Triptych

Inspired By The Oresteia Of Aeschylus

These prints after Francis Bacon’s 1981 painting Triptych Inspired By The Oresteia Of Aeschylus, merge Bacon’s fascination with Greek tragedy with the tragedy of George Dyer’s suicide. The Oresteia is a trilogy by Greek tragedian Aeschylus, exploring parental violence, trauma and death— all themes that haunt Bacon’s art.

Francis Bacon Triptych Inspired By The Oresteia Of Aeschylus For sale

Triptych Inspired By The Oresteia Of Aeschylus Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oresteia Of Aeschylus (centre panel) Francis Bacon Unsigned Print | 14 Nov 2013 | Swann Galleries | £1,403 | £1,650 | £2,200 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

This collection of prints by Irish-born artist Francis Bacon takes its name from a 1981 painting entitled Triptych Inspired By The Oresteia Of Aeschylus. This stand-out example of Bacon’s unique visual style was produced after artist’s so-called ‘Black Triptychs’ – paintings created following the suicide of Bacon’s muse and onetime lover, George Dyer, in 1971. Drawing from both 5th century BC ancient Greek tragedy and Bacon’s own tumultuous past, the three-part work is situated at the intersection of painting, literary intertextuality, and personal testimony. It can be read as both a visual transcription of The Oresteia – a trilogy of plays by the so-called ‘father of tragedy’, Aeschylus – and an exploration of the artist’s consciousness, particularly the traumatic after-effects of his violent childhood.

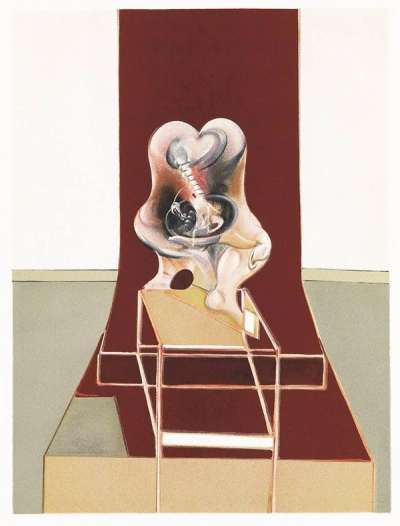

The second example of a major Bacon work to draw from Greek antiquity, the painting joins Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion in making pointed visual reference to The Oresteia: three tragedies that recount particularly violent tales of revenge and death. In the print Oresteia Of Aeschylus (centre panel), we are party to a particularly ‘Bacon-esque’ rendering of the body; varyingly human and inhuman, a crouched, mutilated figure stands in front of one of the artist’s signature framing devices – a geometric plinth – exposing its spine to the viewer. In the print Oresteia Of Aeschylus (right panel), the right panel of the triptych is exposed in all its detail; a fantom-like figure is held in suspension in a three-dimensional ‘cage’, traced with a series of economical lines of black paint. Recalling the fluid, seeping substance of the human body in earlier Bacon paintings, namely as Triptych August 1972 (1972), it is joined by a similarly inhuman form in the left panel. Together, these ghostly figures signal the gradual destruction of the self. Like much of Bacon’s œuvre, the triptych is sure to avoid narrative incident; however, visual cues hailing the literary origins of the pieces are present. For example, in the first tragedies’ first act, Clytemnestra lays red robes down for her husband, Agamemnon, upon his return from Troy. These same robes are alluded to in the central panel, assuming the form of a crimson-coloured framing device.

Michael Peppiatt, Bacon’s biographer, argues that the figures visible in the triptych are corporeal figurations of the deep unease of Bacon’s conscience; also present therefore, Peppiatt argues, is a sense of the deep trauma inflicted upon Bacon by his violent father, who rejected him for his homosexuality. Bacon would often remark that the ‘Furies’ – a trio of goddesses sometimes referred to as the Eumenides, who act as the instruments of justice – would ‘visit’ him on a day-to-day basis. Characters that feature in the final part of The Oresteia, their depiction suggests that beyond Bacon’s long held feelings of guilt surrounding the death of Dyer, he was still plagued by bad memories of his childhood even at this late stage in his career.