Live TradingFloor

Henrik Riis is the CEO of Eyestorm and a leading specialist in the field of Damien Hirst’s Spot prints. Breaking into the artworld in 2011 by heading up one of the pioneering online galleries and publishers of limited edition contemporary art, Henrik Riis has a refreshing take on the artworld today and how it is fast changing.

Here Henrik talks to Charlotte Stewart about establishing Eyestorm, the changing landscape of art business off and online, the NFT boom and Hirst’s market today.

Charlotte Stewart: Henrik, it’s a pleasure to speak to someone with over 20 years in this industry, with a 360 world view of art in e-commerce, customer service and creative art management. Where did your career in the art world begin and how did you end up at Eyestorm?

Henrik Riis: My venture into the artworld was not planned. I have a background in technology, moving into advertising and this is how I later found myself in the creative industry. In 2008 I broke into the artworld, founding a gallery with an online presence - it was incredibly unsuccessful! This was ten years down the road in terms of online publishing and we still had many sticking points in the online world to work through.

It was through this early gallery venture, a side business of sorts, that I was introduced to Eyestorm. I was familiar with many of the artists Eyestorm were representing at the time, but that was not really the point of my intrigue, it was more to do with the business side of things. What’s important is that I was primarily drawn to selling art online.

There was a restructure of Eyestorm in the early 2000s where the company was asking themselves, “do we follow the route of publishing limited edition prints with fantastic artists or do we move towards a traditional gallery model?” By 2011 it was moving into the traditional gallery model.

The gallery model was not my intention with Eyestorm. I had no experience in the artworld and came into it very naive. I believe this naivety was more of an advantage than anything else. I wasn’t restricted by preconceived notions of things you could and couldn’t do in the art world. As a result we tried to work with both the traditional gallery model and were innovative in how to build a truly interesting and unique business.

CS: Back in 1999, it was founded to offer pieces by some of the world’s most celebrated artists - not just Hirst, but Jeff Koons, Ed Ruscha and Helmut Newton to name a few. Now it focuses on both established and emerging artists - what were the defining moments in getting Eyestorm to where it is today?

HR: There have been many defining moments during my time with Eyestorm. From 2011 I knew that I needed to work with clients on a one-to-one basis to understand how the artworld operates. I started out by attending art fairs with Eyestorm. I thought, ‘I’m a smart guy, I’ve done this before. Surely I can corner the art world?.’ I quickly realised that the artworld operated somewhat differently to other business ventures…

One of the harder moments during this time was learning that art fairs were not a sustainable business. You have to spend a lot of time and manpower as a business, across 3 or 4 days, and the probability of getting it right at an art fair, in gallery business terms, is not good. Art fairs are a bad bet. They were a great way to meet people at the time, but predicting their commercial outcome was impossible.

There are very few galleries in the world where art fairs actually work. There is a top end of the artworld where they make a lot of money, but there is a long tail of galleries where a majority of them don’t make even a decent income. Those who run galleries and attend art fairs do this largely because it’s something they’re really passionate about.

We did a lot of the Affordable Art Fairs, it’s a well functioning art fair. We then tried Christie’s Multiplied Art Fair - the only fair in the UK dedicated to contemporary art in editions.

CS: I couldn’t agree more, the Christie’s Multiplied Fair was a great PR exercise whether it was a commercial enterprise for either the auction house or the galleries is debatable. It’s interesting that you mention the Affordable Art Fair from back in 2016, when it was a relatively new concept, right? These days I believe whilst ‘affordable’ is relative, we’re still talking £4,999 at the ceiling for artworks. They’ve reported astonishing sales off the back of it in recent years, pre-pandemic, but my experience is that most people who attend are buying lower than this £4-5k bracket. Both Multiplied and The AAF’s footfall is there to buy one key piece, they’re not collectors - yet! It’s such a different beast to some of the larger, mega touring fairs like Frieze, which are essentially fantastic networking opportunities.

HR: Yes. I totally agree - The Affordable Art Fair is like a sales fair, whereas some of the others are marketing fairs. But if you are a gallery and you have a budget of £250,000 for Frieze or Art Basel, you need to be sure you can use it as a marketing tool afterwards. And very few galleries can do that.

So by 2018, Eyestorm abandoned the art fair model. At this time we were doing a lot of publications and limited editions. So what was the next stage? This was when I established that one of the things I enjoyed the most was dealing.

There’s that old saying that the worst thing for entrepreneurs is that they have to deal with customers. I completely disagree. Ultimately, what I actually found was that it was the dealing aspect of the artworld that I enjoyed the most, and I attribute this to the fact that I had been a collector for 20 years before this. Rudolf Zwirner’s autobiography notes that: ‘all serious collectors at some point become dealers’. I think this is so true!

CS: I agree and see it so often. You see it deeply in the Prints & Editions market - it’s the same story for our founders Ian & Joe - who founded MAB from the need they saw to provide better solutions to collectors just like them. Any collector who commits to a particular category, at some point, will want to be part of that ‘collecting carousel’. Working with collectors over the years - whatever their niche - what connects them is the idea that a collection is never finished, and is always evolving. How did you start collecting?

HR: I started in the deep end. In the early 1990s I stumbled across a few fantastic pieces and within a year I started to buy artists like Karel Appel from the CoBrA group and so on. It was this particular group of artists that fascinated me the most - so you could say that this was how I started and it was this passion for a particular artist group that sparked my interest in collecting.

It’s interesting because now there are many different reasons for why people decide to collect. For some it’s an investment opportunity, that you can make money on a print or an artwork. For others, it’s a passion thing and you are buying something that you love.

What most gallerists get wrong, in my opinion, is that the people involved with the galleries are primarily not collectors. I would say it is almost impossible to make money from a gallery in general. You can make a living, but you cannot make a very good business out of it. What you can do however, as a collector, is use the gallery as a great marketing tool. Just like how an art fair can be a marketing tool for a gallery. The secret to success in my opinion? Combine your passion for collecting with your gallery business.

It’s easy for me to say this from my background in technology. I started with zero but started in a completely different industry. It’s difficult to start from nothing in the artworld and work your way up. It takes a very long time. But all good things take a long time.

CS: When did Eyestorm first begin working with Hirst, and how did this correlate with selling the works online?

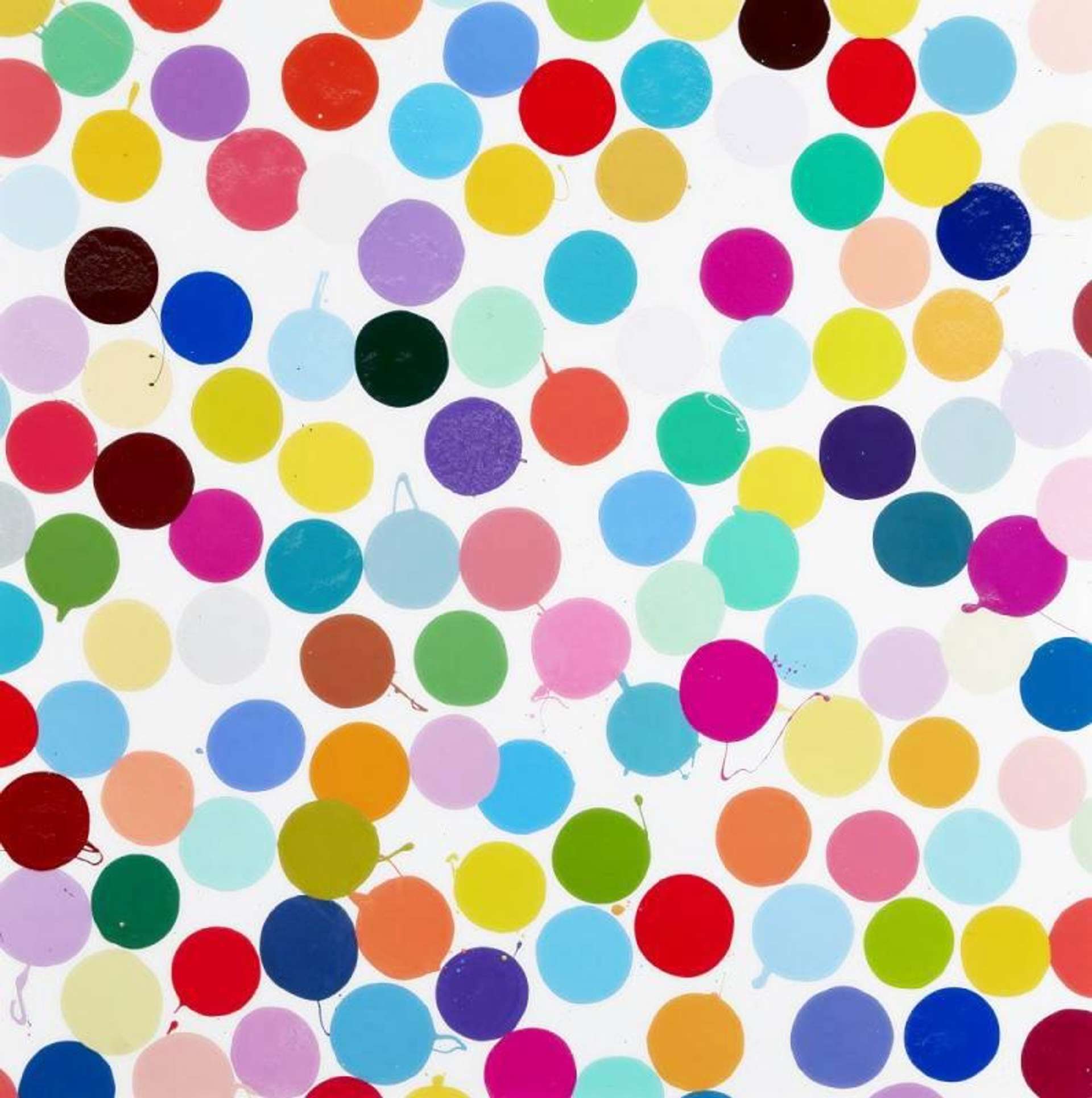

HR: In 2000, Eyestorm collaborated with Damien Hirst on three limited edition Pharmaceutical Spot prints, Valium, Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) and Opium. This was at a time when Eyestorm came up with the - then novel - idea to sell art online. They approached emerging – now globally successful – artists like Hirst and Jeff Koons and were, to my knowledge, the first company to sign artists with a fee to entice them.

CS: Of all the Hirst works we help change hands, Spots seem to be eternally popular, but why? Is it that they are just universally recognisable, synonymous with the artist? What do you think makes them so special?

HR: The Spot prints appeal to people because they are so visibly easy to understand. There’s not one reason because there’s not one kind of collector, but there are a few things that seem to appeal.

First of all, they are instantly recognisable as Hirst’s work and this is what gives them the ‘wow’ factor and is the reason why people want to hang them in their homes. Related to this, Hirst signs his Spot prints on the front of the work, when he should really sign them on the back. This is a deliberate move, heightening their appeal to those who want a distinctly recognisable Hirst print. Personally I’ve always been annoyed by this signature, aside from its value, the signature gets in the way of the overall aesthetic of the Spots. But it is the Hirst name where the value of the prints primarily lies - and the Spots represent the unique Hirst brand.

CS: Have you noticed any changes in the Hirst market over the last few years - and how do you think new releases affect older works?

HR: I think it all comes down to disposable income. If we think back to 2016, people forget Hirst prints were selling below £10,000. This is a middle ground. Most people don’t have £10,000 to spend - but at the same time, those who have £100,000 will not be buying works at £10,000. For the very serious collectors this kind of Hirst print is not interesting and for the emerging collectors it’s not affordable.

CS: So it fell between two camps…

HR: Exactly, but I think with these editions, what changed was the shift in the economy - this started to move before Covid, but it’s the pandemic that has put more power onto it. There is a group of people who have made a lot of money over the last two years, but people are worried about the financial market and if it’s overheated - so where do you put your income? You put it in art.

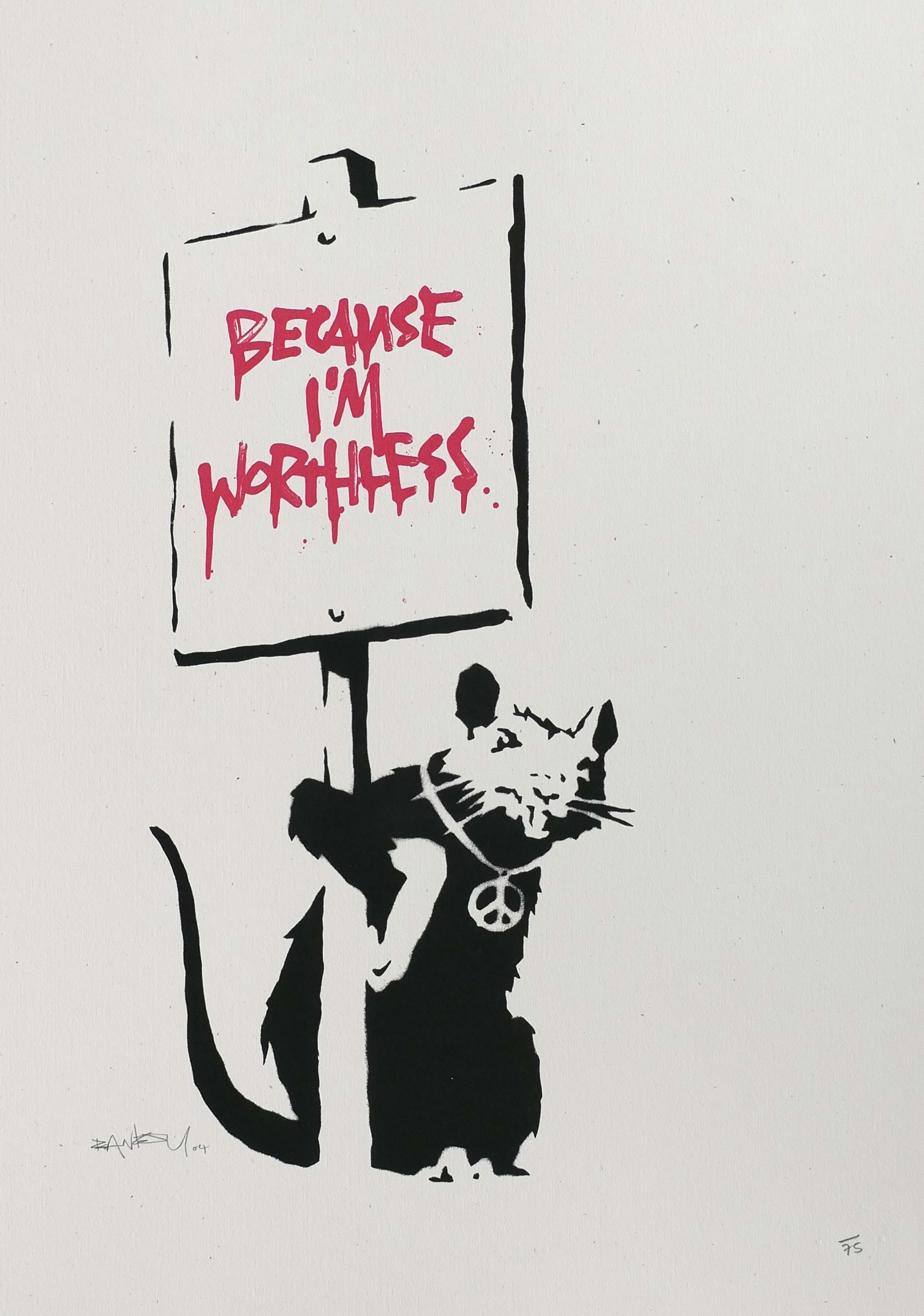

CS: We see a lot of narrative around diversifying your portfolio and investing in the art market at the moment, but I’ve heard stockbrokers argue that you can’t compare the speculative nature of the art market to equity. As you say, the market for Damien Hirst prints and editions occupies a middle ground in the art world between long established markets like Andy Warhol and booming fast reward markets like Banksy.

HR: Yes, and in terms of portfolio diversification, we have to keep in mind how the art market works. Most of what we do in the art world, if translated into the banking sector, we would be in trouble. For instance, the transactional costs of buying and selling art are significant and in fact they are so big that other industries would not accept it.

CS: Agreed, there are a lot of hidden fees in trading artworks, particularly at auction and in highstreet galleries where they have to make a huge margin to support the model. Back to diversification - would you suggest people collect Hirst to diversify?

HR: I understand diversification, and it can work well in the Warhol market, but I don’t think you should use Hirst as a way to diversify your asset portfolio. Too much can go wrong. So yes, up to the £25,000 mark is still an early collectors market, but it is certainly a market where you don’t want to put money in and see it fall the following year.

CS: What’s your opinion on purchasing HENI editions' latest releases?

HR: It’s interesting how they have twisted things to suit them. Rather than creating huge interest around an edition and attracting buyers with the idea that the edition is limited, HENI instead keep their editions open ended for a certain period of time and define the edition size thereafter. It’s quite opportunistic. But in a really interesting way.

CS: Are you interested in NFTs?

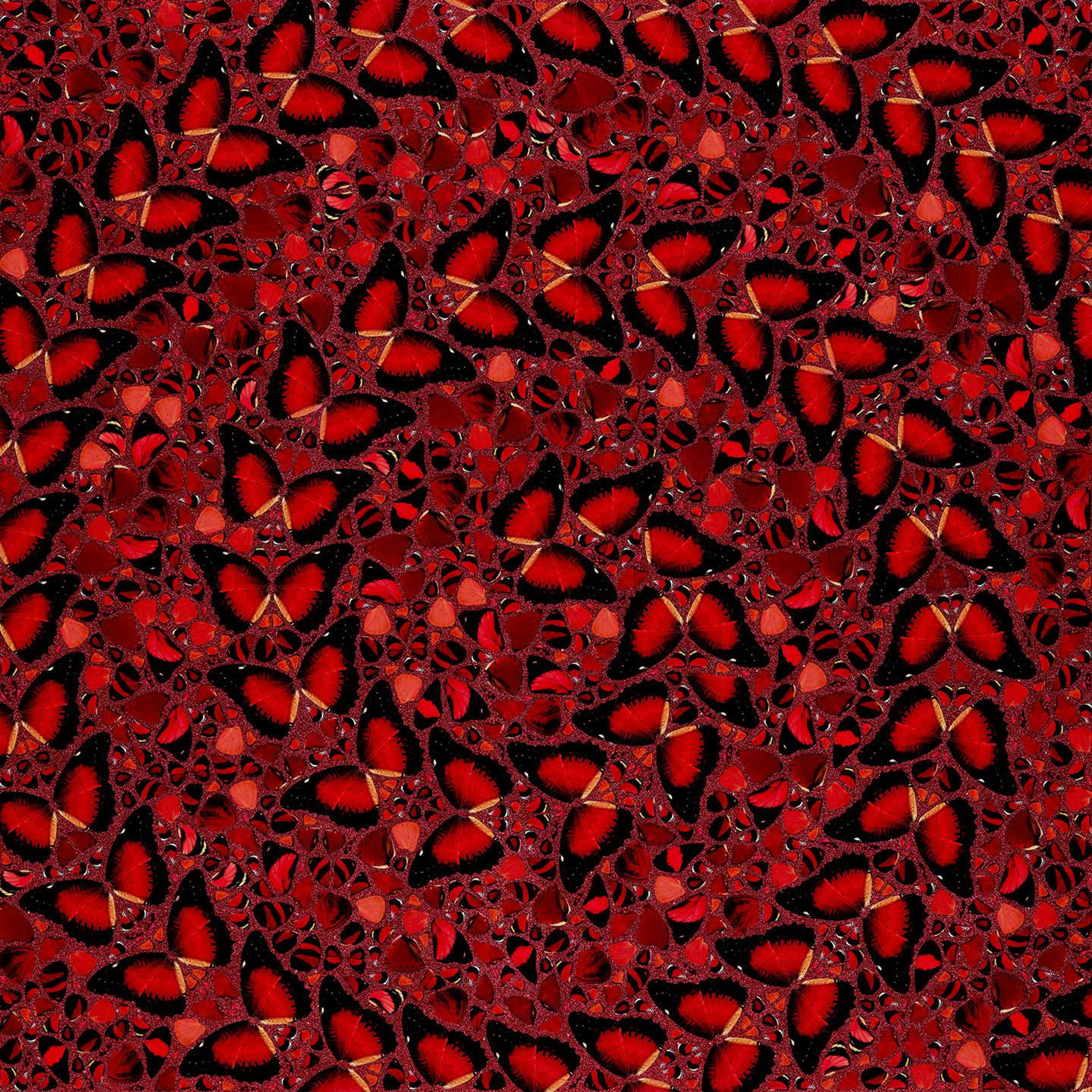

HR: I don’t think we can talk about trends in the Hirst market without mentioning NFTs. I never bought The Currency series, Hirst’s NFT collection, but I think it was a brilliant way of creating an edition that would be successful in the long run. Conceptually, each digital NFT that makes up this series is unique as they correspond to a physical artwork. The fact that the buyer can choose between the physical work and the NFT is pretty smart in marketing terms, as it appeals to a whole range of collectors.

The Currency is also Hirst’s first NFT series and so this gives it great weight in terms of value and demand. I’m less convinced by The Empresses, but this is largely because it is the follow up to The Currency. I don’t think The Empresses is as well thought through. I still think a lot of people are buying it because they felt they lost out on The Currency – but I think they will be disappointed.

CS: So you aren't interested in buying NFTs?

HR: No. I’m being asked this all the time, and seriously? I don’t know. I don’t own any NFTs myself. I wish I could say that the NFT boom is a generational thing, but then I think, maybe I’m just old fashioned. The truth is I don’t know whether NFTs are here for the long run or not, I don’t think anyone knows yet. I do think select NFTs will be successful, just like select cryptocurrency will be. In saying that I would invest in crypto over NFTs any day.

CS: I think what is interesting is the way that NFTs are beginning to attract a new generation of buyers who previously might not have been attracted in the traditional market. NFTs have almost become an entry point into the market and this can only be a positive thing for everyone - do you agree?

HR: Cryptocurrency and the traditional art market seem miles apart from one another but NFTs are beginning to bridge this gap. The turn towards the online market that Eyestorm and MyArtBroker are part of is a natural progression within the art market today, as well as what is happening elsewhere in the world right now. The Covid-19 pandemic has speeded up this process and the fact that the NFT boom has coincided with the pandemic is like throwing gasoline on a fire!

This conversation has been brought to you by MyArtBroker, you can contact Henrik Riis via Eyestorm at eyestorm.com.