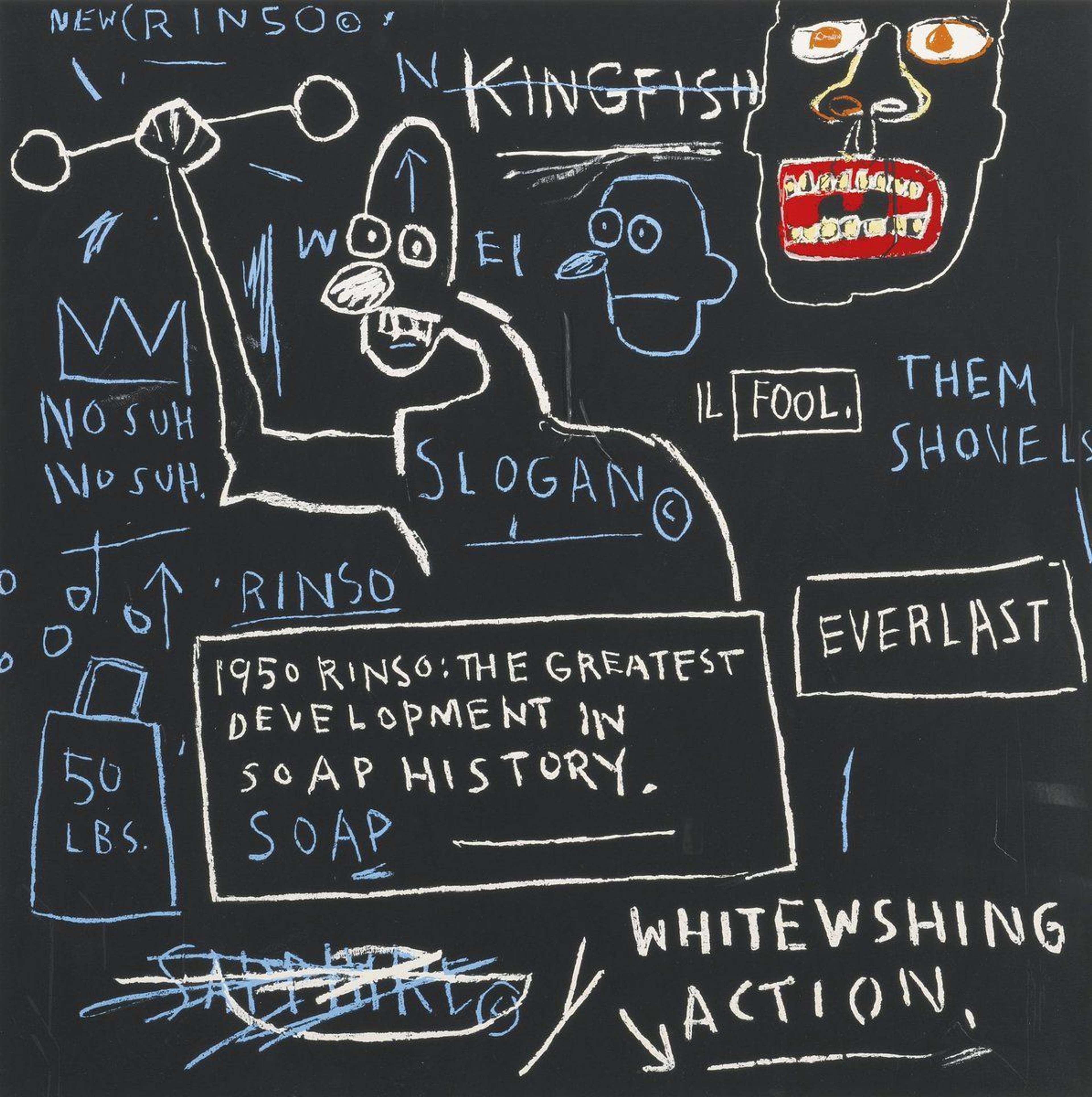

Rinso © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Rinso © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Interested in buying or selling

Jean-Michel Basquiat?

Jean-Michel Basquiat

59 works

From his days as a graffiti writer working on the streets of Manhattan in the late 1970s through to his totemic rise as a contemporary artist and tragic early death in 1988, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artwork offers a plethora of symbols and interpretations.

Here we take you through twelve of the most important Basquiat symbols and their meanings.

SAMO / SAMO©

A graffiti tag coined by Basquiat and his collaborator Al Diaz, SAMO — pronounced same-oh — started off as a private joke and went on to become an important symbol in Basquiat’s later work. It stands for ‘Same Old Shit’.

In May 1978, Basquiat and Diaz began to tag Manhattan buildings with the SAMO tag, adding a tongue-in-cheek copyright sign to the motif.

Later that year, the duo began to use spray paint to ‘get up’, attracting the attention of news outlets and even fellow graffiti and Pop artist, Keith Haring, with whom Basquiat forged a friendship.

In 1980, having given up graffiti, Basquiat incorporated the motif in his artworks.

The Crown

Synonymous with Basquiat’s œuvre, the crown has appeared in countless examples of the artist’s paintings, such as Red Kings (1981), Tuxedo (1983), King Alphonso (1982-3) and Back Of The Neck (1983).

Usually a central feature of any painting in which it features, there are many different theories as to the symbol’s meaning. Does it suggest Basquiat self-styled himself as a ‘king’ of art? Is it an icon of his vaunting ambition to become world-famous? Or is it a ‘crown of thorns’ referencing personal struggle? Nobody knows for sure.

Some think that the crown’s three points — which form a ‘W’ — are a reference to Andy Warhol, who was Basquiat’s de facto patron between 1983 and the artist’s death in 1988.

The Griot (Bard or Minstrel)

Depicted in works such as Grillo (1984), Flexible (1984), and Gold Griot (1984), the griot is a traditional West African musician, historian, musician, and/or poet.

An important part of the oral tradition in this area of the world, the griot as a motif references Basquiat’s keen interest in Black history and culture, as well as his own Haitian heritage.

Placing African cultural heritage at the centre of his distinctly modern practice, Basquiat’s references to griots could also be explained as a reflection on his own capacity as a dynamic storyteller using the medium of painting to target his audience.

Ishtar

Created in 1983, Ishtar is a large-scale triptych rich with the kind of hieroglyphic symbolism for which Basquiat was well known.

Aside from being one of the most highly regarded Basquiat works, the piece references Ishtar — the Egyptian Goddess of war and mythology — whose name is written repeatedly on the work’s central and right panels.

Speaking to Basquiat’s interest in Egyptian Mythology, Ishtar also features in the triptych Untitled (History of the Black People), aka The Nile (1983) – a work that deals explicitly with slavery in colonial, American, and Egyptian contexts.

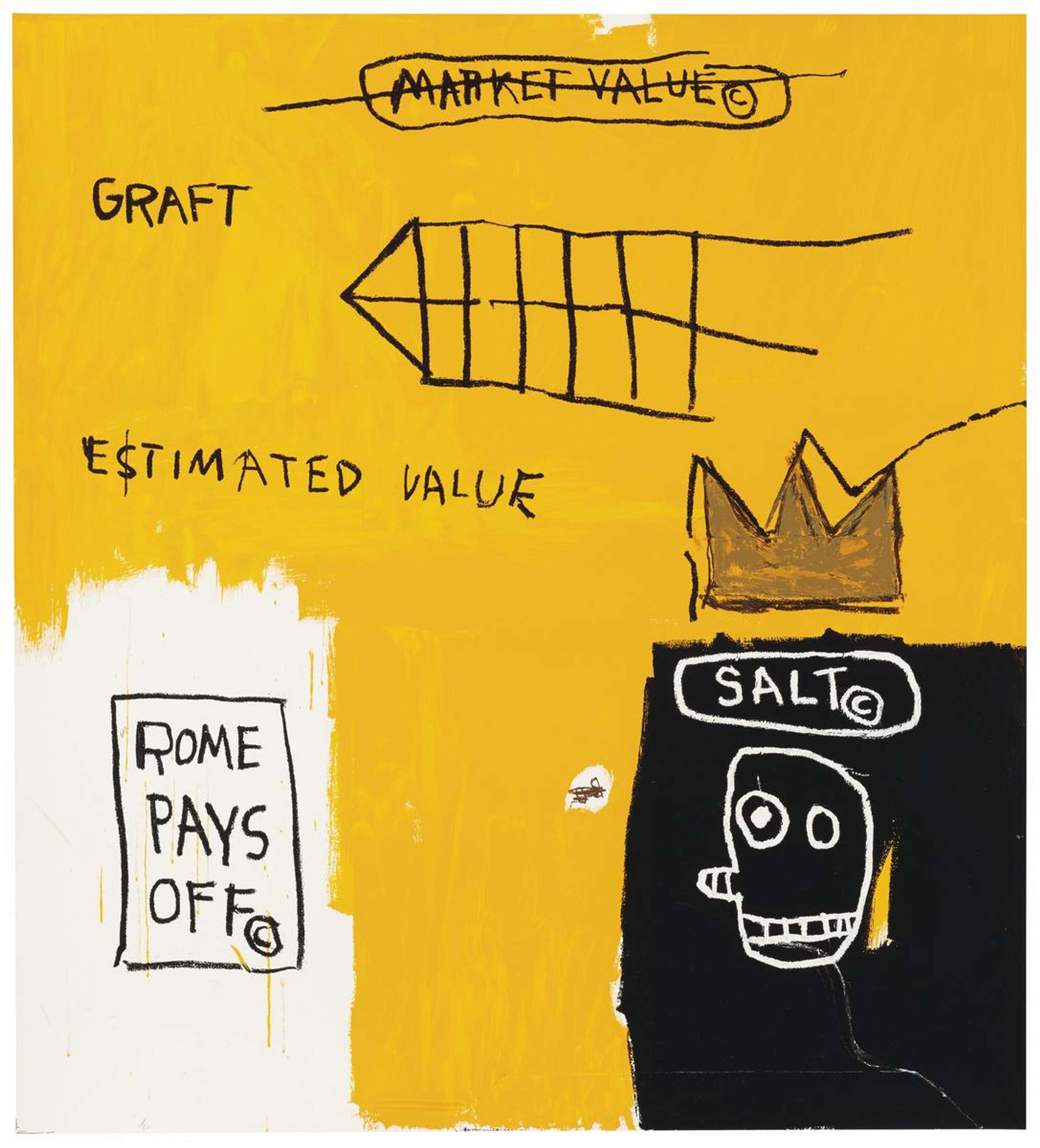

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982The Warrior

The ‘Warrior’ is another key symbol in the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Appearing most famously in the acclaimed self-portrait Warrior (1982) —a work the artist described as one of his ‘best paintings ever’ — it indexes Basquiat’s self-styled emergence as a messianic artist able to combine African, European, and American art histories.

In the warrior motif, many have read references to the Benin bronzes, Congolese statues, voodoo dolls, as well as Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning.

The Hammer and Sickle

An icon first adopted during the Russian Revolution as a symbol of workers’ and peasants’ solidarity, the hammer and sickle has since become synonymous with communist movements the world over.

It appeared in Basquiat’s work during 1982, with the diptych Hammer and Sickle (1982), and sketches Untitled (Sword And Sickle) (1982) and Untitled (Hammer And Sickle) (1982).

Central to the graphic iconography of the Cold War, Basquiat’s use of this political symbol references geopolitical events and the work of Andy Warhol, who in 1977 created his Hammer And Sickle series.

The Dinosaur

A motif reminiscent of childhood toys, the dinosaur appeared in Basquiat’s Snakeman (1983) as well as the world-famous Pez Dispenser — a simple, graphic work produced in 1984.

Depicting a dinosaur crowned by Basquiat’s three-pronged coronet, Pez Dispenser’s meaning is unclear.

With the work’s title referencing a collectible object of American consumer culture — the Pez sweet dispenser — some have theorised that the dinosaur is part of Basquiat’s desire to produce ‘suggestive dichotomies’. In this case, it could be argued that it serves to warn viewers of the nefarious nature of capitalism.

The Cosmogram

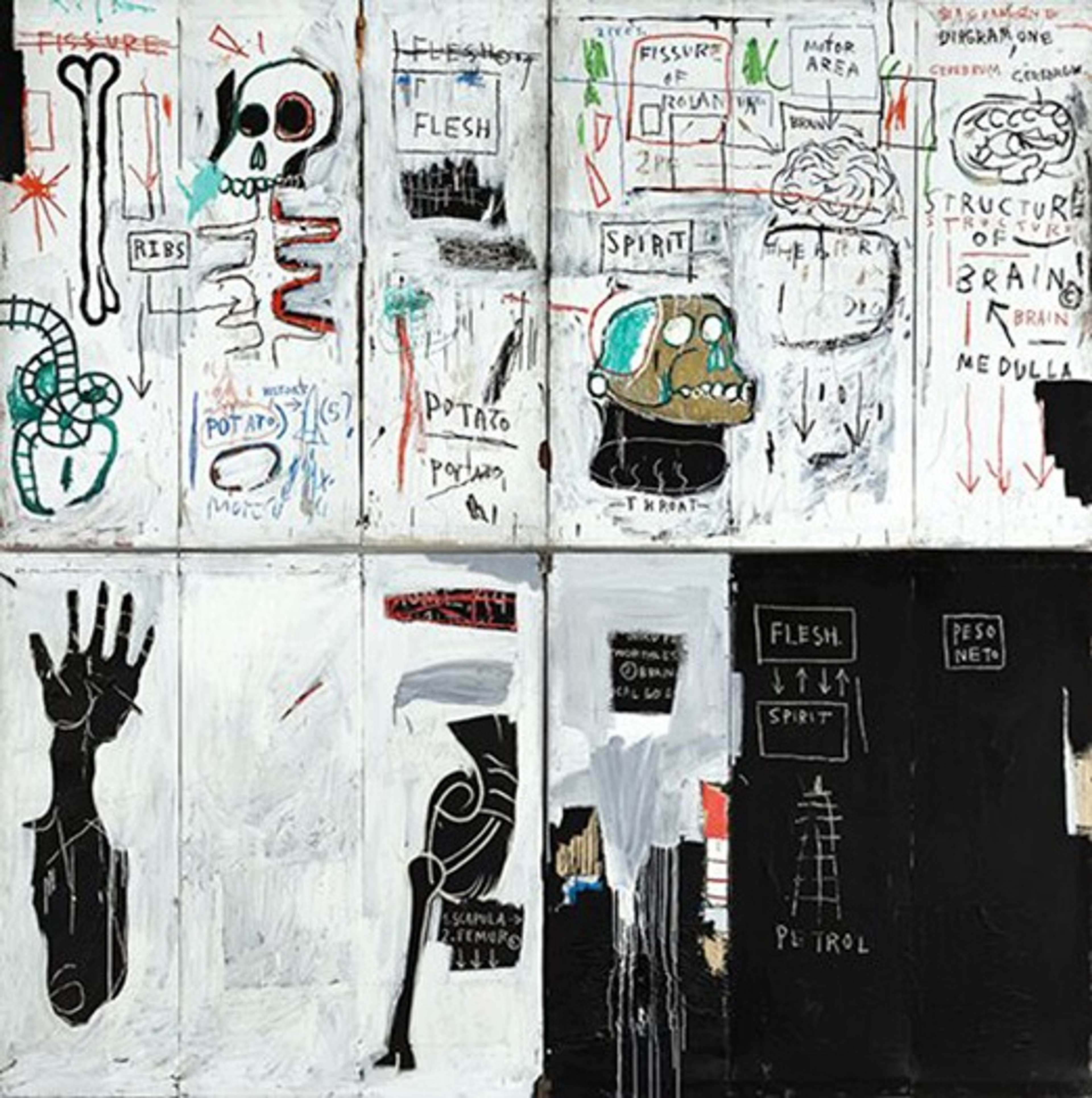

In Flesh And Spirit (1982-3) — a monumental, altarpiece-like work that takes its name from Robert Farris Thompson’s ground-breaking study of African religious tradition, Flash of the Spirit (1983) — Basquiat references the cosmogram.

What is the cosmogram? An important religious symbol for the Kôngo people of Africa’s Atlantic Coast, it represents many different things, including the cycle of life and one’s own position within the cosmos, as well as the origin, destiny, and projected future of mankind as a whole.

Flesh and Spirit © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982-3

Flesh and Spirit © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982-3The Serpent

The serpent — a cultural and religious icon found across the world — is a recurring feature of Basquiat’s effervescent paintings.

It features in St. Joe Louis Surrounded By Snakes (1982) and the 1983 work, Onion Gum. In the latter painting, a figure stands atop an angry-looking human head holding two snakes in his hands.

But what does it mean? Well, it’s possible the snakes may be a reference to Japanese art, in which they often feature. At the top right of the image, the phrase ‘MADE IN JAPAN’ is scrawled in capital letters.

Three Vertical Lines

This oblique symbol features in Basquiat’s lettering; he would write of the ‘E’ characters with just three horizontal lines.

A symbol used by ‘Hobos’ — itinerant Americans who, in their millions, left their places of origin in search of food and lodging during the Depression era — it speaks to a love of coded communication.

According to Henry Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide To International Graphic Symbols (1984), three vertical lines mean: ‘this is not a safe place’.

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982

Untitled © Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982Masks and Skulls

In what has been interpreted as a reference to his father’s Haitian origins, masks and skulls are prominent in Basquiat’s œuvre, featuring in early works such as Untitled (1981) — painted when the artist was only 20.

They signal voodoo rituals and memento mori — two prominent features of Caribbean-African and European culture and art history.

In 2020, one of Basquiat’s head-based paintings — also entitled Untitled (1982) — broke an auction record when it went under the hammer at Sotheby’s, becoming the most expensive Basquiat work on paper.

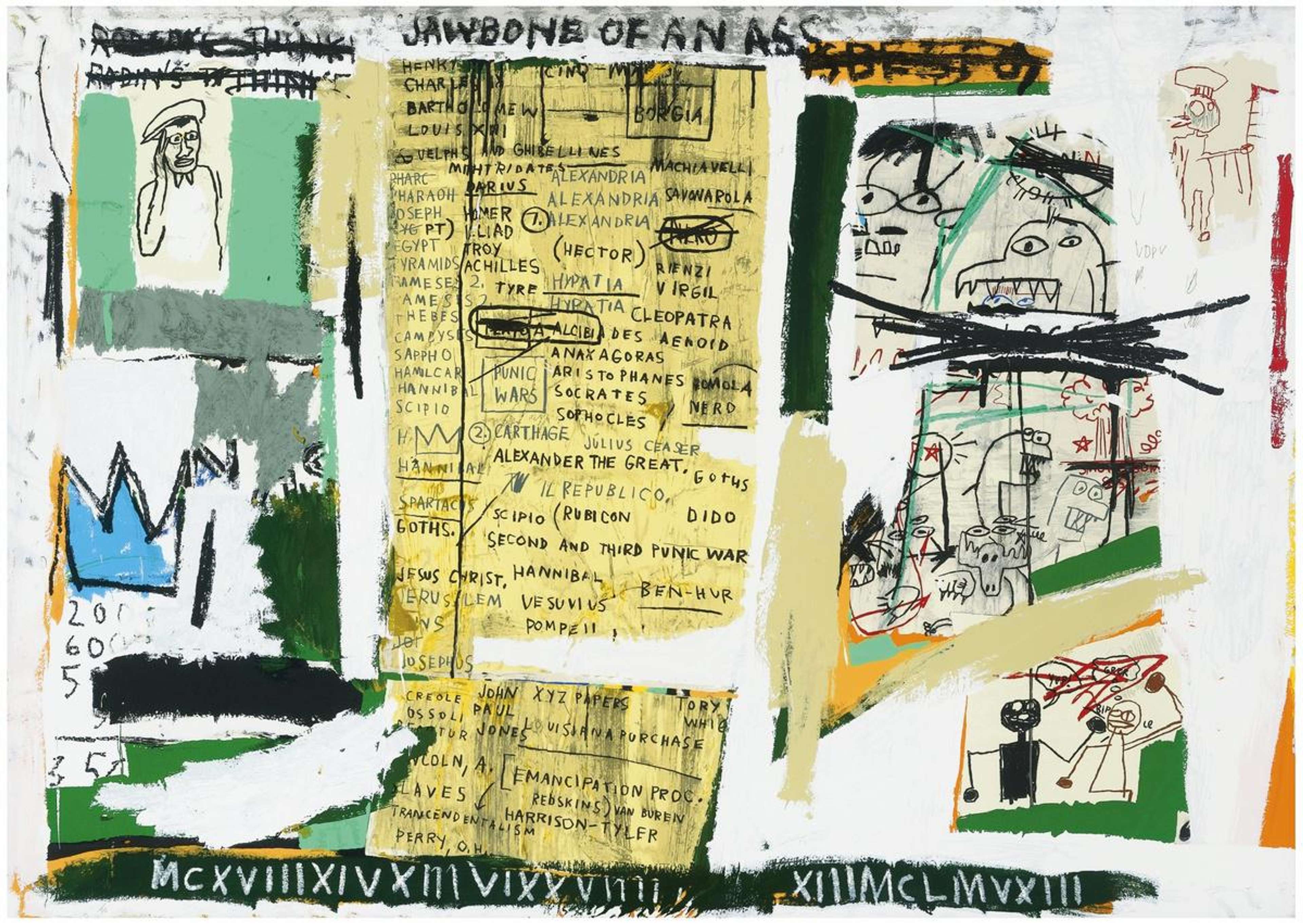

Text

Last but not least, text is a central feature of Basquiat’s artworks.

It features in many of the late artist’s works, from his Anatomy Studies series all the way through to his well-known piece, Hollywood Africans In Front Of The Chinese Theatre With Footprints Of Movie Stars (1983).

Eschewing its typically descriptive function, in Basquiat’s art text assumes poetic, symbolic, and indexical qualities.

Cryptic to say the least, text is often employed as an almost baroque device designed to accord artworks greater detail and decoration, and to play with meaning.