating this bronze sculpture in the Palazzo della Signoria, the Medici harnessed visual symbolism to cultivate brand equity and foster civic identity. Contemporary parallels can be found in collaborations between luxury brands and living artists, in which commissioned cultural production enhances institutional prestige and circulates brand values through aesthetic practice.

Warhol & Pop: Turning Ads into Art

Andy Warhol’s transition from commercial illustrator to Father of Pop Art illustrates a deliberate fusion of advertising strategies with fine art. His early work for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and clients such as Tiffany & Co. exposed him to the disciplines of composition, repetition and iconic branding. This foundation can already be seen in his mid-1950s advertorial projects - most notably À La Recherche Du Shoe Perdu, a series created between 1955 and 1957 when he was the sole illustrator for I. Miller, producing new shoe drawings weekly for New York Times ads. At the same time, in 1957 Warhol compiled A Gold Book, a bespoke promotional portfolio in which each copy was individually inscribed by his mother, Julia Warhola, and hand-coloured at organised “coloring parties.” These projects not only demonstrated Warhol’s innovative blot-and-ink printing technique but also presaged his later treatment of everyday commodities as subjects of rigorous aesthetic examination.

Building on these commercial foundations, in 1962 Warhol debuted his Campbell’s Soup Cans; a suite of thirty-two canvases each bearing the label of a different variety of Campbell’s condensed soup. By presenting the paintings in a uniformly spaced grid - evocative of supermarket shelving or a print advertisement - Warhol transformed mass-produced consumer goods into icons of fine art. This deliberate conflation of commercial imagery and gallery display not only foregrounded the aesthetic value of quotidian objects but also prompted a critical reassessment of the boundaries between “high art” and popular culture.

Continuing his exploration of consumer culture, in 1962 Warhol also produced Green Coca-Cola Bottles, a single bottle motif repeated in rows seven high by sixteen across above the company logo. Though the overall design mimics mechanical reproduction, subtle variations, such as uneven green underpainting and small misalignments of the wood-block–stamped black outlines, ensure that each bottle retains a hand-rendered quality. Warhol’s declaration: “A Coke is a Coke, and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking”, further elevated these everyday objects into symbols of economic and social equality. By celebrating products that remain constant in quality regardless of price or purchaser, Warhol both critiqued and glorified the homogenising forces of postwar American consumerism.

This approach resurfaced in 1985 with Warhol’s Ads portfolio, a series of ten screenprints featuring corporate emblems ranging from Apple computers to Chanel No. 5 bottles. In Life Savers, Warhol showcases the candy's cheerful colours, evoking nostalgia and highlighting the intersection of childhood memories with mass marketing, while Van Heusen (Ronald Reagan) juxtaposes the U.S. President with a 1950s shirt advertisement, blending celebrity culture with political imagery. By abstracting and magnifying familiar logos, Warhol elucidated the cultural power embedded within marketing imagery and exposed the mechanisms through which brand iconography shapes collective consciousness.

Art for Everyone: Haring's Commercial Imagery

Haring’s work emerged at the intersection of street art’s immediacy and advertising’s ubiquity. In 1980, he transformed blank subway ad panels into chalk drawings, his radiant babies and barking dogs serving as pop-culture hieroglyphs in motion. These subway drawings harnessed the audience of the New York commuter by echoing the strategies of corporate branding: disrupting daily routines and conveying instant messages. By adopting the visual grammar of advertising, his art functioned like ubiquitous corporate logos by engaging everyday commuters directly. In doing so, Haring democratised art by bringing it out of galleries and into the lives of ordinary people.

This ethos of accessibility extended into Haring’s later venture, the Pop Shop, which he opened in New York City in 1986. Conceived as a physical extension of his street-based practice, the Pop Shop was a continuation of Haring’s commitment to public engagement. The store sold merchandise for as little as 50 cents, featuring his distinctive motifs on T-shirts, badges, posters, making his art reachable to those who might never step into a museum. Every element of the Pop Shop was infused with Haring’s visual language and spirit. It blurred the boundary between art and commerce, not to exploit the market, but to subvert its exclusivity. The Pop Shop, like the subway drawings, embodied Haring’s belief that art should not be confined to elite institutions but should live among the people.

Haring extended this principle through high-profile collaborations with brands like Absolut Vodka and Lucky Strike cigarettes. His 1986 Absolut Haring lithograph, featuring his iconic cartoon figures encircling a vodka bottle, thereby challenging the distinction between street-level intervention and sanctioned marketing collateral. In 1987, Haring’s commission for Lucky Strike cigarettes further exemplified this trajectory, his graphic lexicon merging with the brand’s identity to interrogate themes of consumption, mortality, and the persuasive power of commercial imagery.

Banksy’s Brandalism

Ever the social commentator, a lot of Banksy’s art subverts advertising’s premises by co-opting familiar commercial tropes to critique social and economic inequities. His appropriation of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup series, recast with Tesco’s budget branding, seeks to comment on modern austerity and corporate dominance. By substituting Campbell’s packaging, Banksy transforms an icon of post-war affluence into a symbol of twenty-first-century frugality and inequality. In Very Little Helps, he depicts three children saluting a Tesco shopping bag hoisted as a flag, an unmistakable critique of the retail giant’s dominance over local retailers. By adapting Tesco’s own motto, “Every Little Helps,” Banksy underscores the irony of a corporation whose expansion has often come at the expense of independent communities. The work exemplifies his broader challenge to consumerism and corporate power, using familiar iconography to turn a supermarket emblem into a symbol of cultural conquest.

In his 2004 Napalm series, Banksy repurposed Nick Ut’s haunting photograph of a young Vietnamese girl fleeing a napalm attack, inserting the grinning figures of Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse at her side. This collision of childhood icons with a scene of profound trauma highlights the extent to which familiar corporate symbols can numb our emotional response to real human suffering. By portraying these mascots as unwitting companions in the aftermath of violence, Banksy asks viewers to confront the dissonance between the comfort of consumer culture and the brutal realities of war.

Banksy’s manifesto on advertising underpins his practice of "brandalism”:“Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head.” This declaration asserts that public space and imagery belong to the people, not corporations. Through “brandalism,” Banksy reclaims the visual landscape, urging viewers to question the omnipresent adverts that shape their perceptions.

Image © flickr / Comedian © Maurizio Cattelan 2019

Image © flickr / Comedian © Maurizio Cattelan 2019The 2025 Super Bowl and Cattelan’s Banana

In February 2025, Ray-Ban and Meta presented a Super Bowl commercial that encapsulates the integration of conceptual art within a marketing narrative. Set amid Kris Jenner’s private art collection, the advertisement features Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian: a banana fixed to a wall with duct tape. When Chris Pratt’s AI Meta Glasses identify the artwork and quote its $6.2 million valuation, Chris Hemsworth subsequently eats the banana, prompting a search to replace the piece. The use of Cattelan’s controversial piece underscores the tension between value ascribed by the art market and the everyday utility of objects, mirroring earlier Pop Art and street-art strategies of appropriation and viewer provocation.

By reabsorbing a work originally conceived as a critique of capitalist absurdity, the skit demonstrates how contemporary advertising repurposes conceptual critique for consumer engagement. The convergence of “high-art” iconography and product placement foregrounds the disposability of both objects and ideas within a commodified culture.

From Renaissance commissions to Banksy’s brandalism, artists have consistently appropriated advertising’s visual language to subvert its messages and expand art’s reach. However, in an age where marketing campaigns borrow from art and AI tools generate images indistinguishable from gallery work, the distinction between provocation and promotion becomes increasingly tenuous. Artists and advertisers both face the potential to operate within the same symbolic economy, trading in attention, emotion, and cultural capital.