Icons of Style, Screen and Silkscreen: Who Did Andy Warhol Paint?

Marilyn (F. & S. II.27) © Andy Warhol 1967

Marilyn (F. & S. II.27) © Andy Warhol 1967

Interested in buying or selling

Andy Warhol?

Andy Warhol

493 works

From Marilyn Monroe to Chairman Mao, Grace Kelly to Muhammad Ali, Andy Warhol painted some of the most famous faces of the 20th century. Fascinated by the spectacle of celebrity, Warhol appropriated publicity shots from the press and transformed them into high art, simultaneously elevating them to the status of religious icons and turning them into products to be reproduced as easily as a Campbell’s Soup can. Here we take a look at some of the figures that underwent the silkscreen treatment and their relationship to the great Pop artist.

Hollywood Stars

Marilyn Monroe

Warhol’s experimentation with the silkscreen reached new heights when, in 1962, following the tragic death of Marilyn Monroe, the artist took a still from the film Niagara and turned the actor into an icon. Warhol’s fascination with Monroe’s image and myth continued in the years following and in 1967 the artist created a portfolio of 10 screen prints based on the same photograph. This body of work would later become the largest screen print series of Warhol’s career, establishing him as an artist and garnering both critical and popular acclaim.

While Warhol never met Marilyn in person he was drawn to the status she held as sex symbol and starlet which led to her image selling millions of newspapers and magazines around the world. It is this idea of celebrity as commodity that perhaps first attracted him to repeat her recognisable features countless times in his Factory.

Elizabeth Taylor

Created in 1964, just a year after her iconic performance as Cleopatra, Warhol’s portrait of the actor, based on an MGM publicity still, has arguably become more famous than the actor herself, or, as critic Jerry Saltz put it, “Elizabeth Taylor is Andy Warhol’s painting of her.”

Funnily enough Taylor never owned a copy, something she told Warhol when they met on the set of her 1974 film The Driver’s Seat. According to Bob Colacello, author of the Warhol biography Holy Terror, Taylor had called the Factory to ask for a copy but had never received one or been called back. Naturally Warhol was horrified and offered to make a new version based on polaroids he could take then and there, but apparently the actor kept putting him off, telling him “I’m too puffy today”.

Grace Kelly

Andy Warhol’s portrait of Grace Kelly was commissioned and published in 1984 by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. As well as being a classic beauty of the golden age of Hollywood, Kelly may have appealed to Warhol as the subject for this series because of their shared roots in the state.

The portrait is based on a still from Kelly’s first film Fourteen Hours, from 1951, when the actor was on the cusp of becoming a superstar. In 1954 she would play James Stewart’s love interest in the Hitchcock classic Rear Window and two years later she would marry the Prince of Monaco in what seemed like a fairytale ending. But the story carried on and the event that may have had the most impact on Warhol, whose fascination with tragedy and celebrity was well known at this point, was her involvement in a fatal car accident which led to her face becoming front page news all over again.

Ingrid Bergman

In 1983 Warhol produced three screen print portraits of Ingrid Bergman, at the request of a Swedish gallery – Galerie Borjeson in Malmö – who later published the suite.

The series consists of two stills from Bergman’s films, The Bell of St. Mary’s and Casablanca, as well as a publicity portrait of the Academy Award winning actor in profile. These are titled The Nun, With Hat and Herself respectively. In each work Warhol highlights the iconic features of Bergman’s face that made her into the beloved star she is still known as today.

John Wayne

Symbolising the struggle for the West, the hardship of the pioneers, and man’s taming of the ‘wild’, the cowboy remains an enduring icon of American history and popular culture. As well as being the subject of numerous films, cowboys have been a consistent presence in postmodern art and Warhol, who made two Westerns himself, was not able to resist the urge to depict this symbol of romance and nostalgia, as best represented by one of the 20th century’s most famous actors, John Wayne.

Warhol depicts Wayne in true cowboy style, complete with Stetson, bandana and Smith and Wesson, his eyes narrowed in suspicion at an unseen adversary.

Growing up as an orthodox Catholic, Warhol would have been surrounded by saints and icons. Many critics think it is this devotion that he transposed into his portraits, seeing him elevate movie stars to the status of saints or even gods.

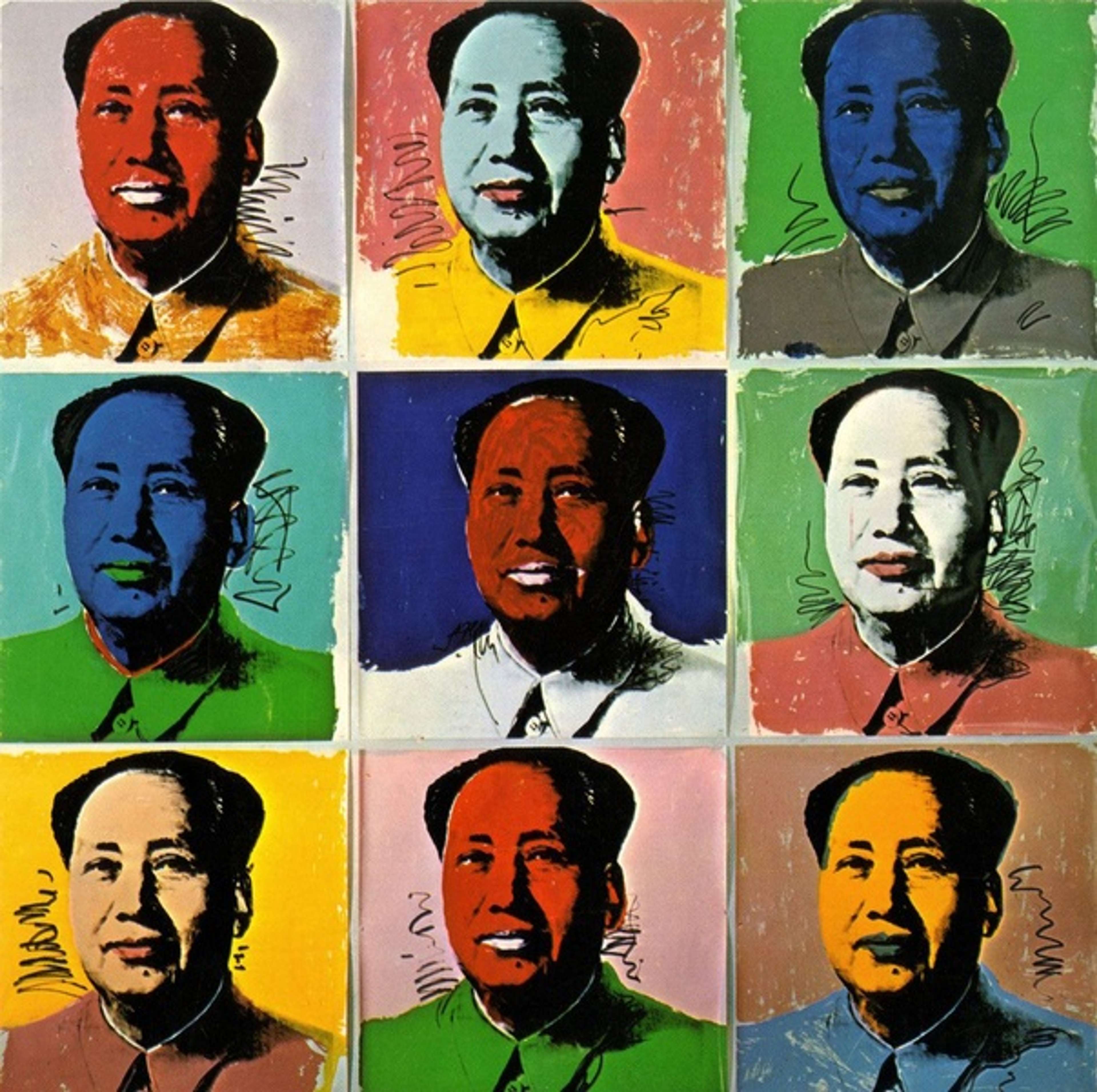

Mao Series @ Andy Warhol 1972-3

Mao Series @ Andy Warhol 1972-3Controversial Communists

Chairman Mao

One of Warhol’s most recognisable portraits is that of the Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976). His depiction of Chairman Mao was set in motion by President Richard Nixon’s visit to China, an event which was widely publicised on the world’s media stage as an attempt to end years of diplomatic isolation between the two nations. As a result Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol’s long-time dealer and supporter in Zurich, encouraged Warhol to return to painting by making a series of portraits of the man he saw to be the most important figure of the 20th century.

The cult of Mao led to the Chairman’s image becoming disseminated across China and it is perhaps the inescapable ubiquity – similar to that of a Hollywood star in the press – which led Warhol to be attracted to the idea. Commenting on the series he remarked, “I have been reading so much about China. They’re so nutty. They don’t believe in creativity. The only picture they ever have is of Mao Zedong. It’s great. It looks like a silk screen.”

Lenin

Portraying one of the most important political figures of the 20th century, Warhol’s Lenin series shows the father of the Russian Revolution drenched in red – the colour of the Communist party – and black in two different versions of the portrait.

Created in 1987, just months before Warhol’s untimely death from surgical complications, the series marks a maturity in the artist’s work and perhaps a revelation of the artist’s politics.

While Warhol openly declared himself to be a democrat he was not particularly involved in radical left wing politics, preferring instead to make occasional comments through his artworks that often portrayed protests, activists and political figures.

Sports Stars & Musical Maestros

Muhammad Ali

While Warhol’s first screen print of a film star was made in 1962 it would be another 15 years before he realised the appeal of depicting celebrities from the world of sport, stating “I really got to love the athletes because they are the really big stars.”

The artist’s Muhammad Ali portfolio was first commissioned by collector Richard Weisman as part of a series dedicated to sporting figures which included Chris Evert and Jack Niklaus alongside Ali. In 1978, when the series was first published, Ali was already regarded as a sporting superstar, having just become the World Boxing Association Heavyweight Champion for the third time. He was renowned for his agility and stunned both opponents and spectators with his consistency, winning fight after fight for more than a decade.

Unlike many of Warhol’s screen prints, in this instance Warhol himself shot the original photographs of the sitter, travelling to Ali’s training camp in Pennsylvania to photograph and interview the boxer.

Beethoven

Warhol might be better known for his portrayals of Studio 54 icons such as Mick Jagger and Grace Jones, but before his death he also produced a series of portraits of one of the most celebrated composers of all time, Ludwig van Beethoven.

Based on an 1820 portrait by Joseph Karl Stieler, Warhol’s version overlays the composer’s likeness with a sheet of music for the Moonlight Sonata, Beethoven’s most famous work, effectively replacing the man with his most well known product.

Mick Jagger

One of Warhol’s most recognisable series of prints is that of the British rock star and lead singer of the Rolling Stones, Mick Jagger. This portfolio of 10 screen prints produced in 1975 is evocative of the celebrity status of both the subject and artist, who were at the height of their fame at this time.

Warhol met Jagger in 1963 during the Rolling Stones’ first tour to the United States, just before the band reached international popularity. The pair formed a friendship and professional relationship that became the foundation for several years of artistic collaboration. Most famously, Warhol was commissioned to design the iconic cover for the Rolling Stones 1971 album Sticky Fingers, which became an instant classic with its risqué imagery that seemed to encapsulate the attitude of rock and roll. In the summer of 1975, while Jagger and his wife were renting Warhol’s home in Long Island, the artist took the opportunity to photograph Jagger, capturing a variety of expressive images that would form the basis of his next portfolio of prints.

Avant-Garde Artists

Martha Graham

As well as film and politics, Warhol looked to the worlds of art and dance for his muses. It is no surprise, therefore, that Warhol chose to depict Martha Graham, known as the ‘Picasso of Dance’, in a series of prints that encapsulated her unique talent and style. Credited with revolutionising dance in the 20th century, the performer and choreographer was renowned for creating a language in movement based upon the expressive capacity of the human body, and her technique is still practised by dancers today.

Graham founded New York’s Martha Graham Dance Company in 1926 and Warhol’s screen prints were produced to mark its 60th anniversary, in celebration of her contribution to the discipline. The Martha Graham Series comprises: Letter to the World (The Kick), Lamentation and Satyric Festival Song, all of which showcase the physical and emotional depth of Graham’s unique movements.

Joseph Beuys © Andy Warhol 1980

Joseph Beuys © Andy Warhol 1980Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys is widely considered to be one of the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century and his impact on Warhol’s practice is evident in the latter’s more experimental work.

In 1985 the two artists collaborated, together with Japanese artist Kaii Higashiyama, on the ‘Global-Art-Fusion’ project which involved sending a fax of three drawings by the artists around the world in a message of peace during the Cold War. They only met for the first time, however, in 1979 when Warhol took a polaroid of Beuys from which the series of portraits is painted and, later, became print. Warhol was immediately a big fan of Beuys stating, “I like the politics of Beuys. He should come to the US and be politically active there. That would be great… He should be President.” They only met a handful of times after that but maintained a mutually respectful relationship, while continuing with their vastly different practices.

Royals & Patrons

Queen Elizabeth II

Warhol famously once claimed that he wanted to be “as famous as the Queen of England” and with the Reigning Queens series it is easy to see how he might have achieved that ambition.

By combining bright commercial colours with royal icons the works seem to be both an homage and a satire of kitsch aesthetics. The monarchs, frozen in time and colour, are now on equal footing with the models, actors and musicians that form Warhol’s oeuvre. Showing his mastery of screen printing as a medium, Warhol multiplies and transforms Queen Elizabeth – whose face was already renowned the world over thanks to the currency and stamps that bore her profile – into a Pop Art icon through his daring use of colour blocking and the addition of hand drawn lines for emphasis.

Jackie Kennedy

Warhol’s fascination with beauty and tragedy is exemplified in his series of portraits of Jackie Kennedy – America’s version of royalty – which depict her both before and after her husband’s assassination.

The first work from the Jackie Kennedy series shows a glamorous woman smiling into the camera in the style of the Marilyn and Liz portraits, her white face glowing against a red background. This is followed by a version which appropriates newsreel footage of JFK’s funeral, showing an almost unrecognisable Jackie in a flat monochrome.

Finally one of the most famous works from the series shows the before and after together in a haunting combination that acts as a kind of mixed up storyboard for a film, where Jackie can be seen simultaneously in her pink Chanel suit moments before the assassination, attending the swearing in of Lyndon B Johnson, and finally looking grief-stricken at her husband’s funeral. Though she wasn’t a film star, an athlete or a musician, Jackie had captured the hearts of women all over America and by choosing to focus on her rather than her husband, Warhol’s portfolio presents a portrait of grief haunted by the spectre of past happiness, all soaked in the glamour of 1960s America.

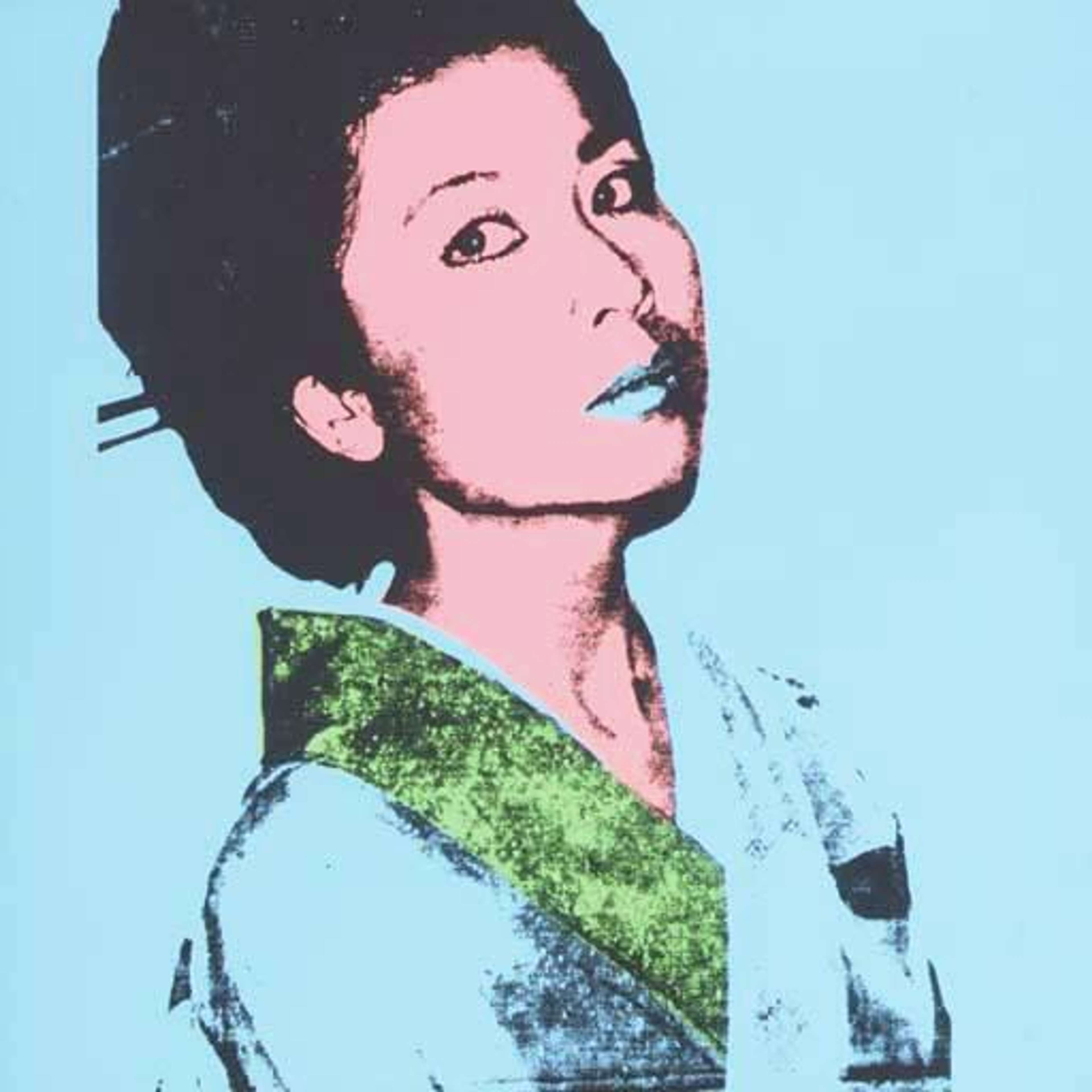

Kimiko Powers

After he became known for making Pop Art portraits of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor and Mick Jagger, Warhol was soon in demand for commissions from wealthy patrons who also wanted to be immortalised in print.

John and Kimiko Powers had a large collection of Pop Art and in 1972 John commissioned the artist to make a portrait of his wife. Warhol visited their apartment to take some Polaroids of Kimiko from which to work, an episode she recalled in a 2001 interview: “And he said to me, ‘Turn your face up. Turn your face to the side. Oh, it’s beautiful… oh gee that’s great.’ He took Polaroids, one after another. Afterwards, when we were finished, he put them all over the floor and asked, ‘Which one do you like?’ I said, ‘You’re an artist, you decide.’” This marked the beginning of a long friendship between the artist and the model, whom he would paint again.