How Does Francis Bacon Create His Art? A Guide to Francis Bacon’s Techniques

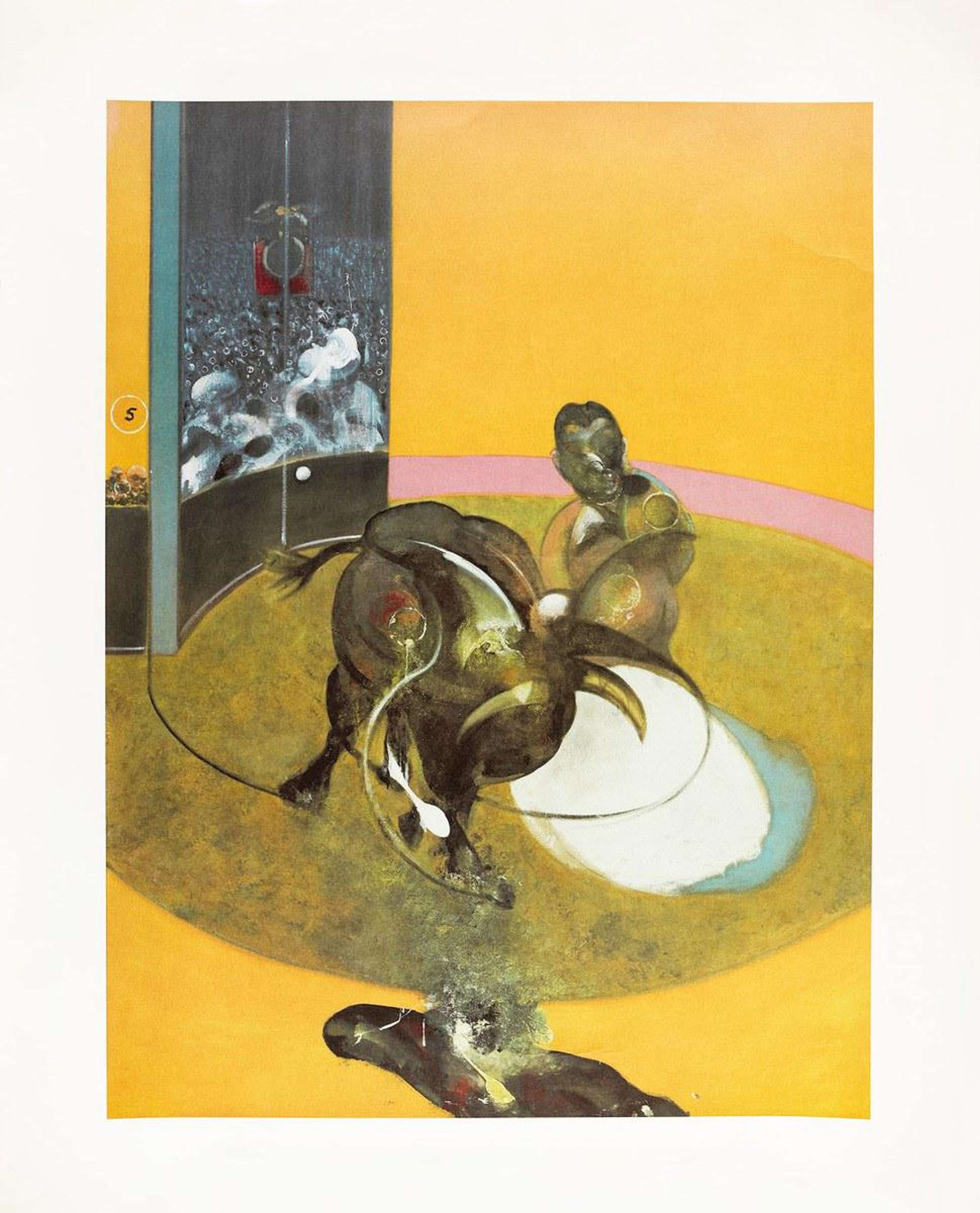

Three Studies Of The Human Body (central panel) © Francis Bacon 1980

Three Studies Of The Human Body (central panel) © Francis Bacon 1980

Francis Bacon

58 works

Key Takeaways

Francis Bacon is renowned for his intense, emotionally charged depictions of the human condition. His unique artistic techniques combined oil painting, photography, and distortion to create powerful, unsettling imagery that conveyed themes of suffering, mortality, and conflict. Bacon's process embraced chaos, spontaneity, and risk-taking, and by manipulating textures and forms, he pushed the boundaries between abstraction and figuration. His innovative use of materials and the disorderly environment of his studio reflected his deep exploration of existential themes, making his art a visceral expression of life's fragility and violence.

Francis Bacon stands as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century, revered for his brutal depictions of the human condition. His canvases evoke primal emotions, filled with violent, contorted figures that reflect the fragility and chaos of post-war existence. Bacon's work delves deep into psychological and emotional landscapes, often shocking viewers with its raw, visceral power. His disturbing yet hauntingly beautiful figures are disfigured, trapped in existential anguish, conveying themes of suffering, mortality, and conflict.

What sets Bacon apart is his unique combination of techniques; his manipulation of oil paints, his fascination with photography, and his embrace of distortion. His use of unconventional materials and methods, including his chaotic studio environment, allowed him to push the boundaries of traditional painting. Bacon’s art is not merely about representation, but about conveying the violent intensity of life itself, often drawing on the tension between abstraction and figuration.

Oil Painting and Bacon’s Command of Texture

Oil on Canvas

Bacon primarily painted in oils, a traditional medium that he bent to his will with extraordinary intensity. Using oil on canvas allowed him to build up thick layers of paint, which he manipulated to create dense, unsettling textures. His approach to painting was often erratic, spontaneous, and instinctual. Bacon worked chaotically, not aiming for precision but for raw energy. He applied the paint using stiff brushes, palette knives, and even rags, which gave his canvases an abrasive, aggressive quality.

His paintings were not about the beauty of paint smoothly applied; rather, they were about the inherent tension between different textures. Some areas would be smoothly painted, while others were rough and heavily worked, creating a striking contrast. This allowed him to juxtapose moments of calm with bursts of violence, capturing the intensity of human emotion. Bacon admired old masters like Diego Velázquez and Rembrandt for their mastery of oil paint and its texture, but he took this tradition and pushed it into more chaotic and disturbing territory.

Oil paint, with its rich texture and versatility, is particularly suited to capturing the tactile essence of flesh, especially in the depiction of meat. This quality is exemplified in Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox, where thick, loose brushstrokes evoke a visceral, fleshy quality, rendering the sensation of raw meat with a technique that anticipated the work of later Post-Impressionists. Rembrandt’s visible, unblended brushwork in this painting is a deliberate choice—he allows the paint to be the image. The texture and suppleness of the oil convey the sensation of flesh in a way that photography, even with its precision, could never fully achieve.

This ability to blend the image with the physical properties of paint was highly appealing to Bacon, especially in an era when photography had largely overtaken the illustrative role of painting. Bacon admired artists who mastered this unique characteristic of oil paint and their ability to convey form and emotion through their brushstrokes. Bacon saw this technique as critical to creating a “complete interlocking of image and paint”, where the paint itself becomes inseparable from the form it depicts. In his essay on Matthew Smith, Bacon wrote about this fusion of technique and image, emphasising how each movement of the brush reshapes and deepens the meaning of the painting.

For Bacon, this mastery of oil paint also addressed two of the greatest challenges faced by modern painting; the rise of photography and the dominance of abstraction. While photography excelled in documenting reality, Bacon believed that painting could deliver a more immediate and visceral experience by distorting and reinterpreting forms, pushing the boundaries of emotion and sensation. This idea was especially important in an art world shifting towards Abstract Expressionism, which Bacon largely dismissed. Unlike Pollock and Rothko, whose works Bacon criticised as overly decorative, he saw the future of painting as rooted in the depiction of the human figure, where the power of oil paint could evoke deeper, more complex emotions.

Bacon's work often blended photographic realism with the physicality of paint. He relied heavily on photographs, drawing inspiration from a wide array of sources, from Eadweard Muybridge's studies of movement to medical textbooks, which he manipulated into something far more emotive and intense. He believed that simply replicating a photograph wasn’t enough; the image needed to be “twisted” to make a renewed impact on the viewer. For Bacon, painting wasn't about mere representation, but about capturing the sensation of an experience in a way that photography couldn't, through the immediacy and unpredictability of oil paint.

Accidental Techniques and Risk-Taking

Bacon's creative process embraced chance. He was notorious for allowing accidents to shape his paintings, sometimes throwing paint or manipulating it in unpredictable ways. He believed these accidents introduced an element of spontaneity that heightened the emotional impact of his work. If paint splattered or dripped, Bacon would work with it rather than correcting it, allowing these moments of chance to inform the final composition. This risk in painting mirrored Bacon's personal philosophy; his art was about confronting the chaos and uncertainty of life head-on, much like his love of gambling reflected his attraction to risk and unpredictability.

Bacon’s Use of Distortion and Abstraction

Manipulating the Human Figure

Bacon’s work is synonymous with distortion and abstraction, particularly in his treatment of the human figure. He was fascinated by the fragility of the body and often depicted it as if in a state of disintegration or transformation. His figures are not stable but blurred, twisted, and violently contorted, suggesting both physical and psychological trauma. These grotesque figures express an intense exploration of mortality, flesh, and decay, influenced by his experience of war and his bleak view of humanity.

Bacon would typically start with a fairly realistic depiction of a figure but then distort it, either by wiping away parts of the paint with a rag or physically manipulating the paint while still wet. This would create an unsettling sense of motion, as though the figures were caught in a moment of transformation or destruction. His work with the human form drew on traditions from the Renaissance, but where artists like Michelangelo depicted idealised, heroic figures, Bacon’s subjects were often brutalised and deformed, as if caught in a painful, unending metamorphosis.

Figures in Isolation

A recurring motif in Bacon's work is the isolation of his figures in stark, geometric spaces. He often placed his distorted subjects within cage-like structures or boxed them into confined spaces, which emphasised their sense of alienation and entrapment. This technique, known as ‘spaceframes’, became a signature of his work and added to the claustrophobic, existential dread of his paintings. These geometric enclosures symbolised both physical and psychological imprisonment, forcing viewers to confront the anguish of the figures within.

Bacon’s Approach to Printmaking: Etching and Lithography

Bacon's Exploration of Printmaking

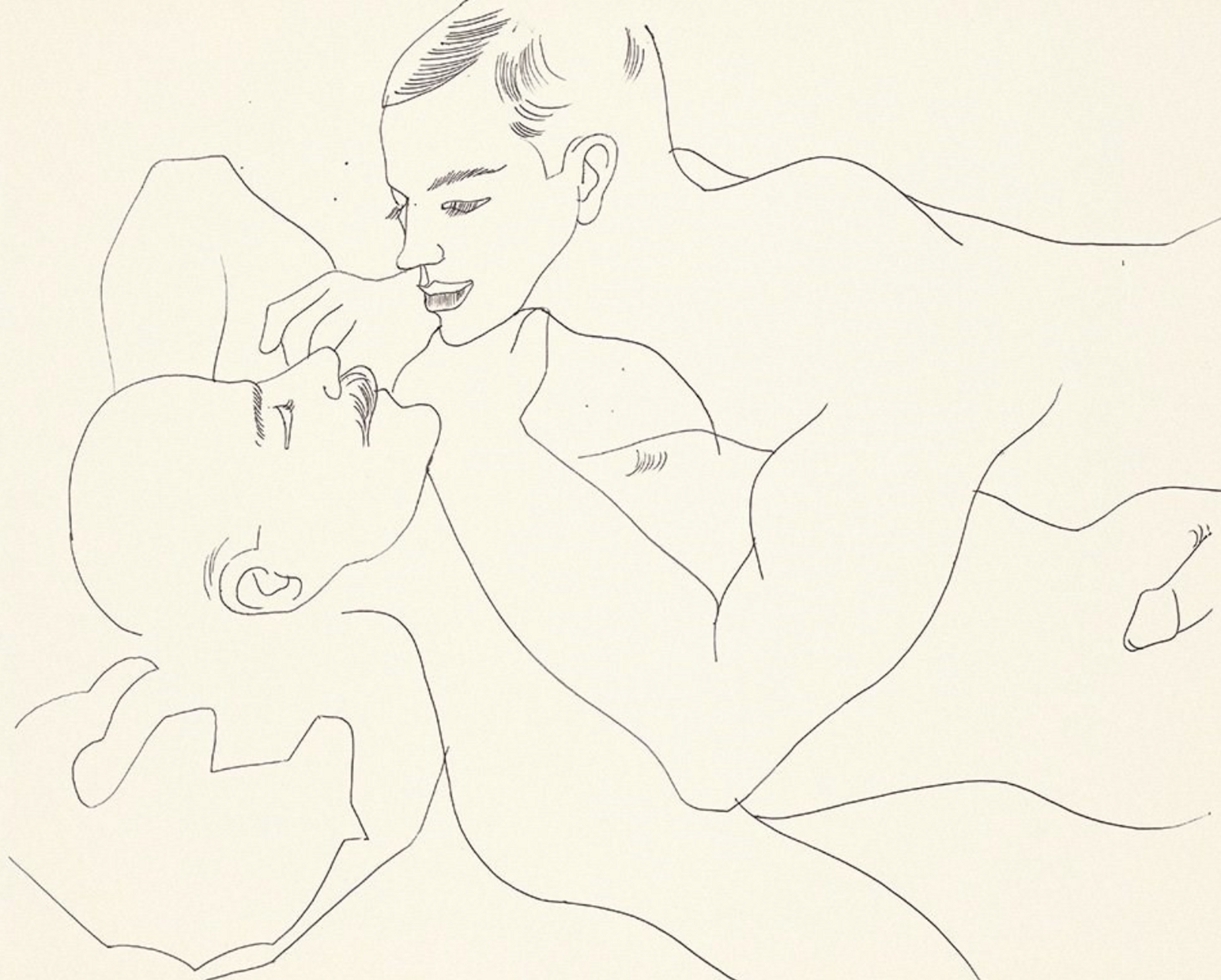

Bacon's approach to printmaking was deeply intertwined with his painting techniques, emphasising texture, distortion, and emotional intensity. Though he primarily focused on painting, Bacon's prints retained the raw power and immediacy of his canvases. He often worked with master printmakers, using methods like lithography and etching to translate his visceral, distorted figures into prints. Bacon’s prints, like his paintings, explored the tension between figuration and abstraction, using bold lines and rich tonal contrasts to create haunting, dynamic images. His prints were not mere reproductions, but standalone works that captured the violent energy and psychological depth characteristic of his art.

Etching Techniques: Retaining Intensity in Print

Bacon’s etchings maintained the raw power of his paintings by using a metal plate etched with acid to create deep lines that were then filled with ink. His use of etching allowed for a dynamic interplay between light and dark, with bold contrasts enhancing the drama and violence inherent in his subjects. Prints such as Study for a Portrait of John Edwards show his meticulous attention to preserving the darkness and distortion that permeated his paintings, ensuring that the emotional weight carried through from canvas to print.

Study For A Portrait Of Pope Innocent X © Francis Bacon 1989

Study For A Portrait Of Pope Innocent X © Francis Bacon 1989The Role of Photography and Visual References in Bacon’s Process

Influence of Photography

Photography was central to Bacon’s creative process, as he often worked from photos rather than live models. He kept an extensive and disorganised archive of reference materials, including crime scene photos, medical textbooks, and images torn from magazines. Many of these images were distorted, crumpled, or stained with paint, reflecting Bacon’s interest in reworking and transforming mundane imagery into something charged with existential meaning.

He was particularly influenced by Muybridge's photographic studies of motion, which captured the human body in various stages of movement. These sequential images inspired the dynamic, distorted figures that populate Bacon’s paintings, as they freeze the body in moments of flux, decay, and violence.

Repetitive Imagery

Bacon frequently reused the same photographic references across multiple works, obsessively revisiting certain images. One famous example is his series of Pope paintings, which were all based on Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X. Bacon distorted this portrait into a grotesque figure, screaming and trapped within a cage, turning a symbol of religious authority into one of existential terror.

Bacon’s Unconventional Studio and Working Environment

A Chaotic Studio

Bacon’s studio at 7 Reece Mews in London was legendary for its chaos. The space was overflowing with torn photographs, paint splatters, books, and discarded materials. This chaotic environment mirrored his working method, in which disorder and spontaneity were crucial to the creative process. His studio was not just a workspace, but a reflection of the turmoil and intensity that informed his art. Today, the studio has been reconstructed at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, offering a glimpse into the mind of the artist.

Despite the apparent disorder, Bacon had a methodical approach to certain aspects of his process. He meticulously prepared his canvases by priming them with white paint, allowing his oil colours to stand out more vividly. While his working environment was chaotic, his technique involved a careful balance between control and spontaneity.

Bacon’s art remains a powerful exploration of the human condition, rendered through a blend of chaotic and controlled techniques. His spontaneous approach to oil painting, distortion and photographic references, all contributed to the visceral intensity of his work. Bacon’s art does not merely represent life; it confronts its darkest, most primal aspects, offering an unsettling reflection on the human experience. Bacon's legacy endures as one of psychological realism, capturing the instability, fragility, and violence of human existence in ways that continue to resonate with contemporary artists. His work remains an uncompromising exploration of beauty and torment, pushing the boundaries of what art can communicate about the depths of human emotion.