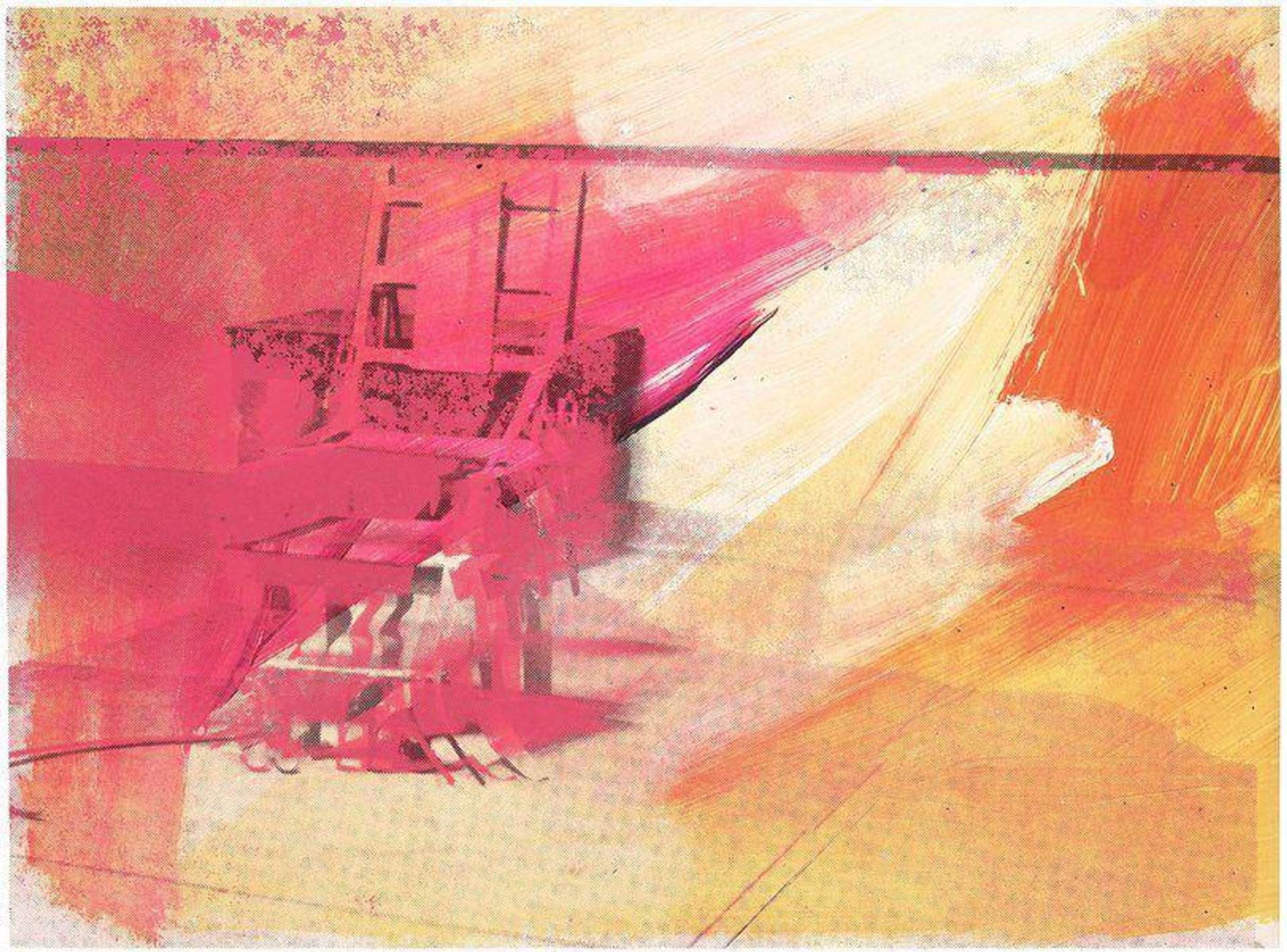

I Authenticated Andy Warhol: The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Electric Chair (F & S 11.76) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F & S 11.76) © Andy Warhol 1971

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

Read Chapter Six of Richard Polsky’s mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter 6

Bonhams’s Director of Post-War and Contemporary Art reflected on his current situation. He was finally in a position to offer a multi-million dollar Andy Warhol painting to his clients. While Bonhams was certainly a respected auction house, he knew these treasures always seemed to wind up with the big boys like Sotheby’s and Christie’s. And who could blame a consignor for not going with the sure thing. But now, at long last, the gods had smiled upon him; he had the goods.

One of his first calls was to Alberto Mugrabi, a member of the art dealing family collectively known as the “Mugrabis.” Given they own hundreds of Warhols, they exerted a fair amount of influence over the Warhol market. They also bid freely at auction, furthering their standing. With that in mind, the director placed his call, filled with anticipation.

Rather than a warm reception from Alberto Mugrabi, he was met with scorn. Or, to be more exact, Alberto was immediately suspicious of why Bonhams — and not Sotheby’s or Christie’s — was given the task of selling Alice Cooper’s painting. Apparently, he said something to the effect of, “How good can it be if Bonhams has it?”

While I wasn’t privy to the conversation, the Bonhams director had plenty of potential rebuttals. He could have cited my relationship with Laura King Pfaff. Or he simply could have said they made the consignor a pre-emptive offer filled with incentives. Whatever went down during the conversation, it didn’t go well; Alberto Mugrabi wasn’t interested.

The director was completely deflated by this unexpected turn of events. For no apparent reason, other than the perceived lack of prestige, his opening salvo went nowhere. There was always a chance the Mugrabi family was planning to bid on the painting and tried to dampen interest in it. Whatever the case, Bonhams was spooked by the response, and probably imagined the worst case scenario; What if no one wanted to buy Alice’s painting?

When the director called me, I hadn’t been brought up to speed with what just happened.

“Hey, how’s it going?” I asked.

“I just got off the phone with a major collector — who expressed zero interest in the painting.”

I was stunned and quickly asked, “It wasn’t the Mugrabis, was it?”

The director hesitated, then confessed, “Yes it was.”

“What did they say?”

“Well, I can’t go into all of the details, but they had serious doubts about the picture,” he said, his voice heating up.

I became a bit defensive, “What are you talking about? The quality of the painting? Its authenticity? The pre-sale estimate?”

“Everything,” he replied.

From there, the discussion went downhill rapidly.

The Bonhams director — possibly under instructions from his superiors — began to nitpick the details of the timeline we created about the history of the painting. Basically, he seized on a few minor technicalities. It felt like he was probing to find a way to get out of the deal. As the discussion continued, it became obvious to me that Bonhams had lost confidence. It made me wonder who else they offered the painting to. Though I realised we had a binding contract, I knew Shep wouldn’t waste his time with a lawsuit. Even assuming we’d prevail, it wouldn’t have been worth disrupting his life.

When I got off the phone with Bonhams, I was stunned. It took me a few moments to collect my thoughts and call Shep. He listened carefully, interjected once or twice, and finally said, “There’s no point having someone sell something if they don’t believe in it.”

I knew he was right. Yet, not only was I upset that I was no longer going to receive a taste of the deal, I was livid that a painting I had authenticated was being questioned. It didn’t sit well with me that Bonhams signed a contract — and was being let off the hook. Especially after all of the time I spent putting them together with Shep and Alice. This was exactly what was wrong with the art business; there was no accountability.

Then an unexpected opportunity arose; the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame came calling. They had gotten wind of the painting and approached Shep to ask if he would consider allowing them to display it for a year as part of a special Alice Cooper installation. Shep was particularly close to the Hall’s director and was inclined to grant him the favour. On a hot and humid summer afternoon in Cleveland, the Hall hosted a reception to unveil the painting. They even displayed a vintage Alice Cooper pinball machine next to the canvas and the original electric chair stage prop from the 1970s.

Alice and Shep flew in for the event. They kindly invited me, but I sent my eighty-seven year-old mother Marlit — who lived in Cleveland and was an Alice Cooper fan — as my emissary. She told me, “When I introduced myself to Alice as Richard Polsky’s mother, all of a sudden his eyes grew wide!” That evening, my mother proudly emailed me a picture of her with her arm around a grinning Alice.

Baldwin's desired painting was similar to others by Ross Bleckner in its bokeh-like haziness. (Image © Instagram @rossbleckner)

Baldwin's desired painting was similar to others by Ross Bleckner in its bokeh-like haziness. (Image © Instagram @rossbleckner)The need for authenticity in a world of scandal

While Alice’s painting hung at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, my art authentication business began to mirror the growth of the art market. As prices rose, so too did the incentive to produce fakes and forgeries. Scandal after scandal hit the papers. One of the more high-profile incidents was the Mary Boone/Alec Baldwin controversy. The story’s origin lay in the actor’s interest in the work of Ross Bleckner. During the 1980s, Bleckner emerged as one of the best known painters in Mary Boone’s famous stable, taking his place alongside David Salle, Julian Schnabel, and Eric Fischl. While Bleckner never achieved their status or prices, he still became a big seller.

One day, the actor Alec Baldwin wandered into the Mary Boone Gallery and was struck by a large painting by Bleckner titled, Sea and Mirror — that he had to have. Alec was a big Ross Bleckner fan and had developed a personal friendship with the artist. As for the painting, Boone was in the enviable position of saying it had already been sold (if there’s one thing that gets an art dealer’s pulse racing it’s being able to deny a client). However, Baldwin was used to getting what he wanted.

In an impressive bit of salesmanship, Mary Boone suggested she call the owner of the canvas and see if he’d consider selling — at a profit. The work in question was priced at US$190,000. Baldwin liked the idea — a lot — and told Mary to see what she could do. Sure enough, Alec soon received a call from Mary saying she had worked her magic. The owner of the Bleckner was willing to part with it for a US$50,000 profit. Baldwin agreed to the price and Boone said she’d make the appropriate arrangements.

Not long after, an art shipping truck pulled up to Alec Baldwin’s New York apartment. The large painting, which resembled a cluster of multi-colored sea anemones, was installed at the end of a long hallway. Alec stood back to admire his new acquisition. It was good to be a star and always get what you want. Yet, over the course of the next few days, something nagged at him. The painting looked slightly different than the one he thought he had purchased; the paint looked new. Alec called Mary Boone and expressed his concerns. Mary countered by explaining how she generously had the painting cleaned since “it had come from the home of a heavy smoker” — that’s why it looked so fresh.

Years passed. Somehow, the painting came up in a conversation with friends, and Alec mentioned that something just didn’t seem right about it. When Alec expressed that perhaps it was because the painting had been cleaned, one of his friends said it sounded fishy. Alec went home, took a closer look, and realised it wasn’t the same painting he thought he had bought.

An angry call was placed to Mary Boone. Alec demanded to know what was going on. Allegedly, Mary insisted the painting was the same one Alec thought he had purchased. Still not satisfied, Alec called Ross Bleckner to get his take on it. When he reached Ross at his Hamptons studio, he confessed that he had painted a replica of the original. He also apologised profusely. But at the end of the day the fact remained that Alec Baldwin had bought a copy. While you couldn’t quite call it a fake — because it was a genuine Bleckner — he had been scammed.

Alec Baldwin filed a lawsuit against Mary Boone. On her attorney’s advice, Boone decided to settle out of court, with Baldwin receiving a Bleckner painting and an alleged seven-figure payout. Bleckner’s complicity in the deal was never made clear. The press pointed out that he and Baldwin managed to patch things up. As for Mary Boone, she soon got into some unrelated trouble for tax evasion, and wound up serving prison time.

A few years later, Alec Baldwin, while on a movie set in Santa Fe during the filming of “Rust,” was involved in an accidental fatal shooting. The outcome, as to who was responsible, has not been resolved as of this writing.

The growth of the gallery giants

Meanwhile, the art market was undergoing an unprecedented period of expansion. Financial advisors began recommending that high-net-worth individuals include blue-chip fine art in their portfolios. The auction houses, in a desperate bid to attract expensive property, offered guarantees to consignors — which in effect meant the painting was sold before the auction even began. The top galleries embarked on a new strategy which can be summed up in a single word; expansion. Pace, Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, and David Zwirner opened multiple exhibition spaces around the globe. Gagosian started his own magazine. Hauser & Wirth went one better by not only publishing their own magazine, but opening a restaurant at their Los Angeles outpost. Buying and selling art had never been more popular — and more lucrative.

Another arena of growth was art fairs. Back in 1978, when I started out in the art business, there were exactly two serious art fairs; Art Chicago and Art Basel (Switzerland). Now there are hundreds, if you include all of the smaller satellite fairs which hover around the major global events. Exhibiting at an art fair is a major commitment of time and money. The bigger galleries can easily spend US$100,000 or more, citing booth costs, travel, and staffing. Yet, despite the high cost of participation, there always seems to be a waiting list to get into the most important events.

Art fairs have become a curious phenomenon. It used to be that a gallery would spend a year preparing for one. They would hold back choice works from their secondary market inventory until the fair, hoping to impress collectors and colleagues alike. If you represented an artist, you would put aside select pieces, rather than rush out and make a quick sale. You might even decide to part with a great painting from your own personal collection in hope of assembling a booth that would blow away your competition.

Now, the leading galleries go to their artists and place orders, as if they were contracting with a factory. A typical request from a dealer to his artist might go like this: “We’re doing four art fairs this year. I need you to make two paintings for Basel Miami, one for Art Chicago, a bunch of prints for Fog San Francisco, and another three paintings for FIAC in Paris.” Obviously, making great art requires introspection; you can’t rush it. Any artist who agrees to streamline the creative process, to accommodate a dealer’s needs, is asking for trouble.

The realities of art collecting

During the 1980s, art fairs would host an opening reception, which a collector might pay US$150 to attend — with the money going to charity. Attending the vernissage also gave you first dibs on the art that was for sale. Savvy collectors happily took advantage of the situation to snap up the best paintings before the general public got a shot at them. Dealers, looking to save money (never underestimate the cheapness of an art dealer), soon began forging opening night passes so they could attend the previews for free. Eventually, the fair organisers caught on and printed tickets which were hard to counterfeit.

But at least the works at the opening night party were actually for sale. Currently, dealers tend to pre-sell what they intend to bring to a fair to their best clients. Emails are sent out offering the collector a chance to buy what’s already been earmarked for the gallery’s booth. A client makes their purchase, often without seeing it, and then the piece is transported to its art fair destination and hung in the booth — usually without a red dot. That way, the dealer has the pleasure of telling anyone who inquires, “The piece is sold.”

Perhaps the funniest thing about art fairs is how dealers brag relentlessly to the press about all of their success. If you can believe them, they go from triumph to triumph. The press is always happy to cooperate with this charade, knowing they have a story to write. Personally, I don’t think I’ve ever heard a dealer not claim to have a big opening night. My favourite comment is when a dealer gushes, “I’ve already had to re-hang my booth — everything’s sold!” The truth of the matter is if a dealer tells you they had a “great fair,” that means they made a slight profit. If a dealer tells you they met lots of new collectors and museum curators, that means they broke even. And if a dealer tells you the fair has incredible potential, that means they lost money.

Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol.'

Read the previous instalment of the series here.

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com