Courtesy of Richard Polsky

Courtesy of Richard Polsky

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

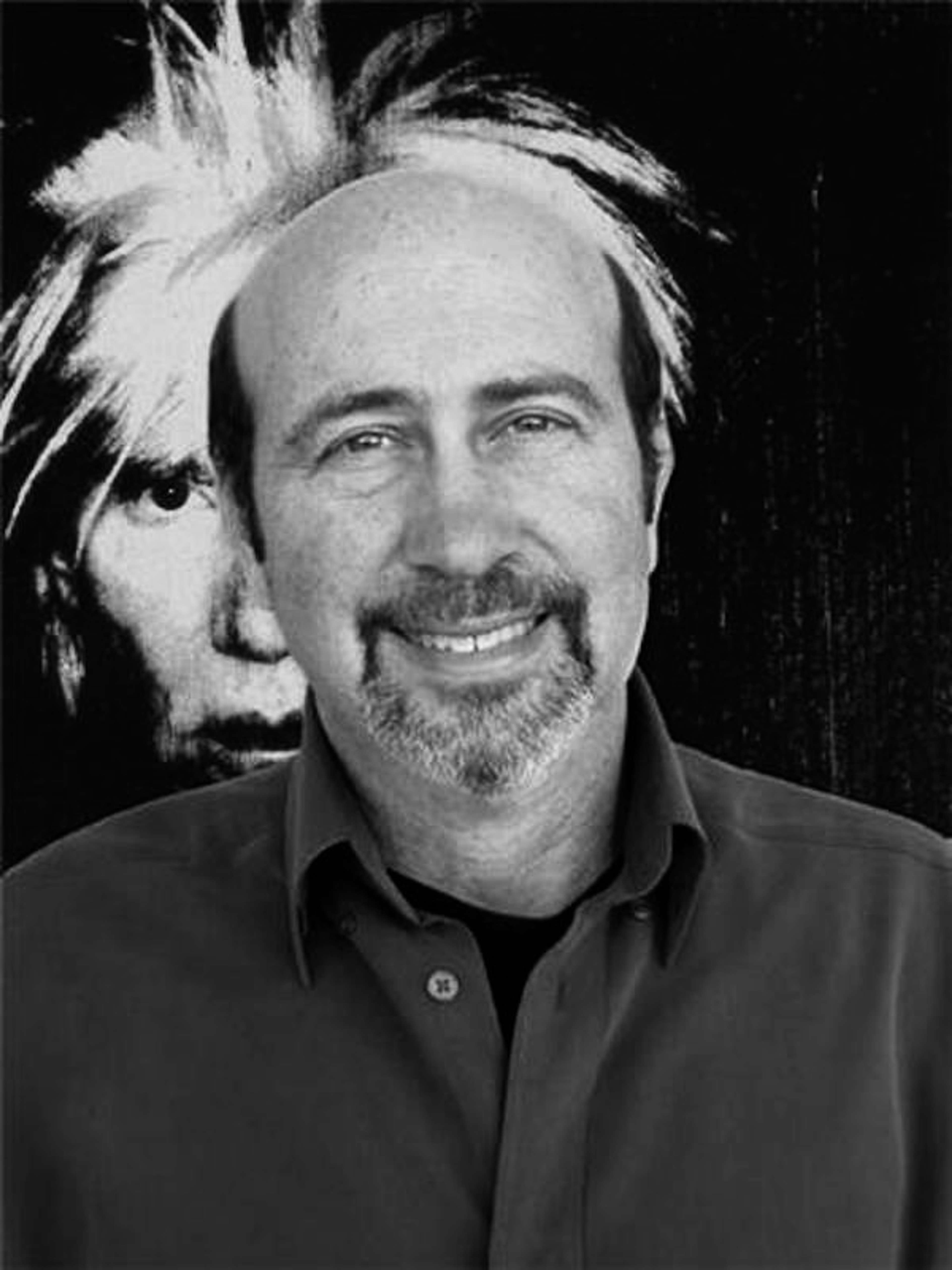

Richard Polsky is a leading expert in the Andy Warhol market. With an illustrious career behind him as an art dealer in the 1980s in the US, and now running an art authentication business, Richard is one of the few people in the world who can spot a fake Warhol print upon first glance.

Here he chats with our Managing Director, Charlotte Stewart, about why Warhol prints stand the test of time and reveals his thoughts on what he calls the shift ‘from the artworld to the art market’ over the last 40 years.

Charlotte Stewart: Richard, you’ve had a legendary career in the Warhol market, where and when did you start?

Richard Polsky: I started out in the artworld back in 1978 when I was 23. I moved from Cleveland, Ohio to San Francisco and I came out there with the idea of making art. I wanted to be an artist! But once I ended up working for a gallery I discovered that I was a way better dealer than artist.

After a while working for a gallery, I had enough money to open my own space. Art in the 1980s was the first boom market and you could make a really interesting living selling artworks back then. People now talk about what happened post-2008, but if you go back further you wouldn’t believe how exciting it was during that time. The whole thing crashed in the early 90s however, when the real estate market went south. It was a disaster! At that point I ended up becoming a private dealer and briefly moved to New York City, but it was a difficult business.

Polsky and Warhol in Warhol's studio, 1986. (1986 © Richard Polsky)

Polsky and Warhol in Warhol's studio, 1986. (1986 © Richard Polsky)CS: How did you move from galleries and dealing to authentication?

RP: Years later, I turned 60 and realised - I have to make a living somehow! I thought I better get serious, because the art market was falling apart for dealers like myself.

As I said, there was the big shift in the post-2008 market, where art became one of the ultimate investments. In order to invest in art now, you have to have millions of dollars. In other words, the key to the art business is being able to control your own inventory. You have to own things and you have to be a collector.

I used to deal with and show the work of artists like Ed Ruscha. Things I’d buy for $5-10,000 were suddenly 10 times that in the post-2008 market - and now they’re maybe 100 times that - it’s crazy! Basically, I was priced out of the business at this point because I couldn’t buy inventory.

What’s that old saying… ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’? Well, I was literally sitting in an old cowboy bar one day, having a beer, and asked myself: ‘what’s the biggest problem in the art market today?’ What hit me was that no one could get their paintings authenticated.

CS: How did you come to this realisation?

RP: In 2011-2012, the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board went out of business.

The turning point was with the US-born filmmaker and player in the British art-world, Joe Simon. He had a particularly hard time with the Warhol authentication board back in 2001 after he’d found a buyer for his Warhol painting bought in 1989, who had agreed to pay $2 million for it. It was a red silkscreened, 20 by 16 inch self-portrait from 1965.

The painting had a stamp on the back from Fred Hughes, Andy Warhol’s executor and late chairman of the Andy Warhol Foundation, to certify that it was authentic. Shortly after this period however, Hughes was so overwhelmed with the Warhol estate that he started an authentication committee and abstained. This new committee was suddenly inundated with applicants for authentication, largely because of Warhol’s silkscreen technique; they’re pretty easy to forge - even I could tell you how to do it!

So the Warhol people did something very interesting. If you brought them a painting you had to sign a document agreeing to allow them to stamp the back of it with: ‘DENIED’, if what you brought in was a fake. If this happened, you were pretty much screwed and there was no way you could resell it. People agreed to do this because there was no other choice at the time. This is what happened with Joe Simon.

The buyer of Simon’s painting understandably wanted the Warhol board to carry out an authentication check, before spending $2 million on the work. Joe said yes. But they turned it down, and all hell broke loose. The reason the Warhol board turned it down - they didn’t tell Joe this, but I found out - was that they claimed it was created off premises and not at the studio.

It turns out Simon’s portrait was made as part of a deal in 1965 between Warhol and, the then, young magazine publisher Richard Ekstract, in exchange for one of the world’s first video cameras. As part of this deal, Warhol gifted Ekstract seven self-portraits for him and his employees.

Andy was notoriously cheap, where if he didn’t get money for a deal, he’d sometimes send the image he wanted silkscreened to a downtown silkscreen studio. This isn’t an isolated incident. Andy’s work was experimental by nature, he was a collaborator, and many of his silk screens were done with other people. But because they were made off-premises, the Warhol board declared them as fakes!

Joe Simon thought this was absurd. Fred Hughes had approved his work for goodness sake! But the board wouldn’t back down. Long story short and $7 million later, after legal battles between Simon’s and the Warhol board’s lawyers, the board decided that they’d had enough of authenticating work - people just got too upset! There was a domino effect here: the boards for Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Roy Lichtenstein, Isamu Noguchi, Pollock - they all abdicated.

So when I’m drinking that beer in the old cowboy bar…it occurred to be - I know quite a lot about Warhol! I’ve written two books, I’ve shown his work, I’ve dealt with the estate and I have the connections… I should do this! One thing led to another, it was a lot of work and over time I became involved with Haring, Basquiat, and Lichtenstein.

CS: What do you do when you see one of these “blacklisted” Warhol’s?

Well, it’s a real problem. Anyone who hires me, all they care about is being able to sell the painting. Nobody keeps it. Most of what I look at is not genuine, but sometimes you do see things that have fallen between the cracks.

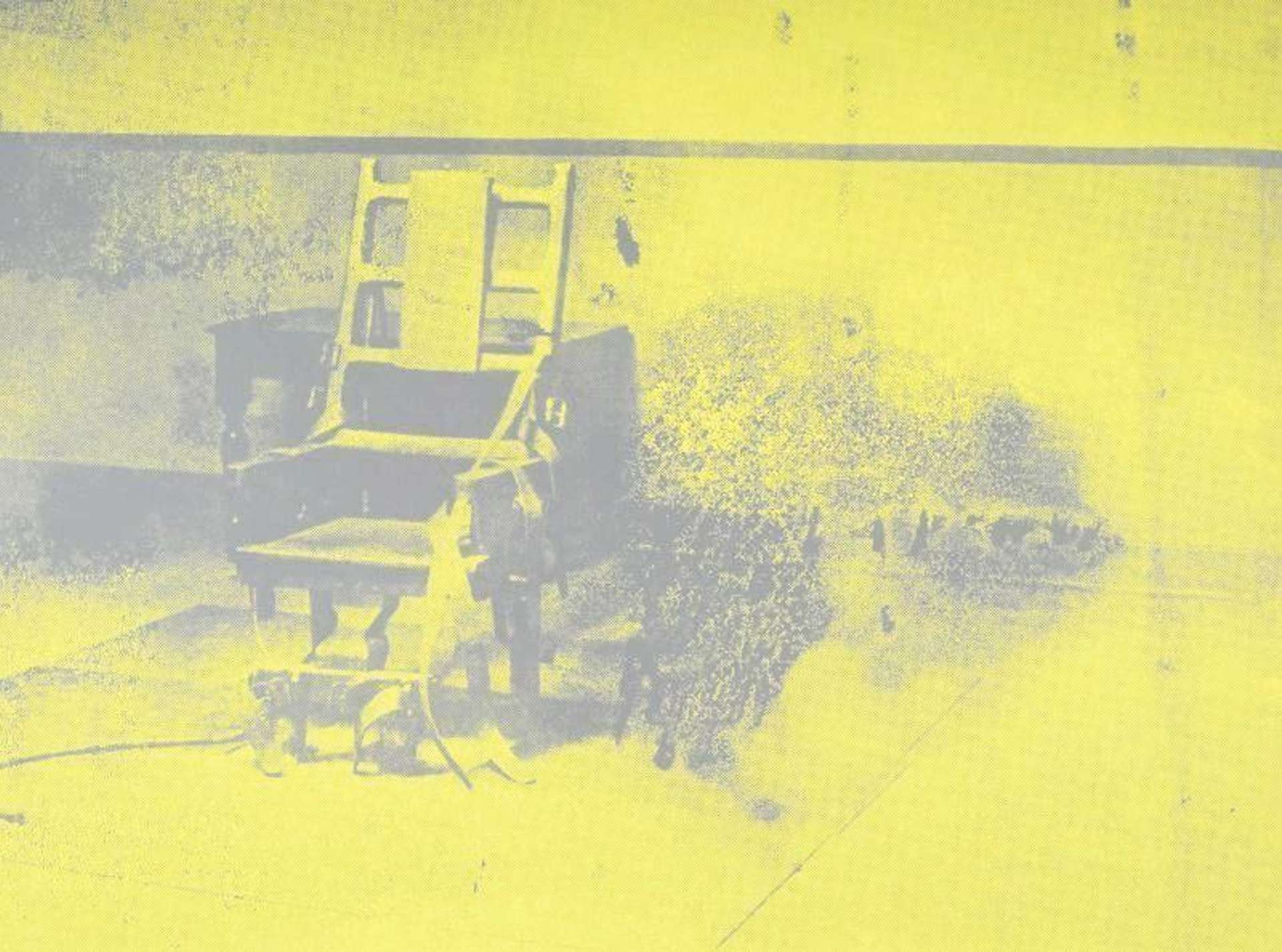

On my website there’s a small group of paintings that I’ve authenticated and have turned out to be real. There’s a Marlon Brando portrait that I authenticated, a couple of Soup Cans, some Electric Chairs, including a red one that belonged to the rock star Alice Cooper. There are all sorts of adventures for paintings out there. But if a painting is denied by the board, and the Warhol people were pretty good, it’s usually denied for a good reason. There are fakes in the Catalogue Raisonne.

That’s the thing about Catalogue Raisonnes, they are almost impossible to finish and get 100% perfect. But the Warhol people, by and large, did a good job. Yet, they even turned down a painting that belonged to Ivan Karp - the guy who discovered Warhol and brought him to the attention of Leo Castelli!

CS: With all this first hand experience with Warhol paintings over the course of your career, you must have developed a certain sense when you see something where alarm bells start ringing. Can you take us through some of these alarm bells that come up?

RP: Authentication is based on two things: What does the object look like? And what is its backstory and its provenance? The most important thing is what it looks like. So if I see a painting, and I’ve been around for 40 years, and it doesn’t look right then I don’t even care what the backstory is, it has to visually align with other paintings that are known to be genuine.

A painting has a personality. Just like a person. There’s charisma in every painting, or a lack of one, and you just kinda know the real deal when you see it. Like I said, I’ve seen ones that are close that could go either way. Then you dig a little deeper into provenance and somebody tells me some unbelievable story. I always ask: ‘show me something, prove it!’ But people rarely have the goods. A genuine painting usually has a provenance that can be traced accurately or at least makes some sense to me.

With Basquiat, you hear the craziest backstories and they always seem to involve drug dealers. And gosh, if all these stories were true then the guy would’ve had no time to paint!

CS: You mentioned Alice Cooper’s red Electric Chair that you dealt with before. What was the value of an Electric Chair back in the ‘70s?

RP: Cooper’s version was bought by his girlfriend Cindy Lang who was part of the Warhol scene. In ‘72 she bought it for $2500. Back then that was not a lot of money for a Warhol. People had no idea, including myself, that this art would become so valuable. Do you know how many valuable paintings I have let slip through my hands?

My wife gets very angry when I mention this. She’s like: ‘I don’t want to hear it - why didn’t you just keep one!’ But as a dealer I was in the moving business, not the storage business. You sold things. That’s how you made a living. But now it's a different world with dealers. You have to come from vast wealth and that's the biggest change I've seen since getting involved in this world.

CS: Great dealers are normally collectors first, in my experience. These people collect and collect, and they get to the stage where they want to keep that collection moving and rotating.

I think it’s fascinating that earlier you mentioned these turning points. In the early 2000s, contemporary art was in vogue, but the big money was still in the impressionist and modern market where the value had grown in the ‘70s & ‘80s, what was it like then?

RP: The market changed in the 70s. If you were an adventurous collector in the 70s, you bought modern art. Most people at the time bought impressionist works. Modern art was like Rothko, de Kooning and Pollock and that was considered adventurous. If you collected contemporary art, like Pop art? Boy, you were going out on a limb and you were crazy!

The biggest change I've seen since I got involved in this industry is how it's transitioned from the art world to the art market. When I started doing this, you sort of knew darn well, if you bought a good quality painting by a big name, that it would appreciate in value. But this wasn't the primary motivation. In the 70s, people actually cared about the art they were buying. Dealers would have conversations at artists studios about what they were doing and how they were painting for art history. But there has been an enormous shift. And that's OK. That's just life. Things evolve.

CS: Yes, and I think this is interesting in relation to the Warhol market in particular, because even now, when the market is such a huge focus, the tangibility of owning a print by Warhol means so much more than a piece of art. It’s owning a piece of the pop icon legacy, we think of the Factory and the parties, or you think about the record prices.

Incredibly high prices just capture people's interest, are you saying that this just wasn't the case back in the ‘70s?

RP: No, I can remember it. It was a lot more interesting. And I remember collecting art myself. I had a little Mao painting. (It’s gone now, alas!) I remember living with it and I got a thrill each time I walked by it. I didn't think, ‘Oh, this is worth twenty thousand dollars’, but ‘this is art history I'm living with!’ How cool is that? I bought it from the OK Harris Gallery, the one Ivan Karp ended up owning after he left Castelli. It was hanging in his office and he wanted $4,500 for it.

I remember when Warhol died, someone offered me twenty thousand dollars for the Mao painting. At this point, nobody had any idea what was going to happen investment wise. It could have gone either way, because there were a lot of rumours that he had produced so much work, because of the mechanical silkscreen process, that his studio was just stacked with these things. There was a risk that the market was going to get flooded and they would go down in value.

Anyway, $20,000 to me was a lot! So I took the money and I thought, ‘Man, am I a great business man or what?’ It's worth a million dollars now. But, the thing is, it wasn't the money. I actually missed the painting! It was very cool waking up to this thing, it was like a little icon in my house.

This is why people became art dealers - because it was interesting. You cared about art and liked art history. That’s the joy.

CS: As an authenticator of Warhol works, you must see a lot of fakes. What are the most faked Warhols?

RP: The most desirable prints on the market by far are the Marilyns, everybody wants a Marilyn! These are the most faked of all Warhol prints.

It’s so easy to copy a silkscreen that many fakes are actually quite good, but there’s always something that leads you to suspect something’s off. Have you ever heard of Sunday B. Morning? They came out in the ‘70s and made Marilyn prints - they were the same size, similar colour and similar silkscreen technique to Warhol. They even showed them to Andy, and he laughed, and signed the back of a few of them writing, ‘This is not by me - Andy Warhol’. They still make these prints! Sunday B. Morning prints passed off as real Marilyns at the time, but you can tell the difference if you know what to look at.

CS: I’ve loved the Marilyn series since I was a teenager, but I’m wondering, why do you think people love Marilyn so much?

RP: It’s associated with glamour and celebrity. The Americans have this funny fascination with celebrity, which Warhol tapped into. And it's especially true of celebrities that died young. Whether it was James Dean, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, all the usual suspects. Even Basquiat was part of that. Marilyn died relatively young. And as they say, when you die young, you leave a good looking corpse. There's still an aura of beauty and glamor to these people and the myth making starts to grow. She had that iconic look, that platinum blond hair and smile, and a curvy figure. It was just there.

CS: Nowadays these Warhol prints tap into something even more fundamental: untouchable celebrity. Celebrity doesn't exist in the same way anymore. I think it is that mystique that adds to the appeal of these works, the last of the untouchable celebrities, frozen in a time we don’t recognise anymore.

Equally, I wanted to ask you about Warhol’s interest in the celebrity macabre too - I think what Warhol does to these characters - as you say with James Dean’s car crash - he takes these terrible moments and gilds them, popularises them. Meaning even outside of his Death & Disaster series, his portraits take on some of that. For instance, Marilyn, to me, doesn't represent happiness and beauty. She represents a bird caged, do you agree?

RP: Yes, they represent tragedy. This is part of why certain things stand the test of time. When Warhol did this, it was after Marilyn died. Warhol's first New York show was at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, where he displayed the Marilyn paintings. The ultimate Marilyn painting was the Gold Marilyn, bought by the famous American architect Philip Johnson. He donated the work to the Museum of Modern Art. This gold Marilyn painting when you go to the Museum of Modern Art, it's one of the greatest paintings in art history. You can't explain it.

There are intangibles to everything, and that's what makes life interesting. It's what you can't explain all the time that is so valuable. You can't always articulate why, you just know it when you see it. It goes back to authenticity. I mean, the idea is we're all trying to lead authentic lives. You know, we're trying to be true to ourselves. Well, that's true with art. There are just certain pictures where you think, ‘it's a miracle, how did this thing happen?’ You can’t put your finger on why it's so great, but you just know it when you see it.

CS: On that note, what’s your favourite Warhol print of all time?

RP: I don't know if I have a favourite print, but I do tell collectors there may be some value in buying the Mick Jaggers. They're not cheap. A good Mick is probably £150,000 now, but I think they'll go up some more.

CS: Why do you think they’ll go up in value?

RP: Well, it was an interesting moment where, as you probably know, Mick Jagger signed them as well as Warhol. So they have an appeal to rock memorabilia collectors as well as art collectors. Mick Jagger is, again, one of those people where there’s just something about him, but you don’t know what it is. With the portfolio of ten, it's like the Marilyns, and I think they have a ways to go, even though they're not cheap.

CS: You must know Warhol’s Catalogue Raisonné inside out and back to front! Presumably you have people come to you often when something isn't in the Catalogue Raisonné?

RP: That's correct. See, that's a problem because there are things with every artist that fall between the cracks. Warhol in the 60s, with the Factory, it was sort of a free for all. There was no law and order there. Warhol wouldn't sign a painting until it was sold or was sent out for an exhibition because so many of his works were being stolen.

Warhol also did some strange trades. I did work for one of his attorneys from the ‘60s, who told a compelling story about doing some legal work and trading his services for Warhol paintings. It was very casual. Andy would say, “Oh, I owe you $2500. There's a stack of paintings unstretched in a pile over there. Just pick out what you want.”

So yes, I don't think a lot of his work was recorded. So when it came to creating a Catalogue Raisonné, there are things that just got lost in the fog. They talk about the fog of war. Well, the fog of the art world was the ‘60s. It was inconceivable that these works would be worth so much money now.

CS: Where do you predict the market will be in 10 or even 20 years time?

RP: Higher, eventually. But we can't predict any of this stuff. The art markets are a little bit different than the larger market for other investments because people do get emotionally involved with their pictures, whether they like it or not. When you hang a painting, you may look at it and become really proud of it. It becomes part of your own personal taste and your own personality. I love it when collectors pose with their paintings like they painted it. You know, you didn't paint that, you bought it! The artist painted it!

CS: What do you think Warhol would make of the market for his work today?

RP: Warhol cared more about the market than people know. There are a lot of stories where Andy was very aware of his paintings sold at Sothebys and Christie's, and it hurt him that Jasper Johns was getting higher prices than he was.

If someone asked Warhol about how much his market was worth and all the action nowadays, he'd say, ‘that's fabulous.’ He'd love it. He cared about money, but he did it in such a way that people went along with it and it worked.

Richard Polsky Art Authentication authenticates the work of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, and others — www.RichardPolskyart.com