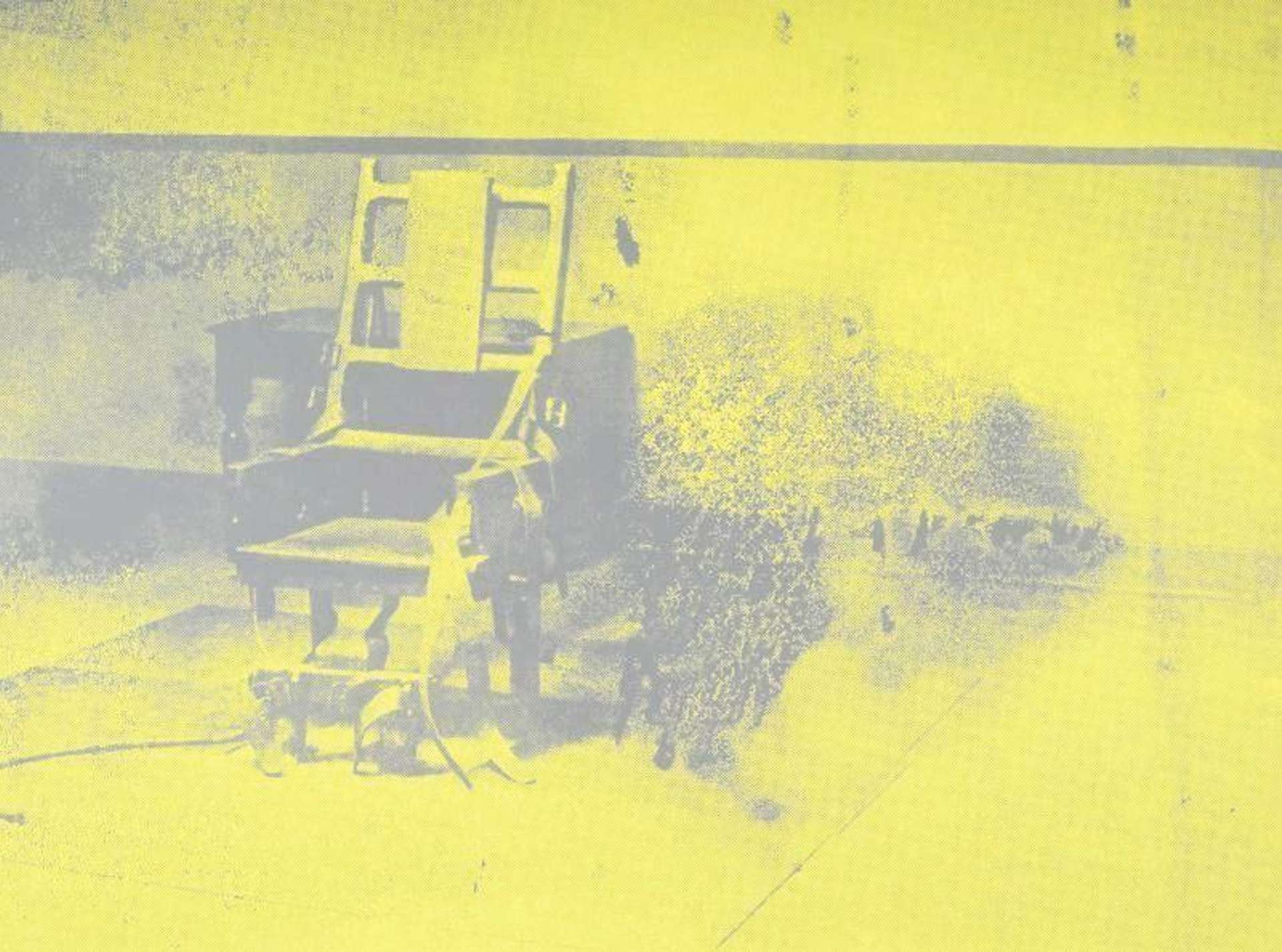

Electric Chair (F & S 11. 81) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F & S 11. 81) © Andy Warhol 1971

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

Read Chapter Three of Richard Polsky’s exclusive mini series on the world of Andy Warhol authentication.

Chapter 3

When you’re buying a work of art, one of the most important things is determining authenticity. The stakes can be high. The recent documentary, The Lost Leonardo, tells the story of the da Vinci painting Salvator Mundi — which sold for a record US$450 million at Christie’s (2017). Its purchaser was Mohammed bin Salman, the notorious ruler of Saudi Arabia, often referred to as MSB. The kicker is that the vast majority of the art world (myself included) believed the painting was a forgery.

At times, the scams that dog the art world appear endless. Prior to the Salvator Mundi controversy, the venerable Knoedler Gallery (they had been in business for 165 years) was forced to close after getting caught selling fake Jackson Pollocks, Mark Rothkos, and Robert Motherwells. A documentary, called Made You Look, recounts how the gallery’s director, Ann Freedman claimed she was duped by an obscure private dealer named Glafira Rosales. Ms. Rosales offered her access to a trove of “previously unknown” Abstract Expressionist canvases which belonged to a long-deceased collector from Mexico City. Adding a further touch of the absurd, Rosales refused to divulge his identity, referring to him only as “Mr. X.” What was so remarkable was that Freedman went along with it. Then again, given the substantial commissions she received, maybe it wasn’t. There was also one other small detail — the name Jackson Pollock was misspelled on one of the paintings.

While most cases aren’t this high-profile, there’s a steady flow of collectors, dealers, and auction houses seeking guidance on whether their paintings are genuine. Prior to 2012, all they had to do was contact the art authentication board of an artist’s respective estate. These committees offered authentication services designed to keep the market free of counterfeits and maintain each painter’s legacy. But in 2010, a lawsuit was brought against the Andy Warhol estate, by a British collector named Joe Simon. In 2011, after the Warhol estate spent US$7 million on a top-flight legal team to successfully defend it, by wearing down Simon’s lone attorney, they decided to get out of the art authentication business. This triggered a classic domino effect. One by one, the authentication boards for a number of artists’ estates followed suit: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, and Isamu Noguchi. The Jackson Pollock estate had already closed up shop in 1996. Currently, the Alexander Calder estate — an artist whose market is inundated with questionable hanging mobiles — refuses to validate work.

Changing Course: Adapting to a Commercialised Artworld

This was the shaky state of affairs that the art world found itself in when I started Richard Polsky Art Authentication in 2015. In retrospect, my decision to get into the art authentication business had been simmering for a while — I just didn’t know it. As a result of having written two books about Andy Warhol, I would receive an occasional phone call or email from a collector who believed he owned a Warhol, but needed confirmation. Each of them expressed their dismay that the Warhol Art Authentication Board was no longer in existence and wanted to know whether there was an alternative. Alas, there was none.

These inquiries eventually had a cumulative effect on my psyche. They came to a head one afternoon when I was sitting in Rancho Nicasio, a rustic cowboy bar covered in hunting trophies, in West Marin County (California). The restaurant’s spacious bar was popular with locals, as well as bikers passing through on their way to Pt. Reyes Seashore. Sipping a cold beer, in a funky bar, created just the right vibe to contemplate my future.

I was newly married, at the age of 60, and was seriously concerned with making a living. The art business was rapidly changing. I had been an art dealer since 1978 and suddenly woke up to the fact that the art market had gotten away from me. As a dealer in the secondary (resale) market, I discovered that I could no longer afford to buy inventory. Sotheby’s and Christie’s were vacuuming up everything in sight. In short, the scene had transitioned from the art world to the art market. It was now all about investment.

If you couldn’t afford to buy inventory, you couldn’t control your destiny. A typical example was the market for Ed Ruscha’s “Ribbon Letter” drawings. These magical works illustrate a single word or phrase with letters shaped like three-dimensional pieces of ribbon. I once mounted a show of Ribbon Letter drawings at my San Francisco gallery, Acme Art (in 1986). At the time, you could buy a nice one for US$3,500. By 2015, the same drawing, which typically depicted a word like “Cherry,” would retail for approximately US$450,000. Unless you were extremely wealthy, you could no longer afford to stock very many of them. This pattern was repeating itself with all of the other artists whose works I regularly bought and sold: John Chamberlain, Joseph Cornell, Andy Warhol, and even the Outsider artist Bill Traylor.

Something had to change in my life. Even though my new wife Kimberly was employed, life in Marin County was expensive, and generally required two incomes — unless you worked in tech. After a few sips of my Lagunitas IPA, I challenged myself with the question, What’s the biggest problem in the art market? The answer came quickly; all of the fakes and forgeries which had inundated the field — with nowhere to verify them. It was at that very moment that I decided to start an art authentication service which specialized in Andy Warhol — one of the most faked artists around.

What Makes a Legitimate Art Authenticator?

Technically, anyone can become an art authenticator. There is no regulatory body in the art world that’s the equivalent of the SEC in the stock market or the FDA for the health field. For that matter, the entire art market is unregulated. While a lawyer has to pass the difficult Bar exam, and a physician has to pass a tough series of Medical Boards, an art dealer, museum curator, art advisor, or auction house specialist doesn’t have to qualify for his position.

In order to successfully operate an art authentication service, you have to be good at three things. For openers, you must possess a comprehensive knowledge of an artist’s entire oeuvre. If you take an artist like Andy Warhol, not only do you need to know about the history of each body of work, but you need to understand the context it was created in. You also have to understand Andy’s working methods, his tendencies, and his idiosyncrasies. Second, it behooves you to know how to analyze a painting and translate the results into a coherent written report. Finally, you have to be able to monetize the business so you can make a living.

The First Steps Towards Opening An Art Authentication Business

When I took stock of my qualifications, I realized there were a few art world professionals who knew more than I did about Andy Warhol. There were also a small number of scholars who were better writers than me. And I assumed there were several dealers who were superior businessmen and businesswomen. However, I felt confident in my overall ability to navigate all three categories at a high level. I looked back on the exhibitions my gallery held, the books I had written, the innumerable articles I had authored, and the connections I had established — and felt good about my prospects.

Starting a new online enterprise from scratch is complicated. Even devising a name for my service had to be pitch perfect. The first order of business was to design a website that was attractive, functional, and easy to navigate. This was quickly followed by hiring a lawyer for general legal advice and formulating a disclaimer. A lot of thought was given to what to charge for my services. I also had to open a Paypal account to collect payments. Then there was the task of building a comprehensive reference library. Once I felt everything was organized, and the website was stress tested, the final step was creating a publicity campaign.

As a writer, I had always maintained good relations with the press, which came in handy. Not surprisingly, all of the journalists I contacted asked the same question: “Aren’t you afraid of getting sued?” I explained that I planned to protect myself by having clients sign a one-page disclaimer agreeing not to sue me if for any reason they were unhappy with my opinion. However, the best defense was transparency. Whether I verified a client’s painting or rejected it, he received a clear concise report, which explained step by step how I came to my conclusion. The Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board was often sued by disgruntled collectors who felt stonewalled when they asked why their painting was stamped “DENIED” on the back (in red indelible ink) — and weren’t given an explanation. The Board’s policy was never to explain anything because they claim they didn’t want to aid counterfeiters.

Warhol's Catalogue Raisonné: Source of Verification or Mystification?

Then there was the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, which provided another level of frustration. A catalogue raisonné is an illustrated compendium of (almost) every painting by an artist. Producing a catalogue raisonné is a herculean task and can involve decades of research. The Picasso catalogue, known as the “Zervos” after its author, has an incredible thirty-three volumes. So far, the Warhol catalogue has seven volumes — and counting. It opens in 1961 and eventually will run through 1987.

Despite the fact that the Warhol catalogue itself is outstanding, some of the policies of its editors are questionable. I was exposed to their bewildering approach, to working with potential owners of Warhol paintings, when I received a phone call from the wife of hockey great Rod Gilbert:

“Mr. Polsky? This is Mrs. Gilbert (using the French pronunciation Jill-bare) — Rod Gilbert’s widow.”

Even though I didn’t follow hockey, I certainly knew who Rod Gilbert was. I even knew he once played for the New York Rangers.

“I’m calling you because my late husband received a 40” x 40” portrait of himself from Andy as part of his compensation for participating in the ‘Famous Athletes’ series.”

I was already familiar with Warhol’s Famous Athletes series. In 1977, the collector Richard Weisman, son of the famous Los Angeles collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman, commissioned a group of ten portraits (with multiple images of each subject) depicting some of the most well-known athletes of their times. The most valuable paintings — by far — turned out to be the portraits of Muhammed Ali. The least valuable — not surprisingly — were of O.J Simpson. Among the group were paintings of Rod Gilbert.

Mrs. Gilbert continued, “I recently had two of the editors from the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné come to my New York apartment to view the painting. They spent about an hour here, took some photographs, and made all sorts of notes. When the Warhol people were getting ready to leave, I asked them to assure me that the painting would be included in the catalogue. I wanted to sell it and was told that its inclusion was the difference between being able to get a lot of money for it — and not. But when I asked the editors, all they said was, ‘You’ll find out when the appropriate volume is published.”

She paused, “Why couldn’t they just have said, ‘You’re Rod’s wife — we know Andy gave Rod this canvas for posing for him. Of course the painting is real and will be included!”

When I offered to authenticate the painting for Mrs. Gilbert, she didn’t want to pay for my research, because she claimed she knew it was genuine. The only way she would have been willing to hire me was if I guaranteed that Sotheby’s or Christie’s would take it. But that’s getting ahead of our story.

As the word got out that someone was “brave enough” to authenticate Andy Warhol, there was a steady flow of business. I was surprised by the pent-up demand from potential Warhol owners desperate to have their treasures validated. Soon, I decided to add several additional artists to the mix. Within a year, I began authenticating Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. While I was knowledgeable about each of their respective bodies of work and careers, I also knew a few former members of their art authentication boards, who I could consult with if I needed a second opinion.

Working with this triumvirate of artists — Warhol, Basquiat, and Haring — created a neat package because the three of them were friends during the 1980s. They fed off of each other’s creative energy and ideas. Warhol and Basquiat even collaborated on a group of large-scale paintings. Over time, I added a few more painters whose markets were riddled with forgeries: Jackson Pollock, Roy Lichtenstein, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Bill Traylor. With a group of seven artists now in my “stable,” I realized I had reached my capacity of what I could successfully handle.

As I was about to find out, much of my business would come from validating Andy Warhol’s paintings, sculpture, drawings, and prints. While there were plenty of clear-cut forgeries, there were also a surprising number of genuine paintings which flew below the radar. For openers, there were seven red 1964 “Self-Portraits,” that were part of the same group as the one Joe Simon owned. There was an amazing silver “Marlon” (Brando) that Warhol traded to his attorney for professional services. There were even a pair of colored “Campbell’s Soup Can” paintings, that may have been experimental, but looked right as rain when I examined them.

And then there was Alice Cooper’s “Little Electric Chair.”

Image © Christies / Marlon © Andy Warhol 1966

Image © Christies / Marlon © Andy Warhol 1966Keep reading: 'I Authenticated Andy Warhol'.

Read the previous installement of the I Authenticated Andy Warhol series here.

Richard Polsky is the author of I Bought Andy Warhol and I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon). He currently runs Richard Polsky Art Authentication: www.RichardPolskyart.com