The Ultimate Guide to Jean-Michel Basquiat: A-Z Facts

Rome Pays Off © Jean-Michel Basquiat 2004

Rome Pays Off © Jean-Michel Basquiat 2004

Interested in buying or selling

Jean-Michel Basquiat?

Jean-Michel Basquiat

59 works

Iconic Neo-expressionist artist Jean-Michel Basquiat used his raw, graffiti-influenced art to delve into themes of race, identity and social tension.

How did Jean-Michel Basquiat die? Where was he born? Here are some facts about the artist whose work captivated and challenged societal norms.

A is for Andy Warhol

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol had a unique and influential relationship, personally and professionally. The two artists met in the early 1980s and soon became close friends. Warhol – already a celebrated figure in the art world – was intrigued by the young and talented Basquiat, who was then just making a name for himself. Basquiat, in turn, admired Warhol's work and saw him as a mentor. Their relationship had a significant impact on their art, and in 1984-85, they embarked on a series of collaborative works that sparked considerable discussion. While some critics dismissed these works, others saw in them an intriguing fusion of Warhol's pop sensibility and Basquiat's raw, expressionistic style.

The relationship was not without its tensions: as Basquiat's fame grew, so did the scrutiny of his friendship with Warhol, and some accused Warhol of exploiting the younger artist; an allegation that deeply hurt Basquiat. Despite this, their friendship persisted until Warhol's death in 1987, an event that profoundly affected Basquiat. Today, their collaborative works stand as a testament to their unique artistic dialogue and to the deep personal bond they shared. Despite the controversies and complexities of their relationship, it's clear that both artists had a significant impact on each other's lives and work.

Image © Tiffany & Co / Jay-Z and Beyoncé standing in front of Basquiat’s Equals Pi 2021

Image © Tiffany & Co / Jay-Z and Beyoncé standing in front of Basquiat’s Equals Pi 2021B is for Beyoncé and Jay-Z

In 2021, an advert for Tiffany & Co. featuring Jay-Z and Beyoncé standing in front of Basquiat’s Equals Pi drew criticism, with his former studio assistant claiming “they wouldn’t have let Jean-Michel into a Tiffany’s if he wanted to use the bathroom or if he went to buy an engagement ring and pulled a wad of cash out of his pocket.” Equals Pi uses the same robin egg blue as the iconic jewellery brand, but questions were still raised about whether the commodification of Basquiat’s work within this setting was acceptable.

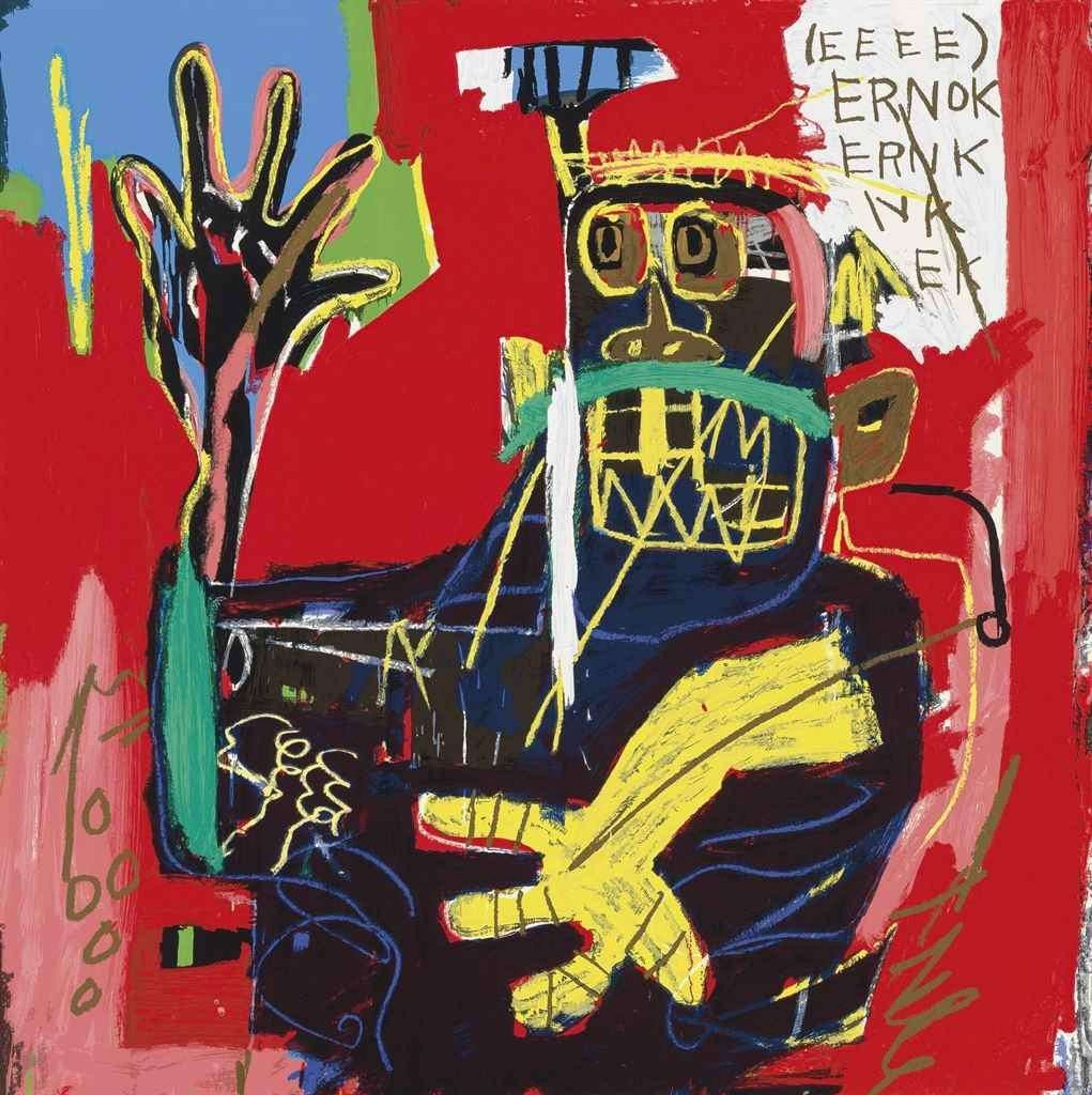

C is for Crowns

Basquiat's crown motif is one of the most recognisable elements in his art. Basquiat used the crown to celebrate black history and heritage, and it is seen as a way to honour and exalt his subjects. Some critics view the crown as a symbol of respect and reverence, declaring the figures in his paintings as kings and heroes. This can be interpreted as Basquiat asserting the value and worth of black individuals and culture, countering a society that has often marginalised them. Others see it as a critique of social power structures, an ironic commentary on the value society places on wealth and status. In this interpretation, Basquiat is seen as questioning who we revere and why, challenging traditional notions of who gets to be "king." In any case, the crown motif showcases Basquiat's ability to imbue simple symbols with complex, multi-layered meanings. Through these crowns, he was able to communicate potent messages about identity, status, power, and race. They have become synonymous with the artist.

Cadillac Moon © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981

Cadillac Moon © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981D is for Debbie Harris

Blondie singer Debbie Harry was Basquiat’s first patron, having purchased his painting Cadillac Moon for $200 in 1981. This marked Jean-Michel’s first sale of his art, and it came on the heels of Harry and Basquiat acting together in the movie Downtown 81. Harry said about Basquiat: “When I first met him, I think he was still a teenager. He was just going around doing his SAMO thing. We just thought he was very sort of unspoken, really. He wasn’t very verbal. Although he had brilliant ideas and could really talk, at that point he was just this kind of quiet little kid—but cute. (...) I think he tried to be deconstructive [in his fashion], in a way, and that sort of goes along with his art. He was always sort of taking things apart and minimising them.”

Eroica I © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1988

Eroica I © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1988E is for Eroica I & II

These are two large diptych paintings by Basquiat from 1988 that showcase his layered and dynamic style in his later years. The name of the paintings references Beethoven's third symphony, showing Basquiat's deep love for music.

Image © Sotheby’s / Untitled c. 1982

Image © Sotheby’s / Untitled c. 1982F is for Found Objects

Basquiat often incorporated found objects into his works, showcasing his innovative use of materials and his ability to create art from everyday items. This approach stems from his beginnings as a graffiti artist in New York City, where improvisation and the use of readily available materials were crucial. In his studio works, Basquiat often incorporated various found materials such as scrap wood, metal and paper, using them either as surfaces to paint on or as collage elements within his paintings. For instance, his early works from the 1980s often used salvaged doors, window frames, and other architectural elements as unconventional canvases. He also incorporated elements like newspaper clippings, fragments of comic books, and segments of advertisements into his works.

G is for Gray's Anatomy

Anatomical subjects play an important part in Basquiat’s work. His fascination with the subject began with his mother giving him the book Gray’s Anatomy after he suffered a car accident as a child. His interest in the subject culminated in his Anatomy series, a collection of artworks focusing on different body parts.

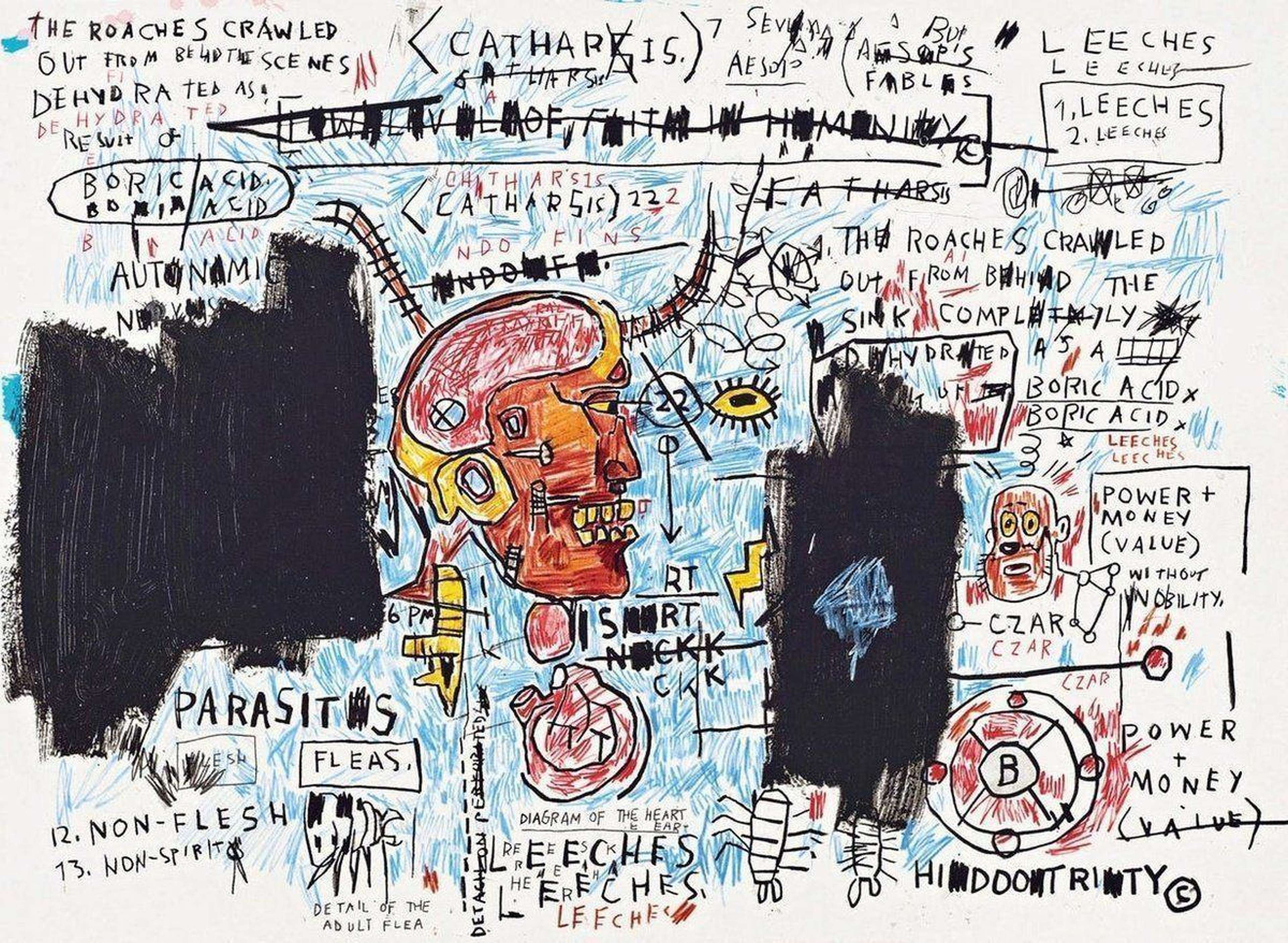

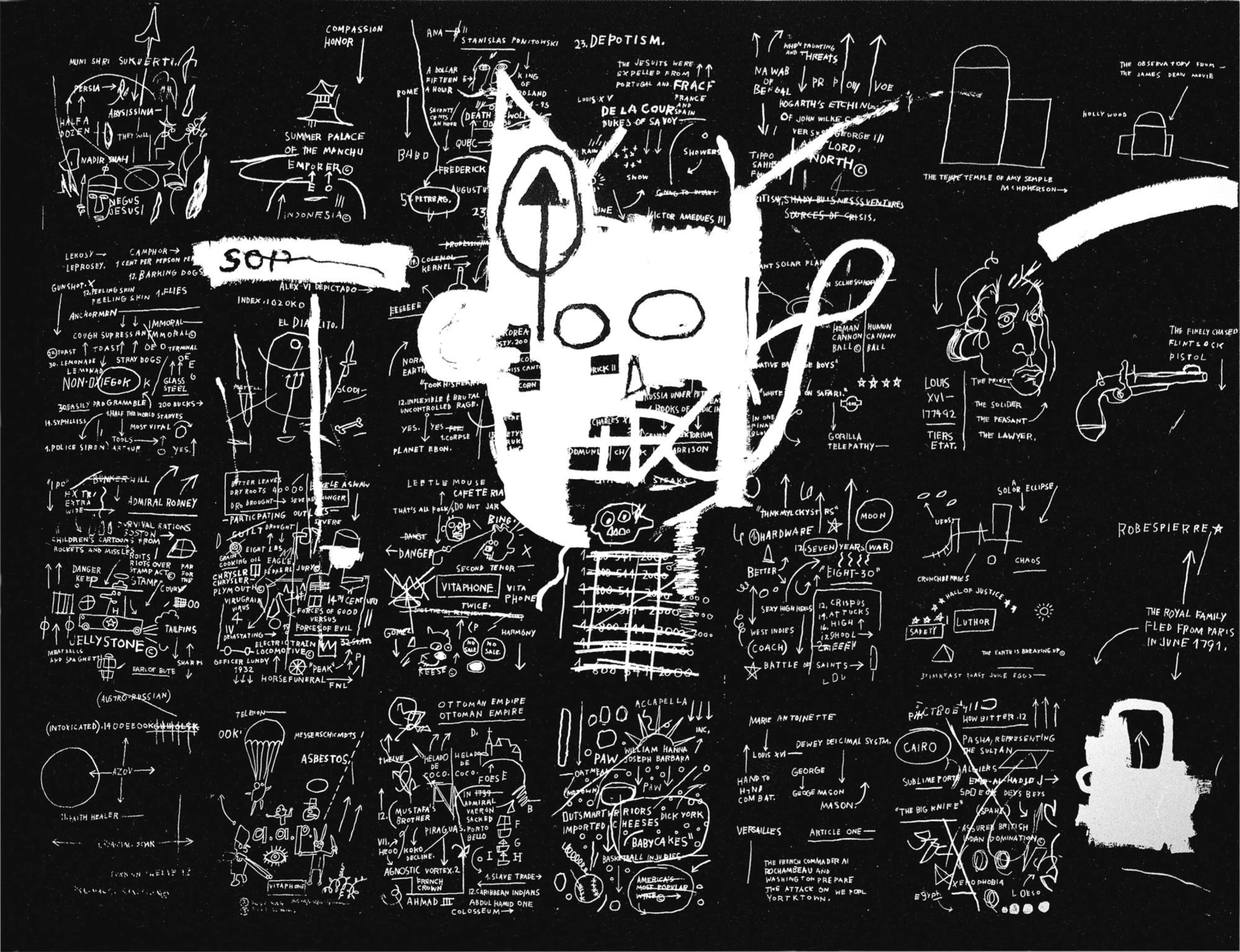

H is for Heads

Basquiat's Heads are some of the most recognised in his oeuvre. These distinctive head images, or skulls, reflect a combination of styles and influences, including African tribal masks, street art, and expressionist painting. Basquiat began creating these heads in the early 1980s, as soon as he transitioned from street art to working on canvas. The heads often appear as imposing, mask-like figures, featuring bold, expressive lines, vibrant colours, and abstract forms. In many of these works, Basquiat contrasts these raw, visceral images with text or other symbols, creating a complex interplay of elements.

I is for Inspiration

Basquiat drew inspiration from a wide array of sources. As an artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, he was deeply interested in African and Caribbean cultural heritage. He also drew heavily from his experiences as a Black man in America, exploring themes of racism, colonialism, and Black identity. Other inspirations included music, art history, anatomy textbooks and the work of other artists such as Pablo Picasso, Warhol and Cy Twombly. This rich blend of influences contributed to his unique and idiosyncratic style.

Horn Players © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1983

Horn Players © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1983J is for Jazz

Jazz played a significant role in the life and art of Basquiat. With its improvisational nature, complex rhythms and historical ties to African American culture, jazz paralleled Basquiat's own approach to creating art. His work is also characterised by spontaneity, with elements of improvisation and layers of complexity that unfold over time. In many of his paintings, Basquiat made direct references to jazz musicians. For example, in Horn Players (1983), he depicts jazz legends Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The structure of the painting mirrors the structure of jazz music, with its distinct yet interconnected sections. The figures are fragmented and abstracted, just as jazz often breaks down conventional melody and harmony.

K is for Keith Haring

Basquiat and Keith Haring were both influential artists who emerged from the vibrant downtown New York City art scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Their paths crossed multiple times, leading to a friendship and mutual artistic respect that was pivotal for both of them as they both navigated the transition from street artists to internationally recognised figures in the art world. They shared similar backgrounds in graffiti and street art, and their works both blended high and low culture, using an accessible visual language to tackle complex social and political themes.

Basquiat and Haring were known to influence each other's works. Their art was bold, colourful, and packed with symbols, and they both used their work to comment on societal issues such as race, class, and consumerism. However, their friendship went beyond their shared artistic pursuits. They were often seen at the same parties and social events, and there are many photos from the period showing them together. Their friendship continued until Basquiat's untimely death in 1988. Haring was deeply affected, and he created a series of works in tribute to his friend.

In an interview, Haring said of Basquiat’s work: “Before I knew who he was, I became obsessed with Jean-Michel Basquiat's work. The stuff I saw on the walls was more poetry than graffiti. They were sort of philosophical poems that would use the language the way Burroughs did – in that it seemed like it could mean something other than what it was. On the surface, they seemed really simple, but the minute I saw them I knew that they were more than that. From the beginning, he was my favourite artist.”

Image © Gagosian / One of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s exhibitions at Gagosian 2013

Image © Gagosian / One of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s exhibitions at Gagosian 2013L is for Larry Gagosian

Larry Gagosian is a prominent American art dealer who has been instrumental in shaping the contemporary art market. He is the founder of Gagosian Gallery, which has locations in several cities worldwide and represents some of the most significant contemporary artists and estates. In the early 1980s, when Jean-Michel Basquiat was beginning to gain recognition in the art world, Larry Gagosian became one of his dealers. Gagosian was known for his ability to spot emerging talent and his knack for promoting and selling their work – see the potential in Basquiat's raw, expressive style, he was instrumental in helping him gain wider recognition.

In 1982, Gagosian invited Basquiat to live and work in a house he rented in Venice, California, and he held Basquiat's first solo shows at his Los Angeles gallery in 1982 and 1983. These shows were pivotal moments in Basquiat's career, helping to establish him as a significant figure in the art world beyond New York City. After Basquiat's death in 1988, Gagosian continued to promote his work, and his gallery has held several major Basquiat exhibitions over the years.

M is for Museums

Jean-Michel Basquiat had a complex relationship with museums and the institutional art world. Despite being self-taught and coming from a graffiti background, his work quickly gained recognition and was included in several important exhibitions during his short life. In 1981, Basquiat was included in the "New York/New Wave" exhibition at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1), which was a significant milestone in his career. However, despite this early recognition, Basquiat often expressed frustration with the racial dynamics of the art world, including the underrepresentation of Black artists in museums.

During his lifetime, Basquiat's work was collected by major museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, but his relationship with these institutions was not always easy. For instance, the Museum of Modern Art initially rejected his work for their collection, a decision that Basquiat reportedly took personally. Following his death in 1988, Basquiat's work has been the subject of several major retrospective exhibitions, and his paintings are now held by many of the world's most prestigious museums -- the work seen above is in the collection of the MoMA, for example. This late inclusion has continued to spark discussions about representation in these institutions, reflecting larger debates about diversity and inclusivity in the art world.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / 57 Great Jones Street, Basquiat's final apartment and studio in New York.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia / 57 Great Jones Street, Basquiat's final apartment and studio in New York.N is for New York City

Basquiat's life and work were deeply intertwined with New York City, and its energy, grit, and diversity were integral to Basquiat's work. Born and raised in Brooklyn, the creative dynamism of the city greatly influenced his artistic development. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Basquiat became part of the vibrant downtown art scene. This creative community, centred around neighbourhoods like SoHo and the East Village, was a hotbed of experimental art, music and film. His art often incorporated elements of city life, including its urban landscapes, its multicultural and multilingual voices, and its social and political issues.

Basquiat was an active participant in this scene, collaborating with artists, musicians, and writers. As Basquiat's career took off, he became part of the city's high-end art market.

New York City was not only Basquiat's home but also his muse, his canvas and his stage. His art is a reflection of the city's vitality and complexity, capturing its rhythms, tensions and endless capacity for reinvention.

O is for Oil Paint Sticks

Oil paint sticks, also known as oil sticks or oil bars, were a significant part of Basquiat's artistic practice. Essentially, oil paint sticks are oil paints in solid form, packaged in a crayon-like stick. This allows artists to draw or paint directly onto a surface without the need for brushes or other tools. As Basquiat was known for his multi-layered compositions and use of varied materials, oil paint sticks fit perfectly within his approach. They allowed him to combine the immediacy and expressiveness of drawing with the richness and texture of oil paint, and he could scribble, draw or write directly onto the canvas – and then build up layers of paint around these marks.

Basquiat's use of oil paint sticks contributed to the distinctive look of his work: his lines were often bold and energetic, mirroring the intensity of his themes and ideas. The oil sticks also allowed him to incorporate written words and phrases into his paintings, a hallmark of his style. Oil paint sticks also enabled Basquiat to work quickly, which suited his spontaneous, improvisational approach to art-making. He could respond to ideas as they came to him, without the need to mix colours or clean brushes.

P is for Primitivism

An art style that Basquiat is often associated with. Despite its problematic nomenclature, primitivism refers to the fascination with and incorporation of non-Western symbols, motifs, or methods traditionally viewed as "primitive" or less refined by Western standards. This can include African, Pacific Islander, Indigenous American or Aboriginal Australian artistic traditions, among others. As an artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, Basquiat was deeply interested in African and Caribbean cultural heritage and history, often incorporating related motifs and symbols into his work. He used this primitivist style to subvert and critique Western art conventions and explore issues of race and identity.

However, it's important to note that labelling Basquiat's work as primitivist can be contentious. While it's true that his work incorporated elements traditionally associated with primitivism, some critics argue that applying this label overlooks the unique and highly personal nature of Basquiat's style and the deeply informed, critical way he engaged with his cultural heritage and the conventions of Western art history. As such, while primitivism is one lens through which we can view and interpret Basquiat's work, it's far from the whole story.

Q is for Quotes

Basquiat's paintings often quoted historical, artistic, and literary sources, including the Bible, art history, and early 20th-century literature. He has also become known for his soundbites, which provide insight into his ethos and intellect. One iconic one states: “I don't listen to what art critics say. I don't know anybody who needs a critic to find out what art is.”

Image © IMDB / The film poster for “Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child” 2010

Image © IMDB / The film poster for “Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child” 2010R is for “Radiant Child”

The term "Radiant Child" is often used in reference to Jean-Michel Basquiat due to an influential article and a documentary film that used this title. Art critic Rene Ricard first used the phrase in an essay titled "The Radiant Child" published in December 1981. This piece, one of the first major articles about Basquiat, helped bring the artist to wider attention. Ricard's description was a nod to Basquiat's youth, raw talent and the luminescent quality of his art, as well as the public's fascination with his meteoric rise from street artist to art world sensation. The phrase was later used as the title of a 2010 documentary about Basquiat, "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child," directed by Tamra Davis. The film includes rare footage of Basquiat, interviews with friends and contemporaries, and a review of his short but prolific career.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr

Image © Creative Commons via FlickrS is for SAMO©

SAMO© was a graffiti project started by Jean-Michel Basquiat and his high school friend Al Diaz in the late 1970s in New York City. The name is a contraction of "same old" (as in "same old shit"), reflecting their shared sense of disillusionment with the conventional world. The pair began writing enigmatic, poetic messages on buildings in Lower Manhattan, signing them as SAMO©. These messages often took the form of cryptic, pseudo-philosophical one-liners, for example: "SAMO© AS AN END TO THE 9 TO 5 'I WENT TO COLLEGE' 'NOT 2-NITE HONEY' BLUES...", "SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO 'GOD'", or "SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS AND GONZOIDS..." These messages combined humour, social critique and a streetwise intellectuality, making SAMO© a talked-about phenomenon in the city's underground art scene.

SAMO© was instrumental in introducing Basquiat to the world of street art, and it served as a launchpad for his career. The directness, public nature, and ephemeral quality of graffiti were elements that he would carry into his work as a painter.

In 1980, growing tensions between Basquiat and Diaz, combined with Basquiat's solo aspirations, led to the end of the project. Basquiat marked this occasion by painting the message "SAMO© IS DEAD" on buildings around the city. Despite the demise of SAMO©, Basquiat would go on to become one of the most significant artists of his generation, while the influence of his SAMO© years remained visible in his work.

T is for The Death Of Michael Stewart

Officially titled Defacement (The Death Of Michael Stewart), this is a powerful painting by Basquiat, responding to the death of the young black artist Michael Stewart at the hands of the New York City Transit Police in 1983. The work serves as Basquiat's personal and political response to the incident, and it is considered one of Basquiat's most overtly political works. Basquiat and Stewart were part of the same New York City downtown scene and knew each other. Basquiat was reportedly deeply affected by Stewart's death, expressing fears that he could have met a similar fate. It was originally painted onto Keith Haring's studio wall, days after the incident. In 1985, when Haring relocated, he carefully excised the artwork from the studio's drywall to preserve it. In 1989, a year after Basquiat's passing, Haring commissioned an elaborate frame for the work. It was hanging above Haring’s bed at the time of his own death in 1990. The painting was the focus of a 2019 exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York titled "Basquiat's 'Defacement': The Untold Story," which explored its history and impact.

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982U is for Untitled (1982)

Untitled (1982) is Basquiat’s most valuable work ever sold at auction. On May 18, 2017, the painting was offered at Sotheby's Contemporary Art Evening Auction, with bidding kicking off at US$57 million. After an intense bidding war that extended for over 10 minutes, the piece finally sold for a staggering US$110.5 million. This sale set a new record for a Basquiat work that remains to this day, and also set a record for American artists at auction at the time.

Image © Sotheby's / Versus Medici © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Image © Sotheby's / Versus Medici © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982V is for Versus Medici

Basquiat's Versus Medici is one of the artist's most iconic works, considered an exemplary representation of Basquiat's ability to blend historical reference, socio-political commentary and his unique style. The title refers to the powerful Medici family, who were influential patrons of the arts during the Italian Renaissance, playing a crucial role in the promotion of art and culture and elevating artists. In Versus Medici, Basquiat seems to position himself in opposition to this illustrious history, suggesting a challenge to the established canon.

By placing a black figure at the centre of the painting, Basquiat could be seen as asserting his place in the artistic tradition, countering the Eurocentric bias of art history. It's a powerful statement of defiance and self-affirmation. The painting exemplifies Basquiat's talent for layering meanings and references, and his desire to grapple with complex issues of race, identity and power in his work.

Image © Whitney Museum / Basquiat’s page within the catalogue for the 1983 Whitney Biennial

Image © Whitney Museum / Basquiat’s page within the catalogue for the 1983 Whitney BiennialW is for Whitney Biennial

Basquiat was one of the youngest artists ever invited to participate in the Whitney Biennial, a prestigious contemporary art exhibition held every two years by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. The Biennial aims to showcase the most innovative and significant art being produced in the United States.

Basquiat was included in the 1983 Whitney Biennial when he was just 22 years old, a testament to the rapid ascent and recognition of his career. He was not only one of the youngest, but also one of the few black artists to have been included at the time. The Whitney Biennial played a significant role in elevating Basquiat's profile and confirming his status as one of the most important young artists in America.

A collage of three T-shirts from three different drops that Uniqlo has done in partnership with Basquiat.

A collage of three T-shirts from three different drops that Uniqlo has done in partnership with Basquiat.X is for Basquiat x (Collaborators)

Basquiat’s estate has long partnered with the licensing and marketing agency Artestar to ensure that his signature imagery and provocative messaging would live on for decades. This has made Basquiat a beloved and habitual collaborator with brands at various price points, especially in recent years. Notable collaborations include Basquiat x Supreme, Basquiat x Doc Martens, Basquiat x Yves Saint Laurent and Basquiat x Uniqlo – there have been several iterations of the latter, spanning from 2003 to 2023.

Y is for Youth

Basquiat was incredibly young during the peak of his career – he was only 22 when he was selected to exhibit at the Whitney Biennial, and only 27 when he died from a heroin overdose. His youth was a factor in his public persona, as the image of a young, black artist who had emerged from the streets of New York to become a star of the art world was compelling and unusual given the largely white and middle-aged establishment that dominated the art scene at the time. However, Basquiat's youth also contributed to the struggles he faced. The sudden fame and wealth were a stark contrast to his earlier life and put enormous pressure on him.

Z is for Zeitgeist

A huge reason why Basquiat's art is so successful is due to the fact that it perfectly captured the zeitgeist of New York City in the 1980s, with its raw energy, edginess and tension. It was a time characterised by considerable economic disparity, the devastating impact of the AIDS crisis, heightened racial tensions and the rapid gentrification of neighbourhoods. Basquiat's art captured this complex mix of energy, creativity, and social tension, with his graffiti-derived style of his paintings and emphasis on spontaneous creation. The content of Basquiat's art also often directly addressed the societal and cultural issues of the time, confronting racism, inequality and power structures.

He was friends with many of the key cultural figures of the time, such as Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Madonna, and his work reflects this intersection of art, celebrity, and commerce that was a significant feature of the 1980s. Basquiat's own life story – his rapid rise from street artist to superstar, his struggles with fame and addiction and his untimely death – mirrors the excesses, disparities and tragic losses of the era. In many ways, Jean-Michel Basquiat's art doesn't just reflect the zeitgeist of 1980s New York City: it is an integral part of it.