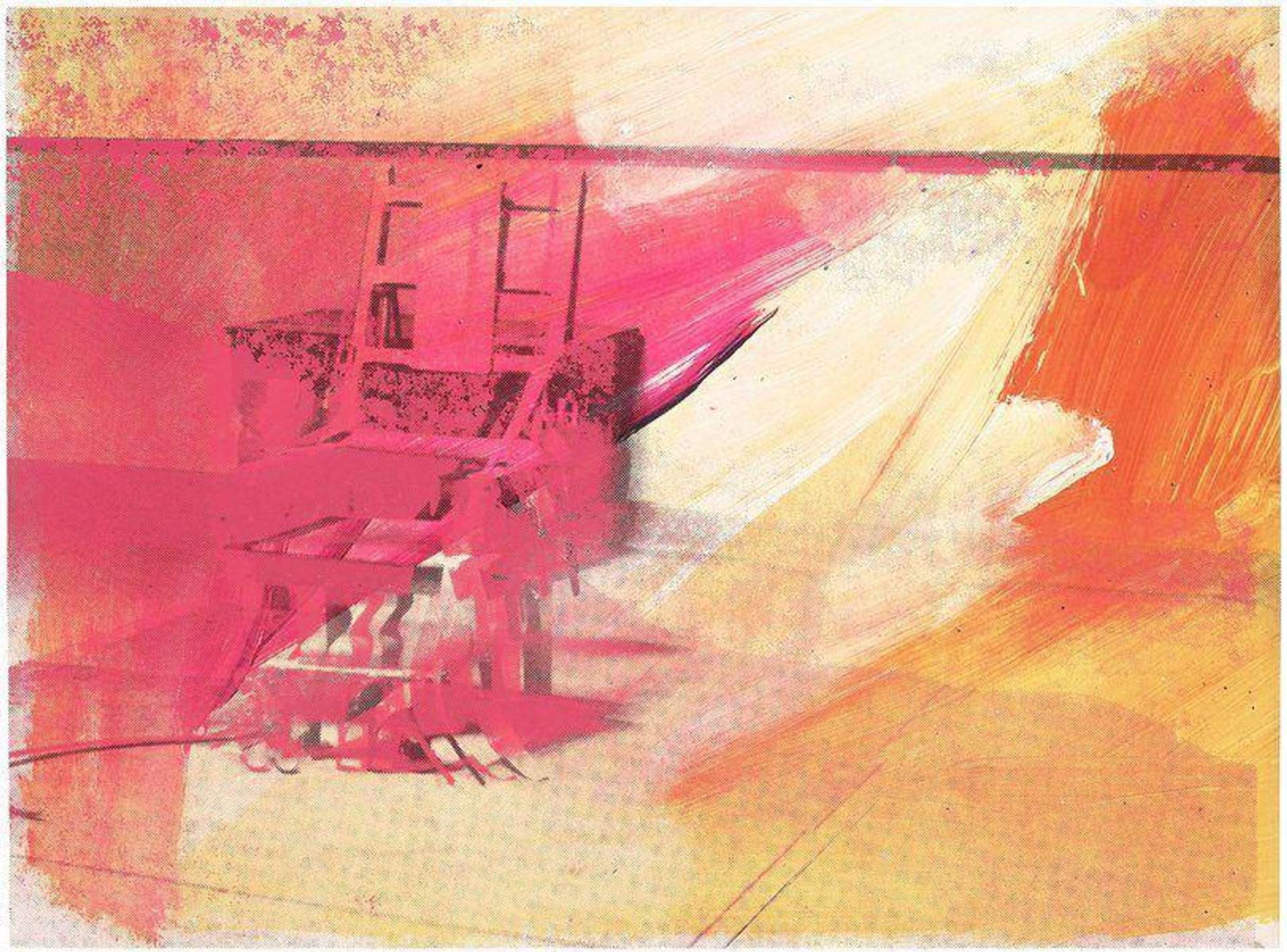

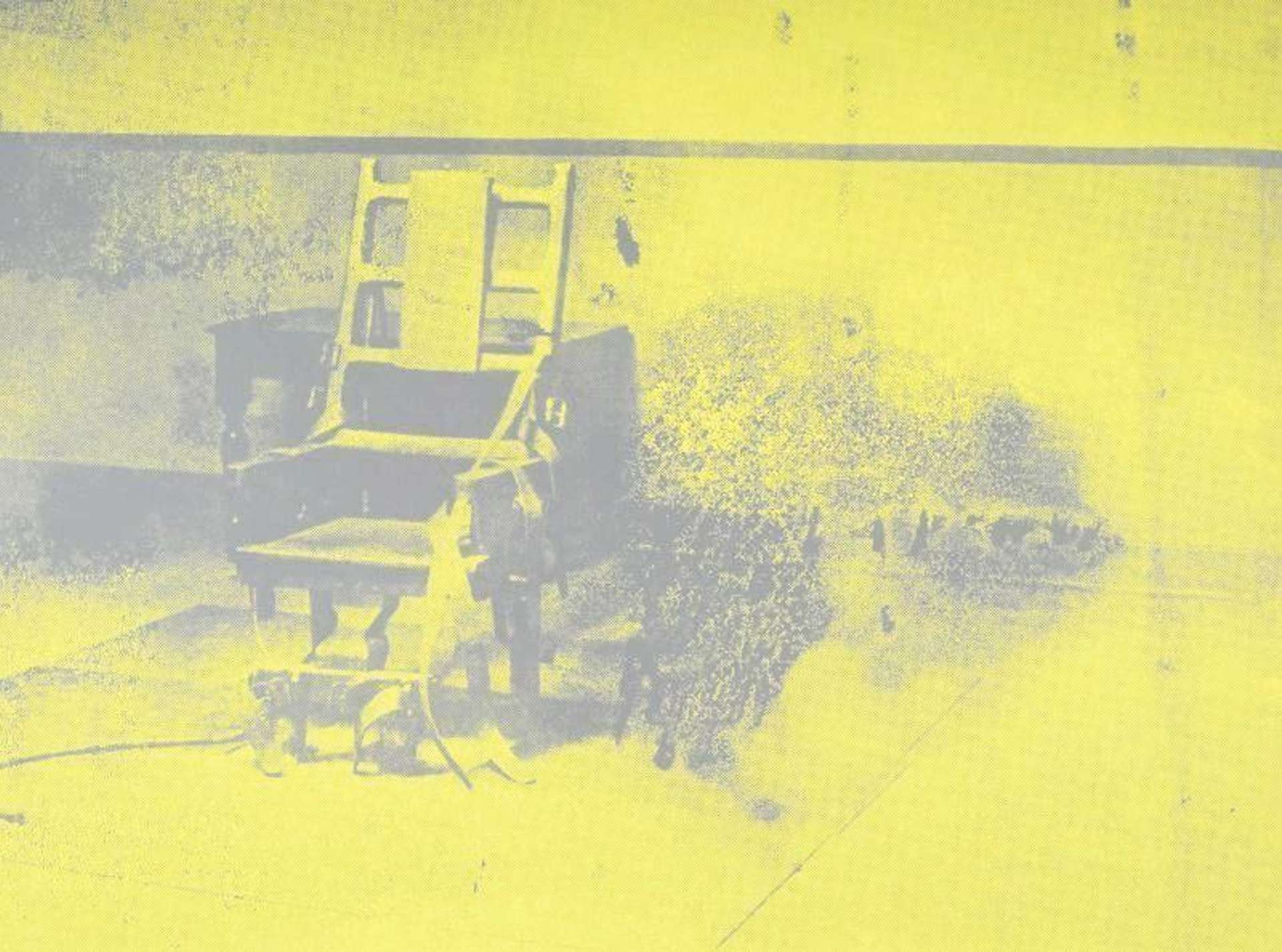

Electric Chair (F & S 11.80) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F & S 11.80) © Andy Warhol 1971

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

Read Chapter Five of our exclusive mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter 5

On a sunny afternoon in Maui, in 2009, Alice Cooper was playing golf with his buddy Dennis Hopper. While lining up a putt, Dennis casually mentioned he owned several Andy Warhol paintings, and had just sold his Mao print for a lot of money. However, it wasn’t just any Mao print. During the 1970s, Dennis returned home one night in a drug-fueled rage and found himself staring at his Mao silkscreen. Spooked by the Chairman’s ominous gaze, he pulled out a revolver and shot two holes it. He showed it to Andy Warhol, who circled the bullet holes and annotated them — effectively turning it into a Warhol/Hopper collaboration. Apparently the art market approved because someone paid US$300,000 at Christie’s for the print (a Mao — sans bullet holes — was worth US$35,000).

Upon hearing the story, Alice mentioned he had a Warhol — somewhere. As Hopper put it, “Well, you better find it!”

That’s when Alice put in a call to his mother, who was ensconced in his Scottsdale home. He asked his mom to go to the garage and look for a cardboard shipping tube that had a sheet of red canvas rolled up inside. It took her awhile but she eventually found it. As soon as Alice heard the good news, he asked Dennis for advice on how to sell it. Dennis suggested he call Tony Shafrazi, the New York dealer who represented his photography. Shafrazi’s response was that Alice needed to show the painting to the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board to have it authenticated. But then he couldn’t resist adding a little zinger, “It’ll probably be a waste of time because they’re a bunch of jerks (only he used an expletive instead of jerks).”

Image © Christie's / Mao (F & S 11.99) © Andy Warhol 1972

Image © Christie's / Mao (F & S 11.99) © Andy Warhol 1972Tony Shafrazi knew Warhol’s work well, having mounted an impressive show of commissioned portraits. A book, titled Andy Warhol Portraits, accompanied the exhibition and featured a striking painting of Debbie Harry with lavender hair and cherry red lips, on the cover. However, Shafrazi had a checkered past. He was once the Shah of Iran’s art dealer during his quest to build a contemporary art museum. Shafrazi was also once arrested for spray painting graffiti on Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica, while it hung at the Museum of Modern Art. During the 1980s, in a “dazzling act of chutzpah” (to quote the critic Robert Hughes), he reinvented himself as a graffiti art dealer. Shafrazi gave Keith Haring his first solo show and hosted an exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol’s collaborative paintings.

Perhaps Alice was discouraged by Tony Shafrazi’s lack of confidence in the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. Or maybe he was simply too busy touring. Whatever the reason, Alice never got around to authenticating the painting.

Image © Christie's / Outlays Hisssssssss (Collaboration #22) © Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat 1984

Image © Christie's / Outlays Hisssssssss (Collaboration #22) © Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat 1984Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board's Controversial History

When Andy Warhol died, in 1987, the estate took its time before establishing an art authentication committee. Initially, they handed the responsibility to Fred Hughes, Andy’s long-time business manager. Hughes received occasional back-up from Vincent Fremont, Warhol’s office manager. However, they soon became overwhelmed with applicants, and decided to set up an official art authentication board.

Assembling an art authentication committee is common practice when a historical figure leaves behind a substantial estate. Most estates — from Picasso to Pollock — eventually establish art authentication boards. Members are usually composed of dealers, artists, museum curators, and art historians. But just as often family members play a prominent role — which can be a mixed blessing. While relatives are often well-meaning, in most cases they are simply not knowledgeable enough to render a competent opinion.

For example, when Jean-Michel Basquiat passed away, his father, Gerard Basquiat, installed himself as the head of the authentication board for his son’s work. Gerard (who died in 2013), was a sophisticated person, who worked as an accountant, and owned a brownstone in Brooklyn. Yet, multiple accounts emerged that he let his personal feelings toward an individual influence his decision. Despite having a board composed of true experts, Gerard ultimately dismissed everyone, deciding he could do a better job himself. That supposition, of course, was highly debatable.

The Difficulty of Authenticating Warhol's Art

Andy Warhol authentication is complicated. That’s because Andy used a photomechanical process to create his paintings — which is easily duplicated by someone with basic knowledge of the technique. This, coupled with the shenanigans which went on during the early days of the Factory, led to a large number of bogus Warhols on the market. To make matters even more complicated, the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board established a set of criteria for approving paintings that seemed to ignore the experimental nature of Andy’s work.

Although this story has been told ad nauseum, it still bears repeating that the Warhol board was sued by the collector Joe Simon, over a red Self-Portrait from 1965 (that was part of a group of seven similar paintings). Despite the fact that Joe’s painting was originally authenticated by Fred Hughes, it was rejected. The board ruled against Simon’s canvas because they determined it was done “off premises.” What had happened was that Andy made a trade with a magazine publisher named Richard Ekstract for the six-month use of a newfangled device called a “video camera.” Warhol, who was known to be frugal when he wasn’t being paid in cash, decided to save time and money by jobbing out the fabrication of the pictures. He phoned a silkscreen shop that he previously worked with and furnished them with the original acetate. Upson their completion, he gave the finished paintings his personal approval. What the Warhol board seemingly failed to take into account was that Andy functioned like an art director; his paintings involved a collaborative process. What’s relevant here is that Richard Ekstract’s cache was created under Warhol’s auspices, via a team effort. The bottom line was that it all came down to intent on the part of the artist. Andy intended Joe Simon’s painting to be one of his creations.

When Joe Simon’s painting was stamped “DENIED” on the back, in red indelible ink, he brought a lawsuit against the board. Even though they ultimately prevailed, because they could afford the finest legal services in New York, they decided to get out of the authentication business. This created an opportunity for me to fill the yawning niche they left. While the approval of the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board remained the gold standard, the credibility of my art authentication service continued to grow over time. If you consistently do good work, and treat people fairly, you develop respect within the industry.

However, that doesn’t mean clients don’t try to deceive you. They often fabricate elaborate backstories about their pictures. Usually, the more complicated the story, the less likely the picture is genuine. Owners often equate an overabundance of details with an object being real. It’s analogous to galleries which issue extravagant fake certificates of authenticity covered in embossed gold seals and fancy borders.

Image © trevor.patt / Self Portrait (Fright Wig) © Andy Warhol 1986

Image © trevor.patt / Self Portrait (Fright Wig) © Andy Warhol 1986Acquiring Provenance

Andy Warhol provenances are relatively easy to confirm because his exhibition history has been well-documented. The problems creep in when painting were given as gifts, received in trades, or stolen (just because a crime is committed doesn’t mean a picture isn’t authentic). Since there was rarely any paperwork associated with these transactions, I had to rely on my knowledge of how the Factory operated.

Despite obstacles with determining an accurate provenance, the first step in authenticating a work of art is analyzing its visual qualities. Art authentication is based on two things; what does an object look like and what is its backstory. Of the two issues, the most important is what does the object look like. If it doesn’t check out, then the picture’s provenance becomes irrelevant. When I am hired to examine an Andy Warhol, the first thing I do is determine how it relates to other Warhols known to be genuine. Usually, I have a pretty good idea whether the work is authentic when I first see it. However, rule number one of the art authentication business is to never assume anything. This is why I take each painting through a specific process.

Looking for a Buyer: Early Hopes & Early Disappointments

Once Alice and Shep received my authentication report, confirming the work’s authenticity, they decided they wanted to sell the Warhol. I sensed Alice enjoyed the idea of owning the painting more than his actual desire to live with it.

At that point, I mentioned to Shep that he might want to offer the painting to Peter Brant — who owned twelve Little Electric Chair paintings — making him effectively the world’s largest owner of works from this series. I also informed Shep that I had access to Mr. Brant, having appeared as an expert witness on his behalf, during a court case involving the disputed ownership of the Warhol painting, Red Elvis (a case which we won). Shep suggested I contact him to gauge his interest in the painting.

I reached Peter at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut and cut to the chase, “Hi Peter, it’s Richard Polsky. I recently authenticated Alice Cooper’s red Little Electric Chair — it’s one of the best I’ve seen — and was wondering if you might be interested in taking a look at it?”

“Yeah, I just heard something about it — I forgot where. You know, I’d love to see the painting in person but I had an accident and can’t leave the house.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“I was playing polo last weekend and fell off my pony — so now I’m stuck in bed for two weeks.”

I recalled the time I visited Peter’s compound in Greenwich, which included a polo field — not something you see everyday, even in the world of ultra-wealthy art collectors. Thinking fast, I responded, “The painting’s at Crozier’s. What if I could arrange to have it brought to you so you can take a look at it in your home?”

“You would do that for me?”

Smiling slightly, I said, “For you, Peter? Of course I would.”

I got back to Shep and he agreed to foot the bill to have a courier service ferry the painting to Greenwich. Peter viewed the picture the next morning — but I heard nothing from him. I even spoke with the courier service to see if they got a reaction — but they were of no help. I decided to give it another day and then called him, “Peter, how are you feeling?”

“Better — much better.”

“So, what did you think of the painting?”

“It’s a good one.”

“Are you interested?”

“I don’t think so,” he said. “I already own a dozen — that’s probably enough.”

And that was that.

Tentative next steps: Andy Warhol Museum & Bonhams

In retrospect, Peter was probably bored and thought it would be fun to see how Alice’s painting compared to his holdings. As one of the top ten art collectors in the world, he was used to having dealers and auction houses accommodate him.

After informing Shep that Peter turned down the painting, we began to discuss the difficulties of marketing the Little Electric Chair, created by its exclusion in the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné. As we strategised, Shep had a thought. It turned out that he knew one of the trustees at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Shep’s stratagem was to have the museum exhibit the painting, thereby conferring legitimacy. He even offered to bring in Alice to do a lecture on Warhol and how he came to acquire the painting. In a nutshell, it was a stroke of brilliance where all parties benefited.

The Andy Warhol Museum tentatively agreed to the proposal. In the meantime, I contacted Laura King Pfaff, a colleague and chairman emeritus of Bonhams auction house — a top five player which had been around for over 200 years. Bonhams was known primarily for its sales of classic motor cars and rare wines, but it also had a substantial contemporary art department.

I hadn’t spoken to Laura in years. But she instantly grasped the possibilities when I mentioned the availability of Alice Cooper’s picture and how it might be exhibited at the Warhol Museum. She immediately proposed that Bonhams handle its sale. She also proposed a major marketing campaign to promote the painting: a thirty-page catalog, a tour of key art world capitals like London and Hong Kong, and most impressive of all, a full-page color ad in The New York Times. Later that day, Laura called back and suggested a pre-sale estimate for the painting of US$5-7 million.

I conveyed to Shep the terms Bonhams offered; he was duly impressed. But then the deal with the Warhol Museum began to unravel. In retrospect, the museum trustee’s offer had been premature. He never checked with their chief curator, who had other ideas. Essentially, they were concerned about being used to authenticate the painting by hanging it — while going out of their way to say they never doubted its authenticity.

Now I had to face Laura King Pfaff and finesse the reason why the Warhol Museum show had fallen apart. I calmly explained that exhibiting Alice’s Little Electric Chair had grown too complicated — a case of the trustees and curatorial staff not being on the same page — which was the truth. Laura, while disappointed, was satisfied with the explanation. She said, “We’re still interested. But now you’re looking at a more modest estimate.” Even at a lower figure, we decided to move forward with Bonhams, confident the painting would find a buyer and bring a good price.

Contracts were signed. Only a week later, Alice Cooper appeared on a live NBC broadcast of Jesus Christ Superstar. John Legend played Jesus, with Alice performing as King Herod. Though Alice was only in one number, he stole the show. Between the release of the best-selling Paranormal, the publicity from the discovery of his Andy Warhol painting, and his television appearance in Jesus Christ Superstar, Alice seemed to be everywhere. Our timing was perfect.

Though we had a signed contract with Bonhams to auction Alice’s painting, they remained jittery. I had a conversation with their director of Post-War and Contemporary Art. As we talked, he revealed how he was spooked by a previous unexpected event.

The director explained, “We need to be extra-careful about selling any Warhol that doesn’t appear in the catalogue raisonné. Not long ago, we agreed to sell a major painting by another artist and ran into potential liability issues.”

“Who was the artist?”

“I’d rather not say,” he said.

I did a little research and discovered it was a Basquiat canvas. Bonhams had consigned the painting and even put it on the cover of their monthly magazine. It turned out that they weren’t aware that the Authentication Committee of the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat once rejected it. Just prior to the sale, they learned the truth and immediately withdrew the painting. You can appreciate the embarrassment it must have caused.

I realised I needed to buttress Bonhams confidence by providing them with even more history about the Little Electric Chair. In a perfect world, Alice Cooper would have kept better track of his treasure. He would have had Andy sign it and maybe even documented the process. A photograph of the two of them posed with the canvas would have gone a long way toward establishing its bona fides — and saved much future grief. Regardless, everything checked out. The picture was 100% genuine and it was a beauty. Still, when I hung up the phone with Jeremy, I detected a whiff of doubt.

Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol'.

Read the previous instalment of the series here.