The Influence of Francis Bacon on David Lynch’s Filmmaking

Image © flickr / David Lynch © 2007

Image © flickr / David Lynch © 2007

Francis Bacon

58 works

Key Takeaways

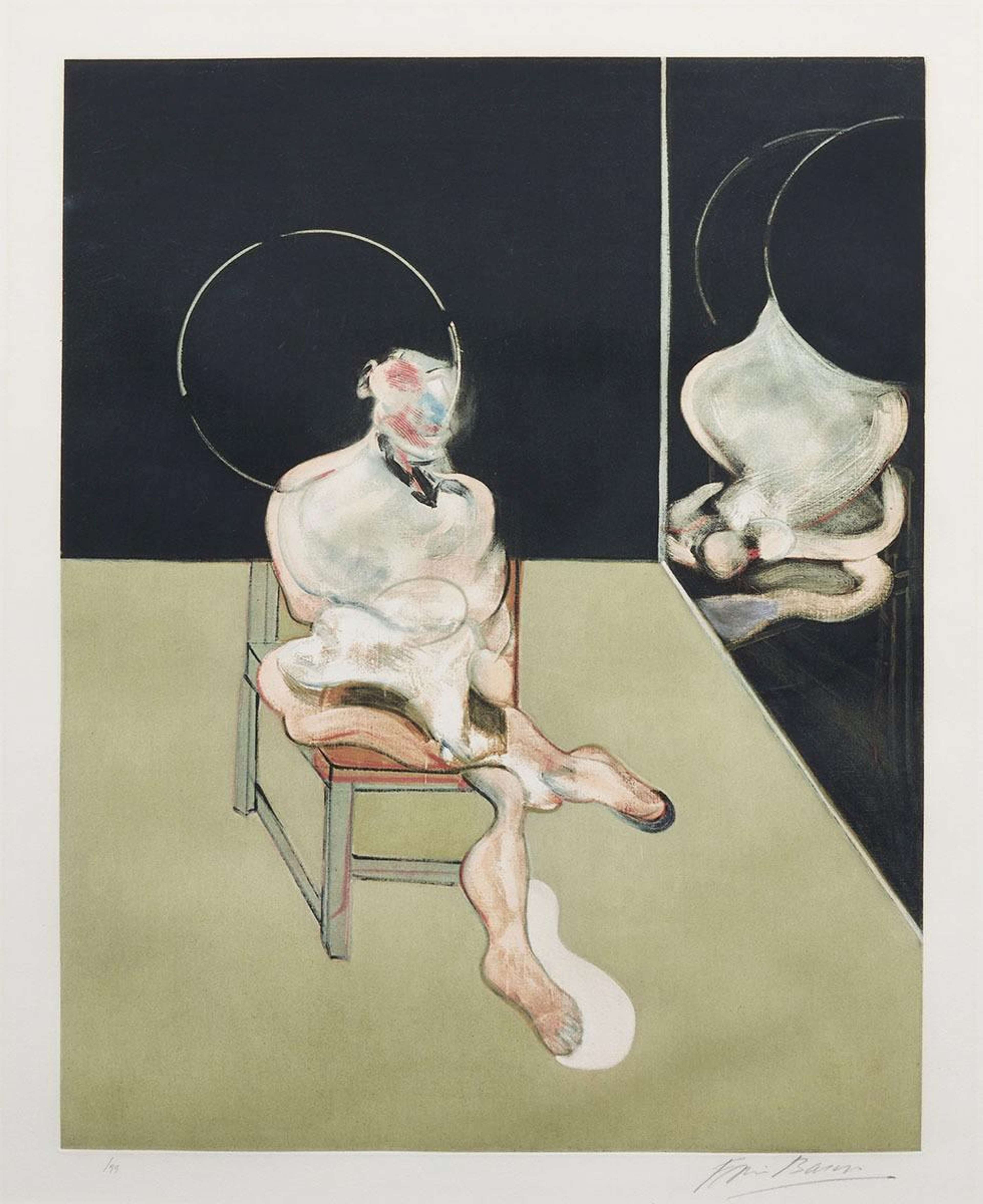

Francis Bacon’s visceral art and David Lynch’s surreal films share a profound, unsettling aesthetic, where human vulnerability, psychological horror, and bodily distortion blend into powerful, introspective images. Lynch’s cinematic worlds draw inspiration from Bacon’s claustrophobic, distorted spaces and anguished figures, reinterpreting the emotions of Bacon’s paintings into cinematic form. Both artists use surrealism and horror not just to shock, but to expose the fragility inherent in the human experience, probing existential themes that lay bare the beauty within horror, and the horror within beauty.

In the feverish visions of Francis Bacon and David Lynch, reality splinters, exposing a world where beauty and horror collide in grotesque harmony. Lynch’s universe borrows from Bacon’s twisted depictions of flesh and fractured psyches, distilling his paintings’ existential despair into unsettling cinematic form. Characters in Lynch’s work drift through spaces that echo Bacon’s claustrophobic voids, embodying a sense of dread that feels both surreal and hauntingly familiar. The threads binding these two visionaries, from Lynch’s distorted, dreamlike bodies and Bacon’s unsettling spatial geometry, probe the darker recesses of the human soul with unflinching curiosity.

The Shared Aesthetic Between Francis Bacon and David Lynch

Bacon and Lynch are two artists from distinct mediums, yet their shared exploration of human vulnerability, psychological horror, and bodily distortion binds their work with a unique, visceral aesthetic. Bacon’s paintings are studies in unease, his canvases dominated by twisted, fleshy figures, often set against claustrophobic backdrops that intensify a sense of confinement and anguish. Lynch’s cinematic landscapes echo this oppressive atmosphere, where characters and environments blur into one another, creating worlds that reflect inner turmoil and existential dread. Both artists confront the viewer with a world that feels as menacing as it is mesmerising, where the lines between the familiar and the horrific dissolve.

Bacon and Lynch possess a shared ability to turn beauty into terror, drawing us into a surreal realm that probes the fragility of human existence. Rather than merely mimicking Bacon’s aesthetic, Lynch translates Bacon’s principles - tension, isolation, and the unspoken disturbances of the subconscious - into the language of cinema, creating his own visual dialect that is both an homage to Bacon and a distinct exploration of darkness in its own right. Together, they shape a narrative where human existence is as fragile as it is defiant.

The Influence of Bacon’s Distorted Figures on Lynch’s Cinematic Characters

The Vulnerable Human Body

Philosopher Gilles Deleuze explores Bacon’s work in Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, arguing the human form becomes a battleground of agony and disarray, a raw spectacle of existential suffering. In paintings like Study for a Portrait and Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Bacon’s figures are twisted and compressed, their bodies contorted beyond anatomical limits as if to visually capture the depths of human despair and vulnerability. These distorted figures embody an unfiltered torrent of pain, becoming visceral symbols of the inexpressible torment within. Bacon’s choice to exaggerate and distort the body so brutally invites viewers into an unflinching contemplation of human fragility and a sense of anguish that defies containment. Here, the flesh itself becomes a vessel for the inner turbulence of the soul, where suffering is unflinchingly externalised.

Echoes of Bacon’s Figures in Lynch’s Film Characters

Lynch draws deeply from this disturbing visual lexicon, crafting characters that evoke Bacon’s tortured bodies, embedding them with a haunting sense of deformity and psychological imprisonment. In Eraserhead (1977) and The Elephant Man (1980), Lynch’s protagonists embody an almost Baconian sense of the grotesque and the vulnerable. Henry, the protagonist of Eraserhead, becomes an emblem of existential dread, his haunted, silent suffering reminiscent of Bacon’s spectral figures, while John Merrick in The Elephant Man reveals the despair of a body and soul outcast by society. These characters bear Lynch’s cinematic reinterpretation of Bacon’s distorted forms, each figure portraying an agony that is both visible and psychological, often hovering between reality and nightmare.

Lynch does more than pay homage; he channels Bacon’s strategy of using the body as a site of trauma and isolation, giving his characters an embodied torment that pulses on screen. Through Lynch’s lens, physical deformity merges with emotional alienation, and his characters become canvases onto which their inner struggles are projected, much like Bacon’s fractured bodies. In their work, the line between the body and mind is blurred, exposing a psychological realism that confronts the depths of despair, resilience, and the terrifying beauty of our own fragility.

The Use of Space and Atmosphere: Creating Unsettling Environments

Bacon’s Claustrophobic Spaces

Bacon’s paintings confront viewers with spaces that feel less like rooms and more like psychological cages, environments so oppressive they seem to swallow his figures whole. Figures are often placed inside geometric cages or against backdrops that merge into indeterminate spaces, evoking a visceral feeling of existential dread. Bacon’s use of enclosing structures serve as psychological projections, inviting viewers to confront isolation and agony through the unforgiving confines of the subject's settings.

Lynch’s Cinematic Worlds and the Influence of Bacon’s Spaces

Much like Bacon’s unsettling enclosures, Lynch’s spaces are not merely settings; they are states of mind, constructed to reveal the fears and secrets of his characters. Lynch channels the disturbing, claustrophobic energy of Bacon’s worlds into his own surreal, cinematic landscapes. Films like Blue Velvet (1986) and the eerie world of Twin Peaks create their own spatial prisons - rooms, towns, and empty spaces - that isolate characters as effectively as Bacon’s canvases. Lynch’s sparse, hyper-controlled environments, from the cold industrial backdrops in Eraserhead to the shadow-filled rooms of Mulholland Drive (2001), are laden with a sense of mystery and menace. His characters often inhabit liminal spaces that echo Bacon’s oppressive frames, amplifying the feeling of psychological entrapment. These settings evoke unease and disorientation, stripping away any illusion of comfort or escape.

Themes of Horror and the Grotesque: From Canvas to Cinema

Bacon understood horror as something deeply embedded in the psyche, using grotesque exaggeration to shatter the veneer of civility, exposing what lies beneath. His art is a confrontation with horror at its most unfiltered, plunging into the visceral and grotesque to strip the human condition to its core. His paintings do not merely depict horror; they embody it, presenting distorted bodies and agonised expressions that seem to scream out from the depths. In works like Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Bacon captures the terror not only of physical pain but of psychological disintegration, as flesh appears to melt, twist, or cage itself in an unending cycle of torment. He invites viewers to witness the grotesque in a way that goes beyond revulsion, drawing us into an aesthetic of horror that is both captivating and profoundly unsettling.

Where Bacon’s canvases present static moments of horror, Lynch’s films take this horror and animate it, extending it into the flow of time and sound, where it becomes a continuous, inescapable experience. Lynch’s portrayal of horror doesn’t aim for gore, but instead for a surreal, dreamlike intensity that makes fear almost beautiful, plunging audiences into what feels like a dark, twisted meditation on the human psyche. Through this transformation, Lynch echoes Bacon’s ability to make horror both haunting and irresistible, inviting viewers not to run from fear, but to become intimate with it. By drawing viewers into worlds where the grotesque is both familiar and alien, Lynch expands Bacon’s aesthetic into an immersive experience, where horror becomes a language of its own. In doing so, Lynch doesn’t just inherit Bacon’s horror; he makes it his own, turning the surrealist grotesque into a medium of cinematic poetry.

Surrealism and Psychological Depth: A Shared Language of Expression

Bacon’s unsettling visual language has left a lasting imprint on the worlds of surrealism, horror, and psychological cinema. Filmmakers, including Christopher Nolan and Ridley Scott, have drawn upon his vision to explore psychological depths and surreal landscapes. Nolan revealed that Heath Ledger’s iconic portrayal of the Joker in The Dark Knight (2008) was partly inspired by a triptych by Bacon, with the Joker’s makeup design being based on the “blurred sort of distortions” of Bacon’s painted faces. Scott’s Alien (1979) also took inspiration from Bacon; the creature bursting from a crewmember’s chest being modelled on the monstrous figures from Bacon’s 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.

The Lasting Influence of Bacon on Lynch’s Legacy

Lynch openly credits Bacon as a formative influence, recognising Bacon’s exploration of the human emotion as a defining touchstone for his own work. In an interview with Cahiers du Cinéma, Lynch expressed admiration for the intensity with which Bacon captures the essence of psychological torment and physical vulnerability, an intensity Lynch sought to evoke in his own films. For Lynch, Bacon’s legacy is not only an artistic inheritance, but a continual point of inspiration, one that fuels his exploration of surrealism and existential angst on screen.