Who Did Francis Bacon Depict? A Guide to Francis Bacon’s Muses

After Second Version Of The Triptych 1944 (right panel) © Francis Bacon 1988

After Second Version Of The Triptych 1944 (right panel) © Francis Bacon 1988

Francis Bacon

58 works

Key Takeaways

Francis Bacon’s art is deeply intertwined with the lives of the people closest to him, whose presence went beyond mere inspiration, and played a critical role in shaping his intense depictions of the human condition. Bacon's portraits, influenced by his personal relationships, transformed rivalry, admiration, and volatile love into richly complex works. His muses were more than just subjects; they were catalysts for Bacon's exploration of pain, vulnerability, and identity.

Francis Bacon's body of work is a profound exploration of the human figure, delving into the depths of emotion, suffering, and psychological complexity. Known for his visceral and often unsettling depictions, Bacon revolutionised portraiture by capturing the raw intensity of the human condition. His artistic legacy is closely tied to his portrayals of key figures in his life, who were not merely passive subjects, but active participants in his exploration of vulnerability, anguish, and identity. From his competitive friendship with Lucian Freud, to his tragic love affair with George Dyer, the individuals in Bacon's life profoundly shaped his figurative work, reflecting the complex relationships that underpinned these connections.

Lucian Freud: The Complex Relationship of Two Titans

Bacon’s Portraits of Lucian Freud

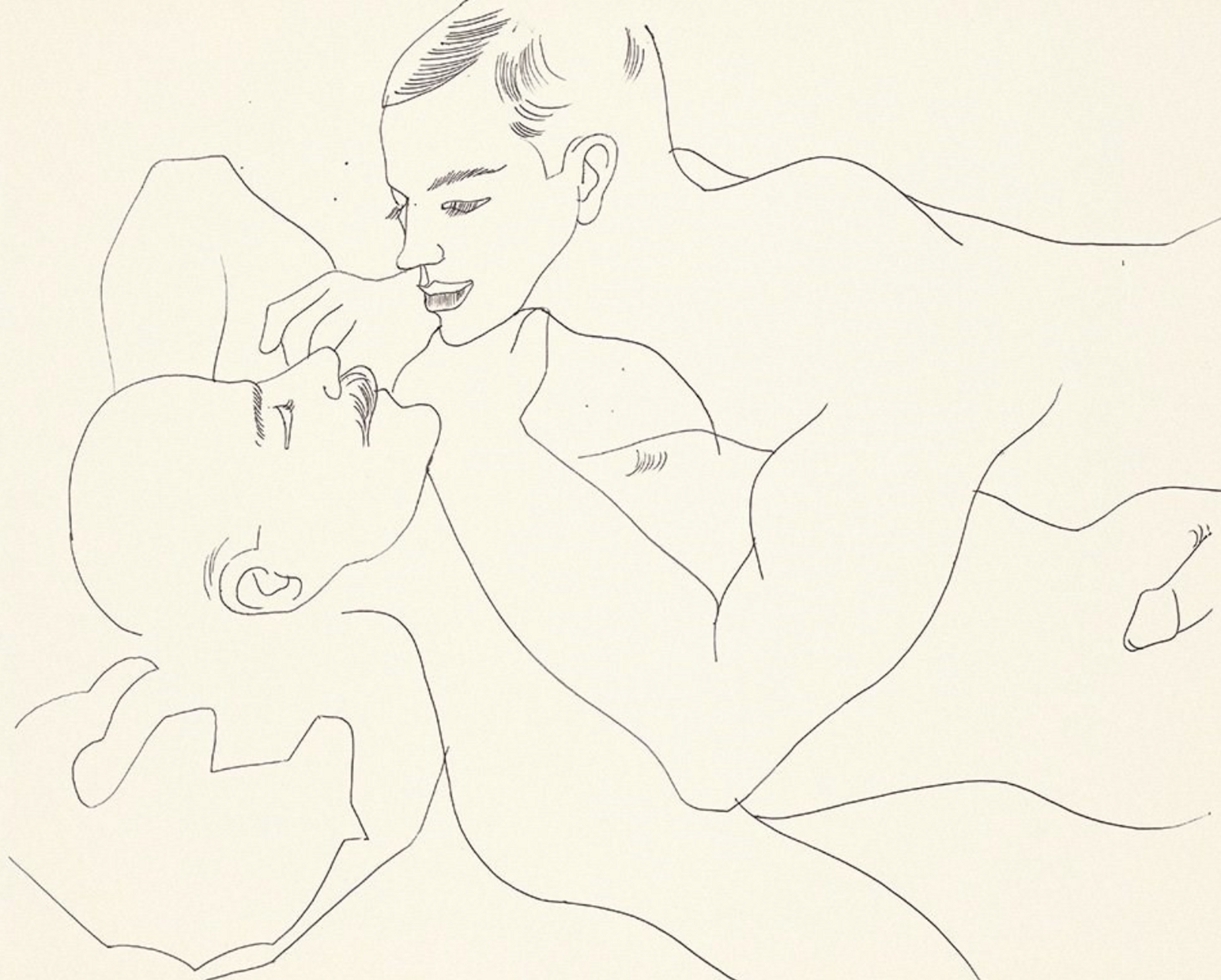

The relationship between Bacon and Freud was marked by admiration, creative tension, and profound mutual influence. Both artists were giants of 20th-century British art, and their friendship fueled both artistic inspiration and rivalry, pushing each to explore the depths of human experience in their work. Bacon’s portraits of Freud are among his most emotionally charged, capturing Freud not just as a fellow artist, but as a complex, multifaceted individual grappling with inner turmoil and existential struggles.

One of the most renowned works from this dynamic is Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969), a triptych that presents Freud in a fragmented and dynamic pose, caught between movement and stasis. The painting is celebrated not only for its technical brilliance, but also for the psychological depth it conveys, portraying Freud with a sense of vulnerability and tension. The influence of this work was recognised on a global scale when it set an auction record, selling for £108 million, a testament to its lasting impact and Bacon’s ability to capture the emotional intensity of his closest relationships. This iconic piece symbolises the complex interplay of friendship, competition, and creative energy that defined Bacon and Freud’s connection.

Their Influence on Each Other

Bacon and Freud deeply influenced one another’s artistic journeys, particularly in their shared focus on portraiture. Freud’s meticulous attention to detail, especially in rendering the human body, encouraged Bacon to push his own exploration of the physical and psychological complexities of his subjects. Conversely, Bacon’s bold, distorted figures and exploration of existential torment helped Freud move away from traditional portraiture. Bacon's work was a testament to the darker, more primal forces at play within human existence, something that resonated deeply with Freud.

George Dyer: Bacon’s Most Personal Muse

Dyer’s Impact on Bacon’s Art

George Dyer, Bacon's lover and most frequent muse, occupies a central place in the artist’s oeuvre, appearing in over forty paintings. Their relationship, which began in 1963, was stormy, passionate, and ultimately tragic. Bacon’s paintings of Dyer are infused with a sense of vulnerability, muscularity, and romantic torment, reflecting both the intensity of their bond and the darker undercurrents of their love.

In works such as Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968) and Study for Portrait (1981), Dyer is presented as a figure teetering between seduction and despair. Bacon’s portrayal of Dyer is monumental in scale and emotional gravitas. The final painting Bacon executed of him, Study for Portrait, is a culmination of these emotions, presenting Dyer in a haunting yet tender light.

Dyer’s Suicide and the Mourning Triptychs

Dyer’s suicide in 1971 left a profound mark on Bacon, leading to a series of works known as the ‘mourning triptychs’. These pieces, including Triptych May-June 1973, capture Bacon’s deep sense of loss and guilt, confronting the moment of Dyer’s death with unflinching intensity. In these paintings, Bacon confronts the fragility of human existence, his grief rendered palpable through his masterful command of form and colour.

John Edwards: Bacon’s Close Companion in His Later Years

A Lasting Friendship

In the later years of Bacon’s life, John Edwards became the artist’s closest companion. Their relationship was platonic, yet emotionally rich, and Edwards quickly became one of the most important figures in Bacon’s personal and artistic life. Bacon’s depictions of Edwards are softer, more introspective, reflecting the emotional depth of their bond, and Portrait of John Edwards (1988) is a notable example of Bacon’s more tender approach to portraiture. In contrast to the brutal intensity of his earlier works, this painting reveals a contemplative side of Bacon, portraying Edwards with warmth and vulnerability.

Edwards as Bacon’s Heir

After Bacon’s death in 1992, Edwards inherited the majority of his estate, becoming the principal custodian of Bacon's artistic legacy. This role placed Edwards at the centre of ensuring that Bacon's revolutionary contributions to modern art were properly preserved and celebrated. His stewardship went beyond the simple inheritance of artworks; Edwards took an active role in managing Bacon's vast collection, archives, and personal belongings. He worked closely with galleries, curators, and art historians to organise major retrospectives and exhibitions, notably facilitating the transfer of Bacon’s studio to the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin. This studio, painstakingly reconstructed, has provided invaluable insight into Bacon’s creative process and remains a focal point for scholars and enthusiasts alike. Through these actions, Edwards safeguarded not only the physical remnants of Bacon's work, but also his enduring legacy as one of the 20th century’s most significant and provocative artists.

Pope Innocent X: Bacon’s Obsession with Velázquez’s Masterpiece

The Velázquez Influence

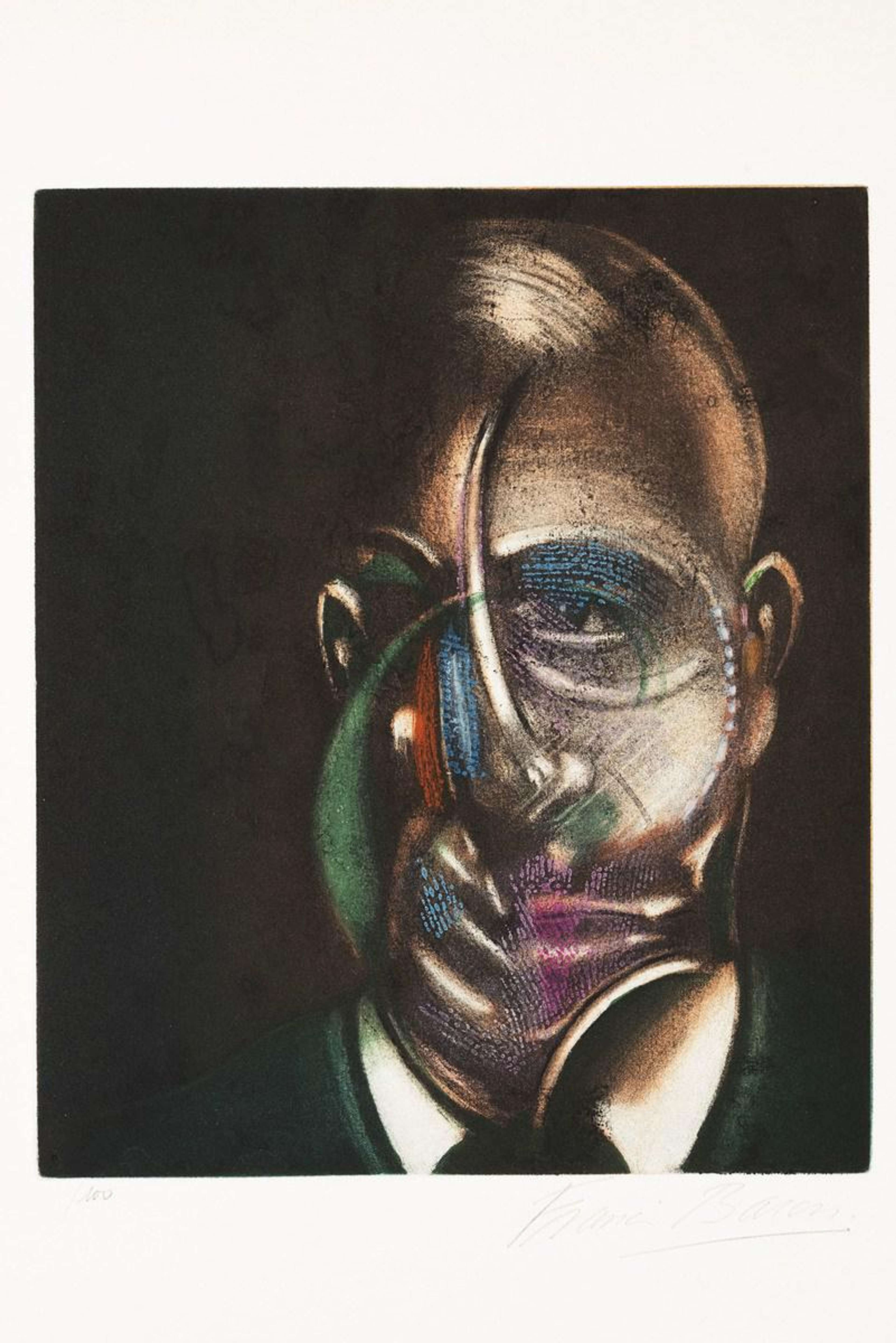

Bacon’s depictions of popes, particularly his reinterpretation of Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650), represent a profound transformation of religious icons into symbols of power, authority, and human suffering. Bacon was drawn to the image of the pope not for its religious connotations, but for what it represented; the paradox of immense power juxtaposed with the vulnerability of the human condition. The series, often referred to as the ‘Screaming Popes’, captures the internal torment and existential agony that Bacon perceived beneath the surface of these figures of authority. In Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953), Bacon transforms the serene, dignified image of the pope from Velázquez’s masterpiece into a distorted figure locked in a silent, agonised scream.

Symbolism of the Pope Figure

Through his signature frenzied brushwork and the use of dark, oppressive colours, Bacon heightens the emotional intensity, turning the pope into a haunting metaphor for suffering and despair. Bacon’s popes are often trapped within cage-like structures or veils of colour, suggesting entrapment not just physically, but psychologically, conveying a sense of isolation and torment that extends beyond the individual to the human condition at large. By reworking Velázquez’s image, Bacon was able to explore post-war themes of fear, mortality, and the failure of institutions to protect humanity.

Furthermore, Bacon’s ability to take a revered religious icon and reshape it into an image of terror and anguish not only defied traditional artistic depictions of authority, but also pushed the boundaries of how religious and historical figures could be interpreted in modern art. His ‘Screaming Popes’ stand as some of the most evocative and unsettling representations of the human experience, offering a radical reinterpretation of both religious imagery and the role of authority in contemporary culture.

Michel Leiris: The Influence of a Writer and Intellectual

An Intellectual Exchange

French writer and ethnographer Michel Leiris was one of Bacon’s closest intellectual companions. Their friendship, rooted in existential and philosophical discussions, influenced Bacon’s views on the human condition and his approach to art. Leiris’ influence on Bacon’s thinking is palpable, even though he was not as frequent a subject in Bacon’s portraits.

Leiris as a Subject

Leiris did appear in some of Bacon’s later works, including Study for Portrait (Michel Leiris) (1978), which captures the emotional and intellectual depth of their friendship. Leiris also played a crucial role in interpreting Bacon’s work, producing a monograph on the artist, titled Francis Bacon: Face et Profile, that cemented their mutual respect.

Peter Beard: The Wild Spirit in Bacon’s Circle

Beard’s Connection to Bacon

Peter Beard’s connection to Bacon extended beyond mere friendship; it was rooted in a shared fascination with the raw, primal aspects of life. Beard, an American photographer and artist known for his work documenting African wildlife, lived a life that was attractive to Bacon; immersed in nature, adventure, and danger. His raw persona mirrored many of the themes that captivated Bacon in his own work; the intensity of existence, the chaos underlying human experience, and the intersection between beauty and brutality. This wild energy resonated with Bacon, who often sought out individuals who embodied extremes, as it aligned with his own artistic explorations of violence, suffering, and existential crisis.

The discovery of over 200 of Beard’s photographs in Bacon’s studio after his death is a testament to the lasting influence Beard had on the painter. These photographs, often of animals in the wild, were visual prompts for Bacon’s creative process. Beard’s images captured life in its most untamed state, and these themes paralleled the psychological intensity and visceral quality of Bacon’s art. Bacon, who frequently used photographs and other visual references in the creation of his paintings, likely found inspiration in Beard’s documentation of the harsh realities of the natural world, which reflected his own brutal, often violent, approach to the human form.

Beard in Bacon’s Art

Though Beard did not feature as prominently in Bacon’s portraits as some of his other muses like Dyer or Edwards, his distinctive facial features and charismatic presence did inspire several of Bacon’s works. Beard’s sharp, angular face was a perfect fit for Bacon’s style of portraiture, which often sought to distort and exaggerate physical features to capture the inner complexity of his subjects. The relationship between the two men is a key example of Bacon’s attraction to unconventional figures who lived life often in extreme and dangerous ways.

Bacon’s muses were far more than just passive subjects; they were integral to his exploration of the human condition, reflecting the complex interplay between personal relationships and creative expression. Whether through his intense rivalry with Freud, his tragic love affair with Dyer, or his deep friendship with Edwards, Bacon’s portraits reveal the emotional and psychological depths of those closest to him. Each figure offered Bacon a lens through which to investigate themes of suffering, identity, and vulnerability. Ultimately, his muses were not merely inspirations but collaborators in his lifelong examination of the raw intensity of existence, helping to cement his legacy as one of the most profound artists of the 20th century.