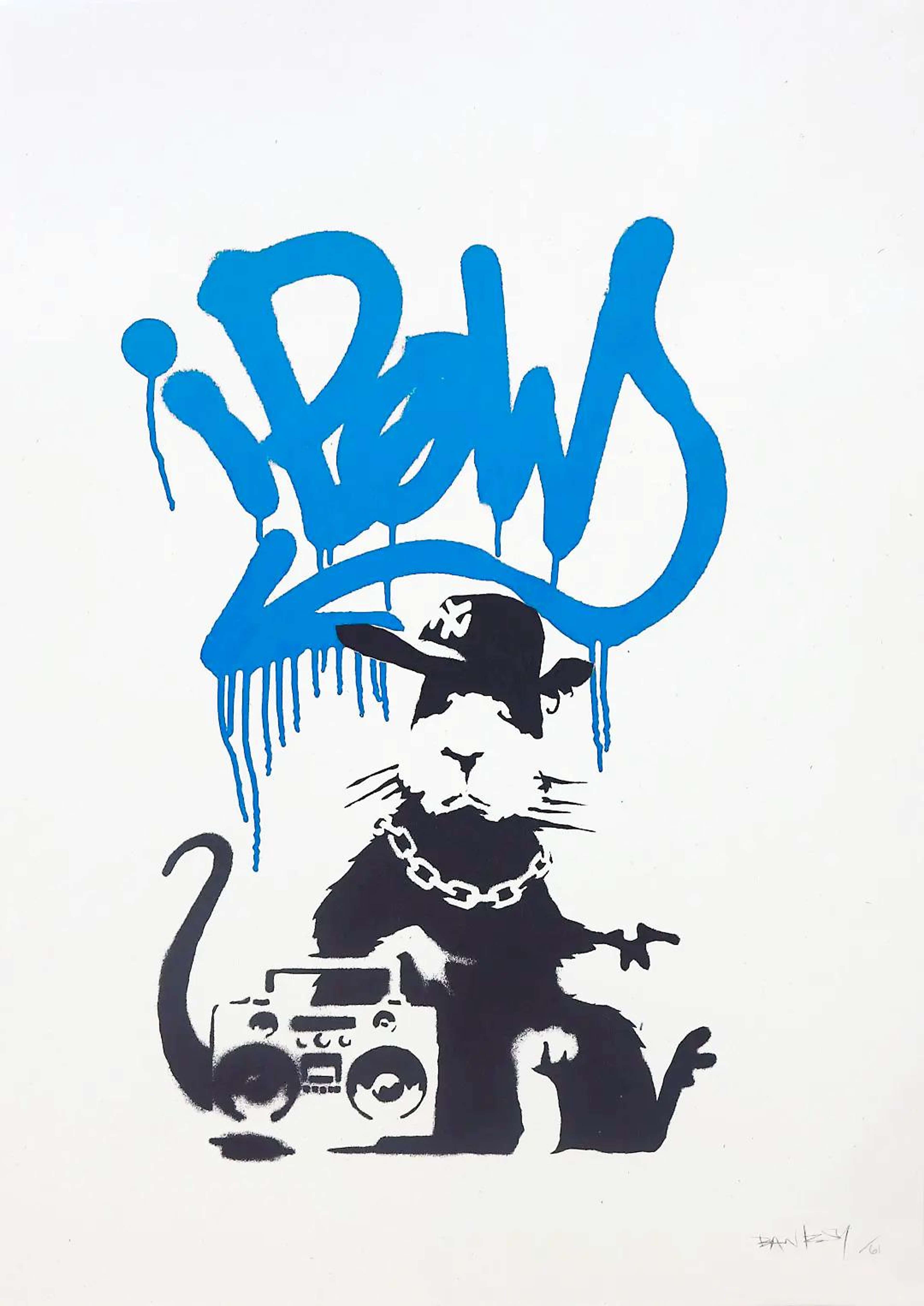

Gangsta Rat (AP Green) © Banksy 2004

Gangsta Rat (AP Green) © Banksy 2004Live TradingFloor

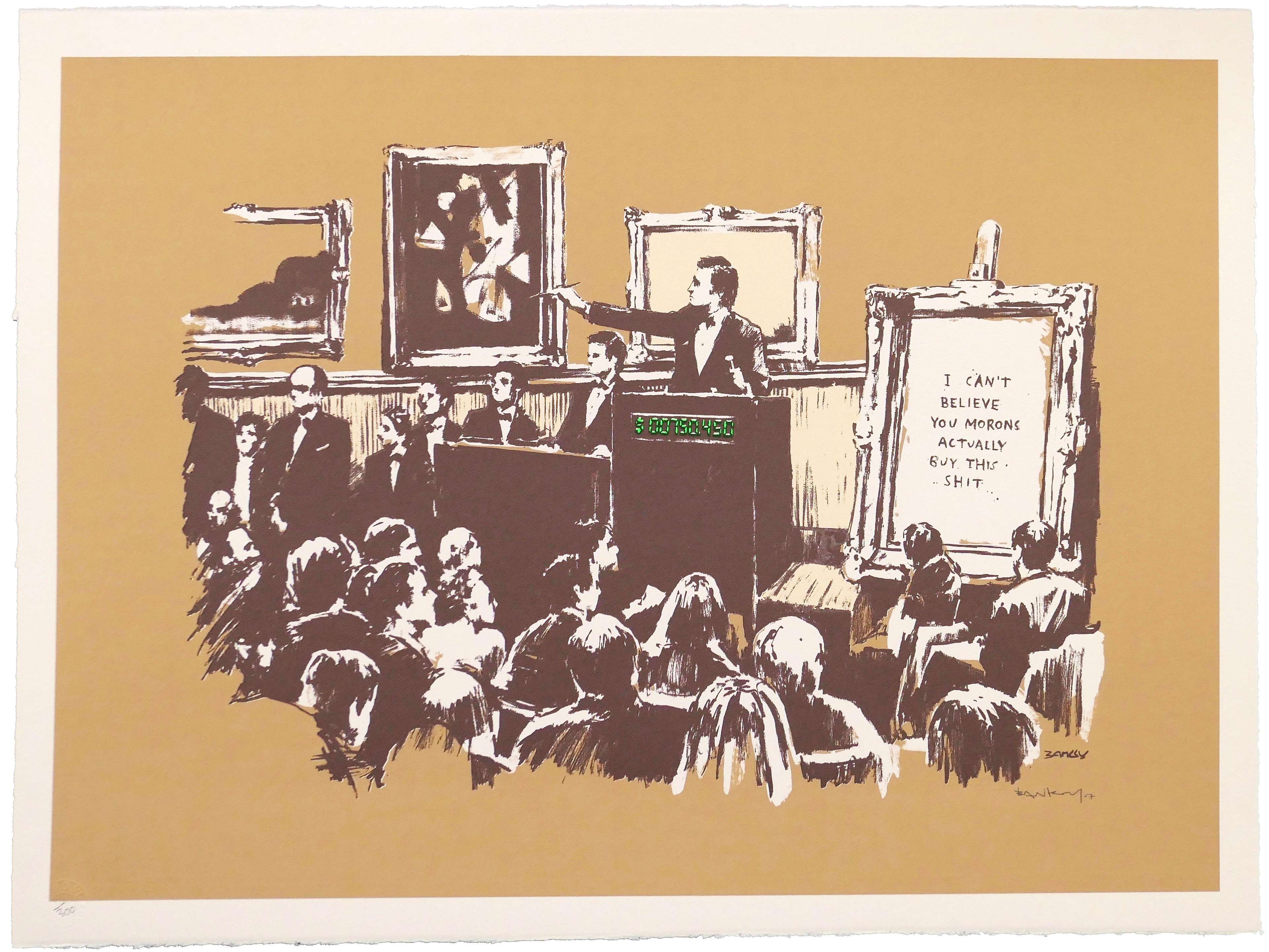

While prints are a great option accessibility-wise for those looking for reliable alternative investments, or who are hoping to acquire art without the extreme price tags of originals, we understand that the world of art prints can be off-putting and jargon-heavy. Given that our mission is to forego the elitism and exclusivity usually associated with the commercial art world, this handy guide aims to demystify print production and clarify what print types mean in real terms, when it comes to value.

Read on to find out the answers to sensible questions such as “Are Artist Proofs worth more?”, “What does Hors-Commerce mean?”, and “What is a trial proof print in art terms?”.

Print Glossary

Artist’s Proof (AP)

A print annotated ‘Artist proof’ or ‘AP’ corresponds to a certain number of prints reserved for the artist, aside from the edition that was produced for sale. Traditionally, they were a form of quality assurance, and sometimes payment, for the artist—coming from the beginning of the print run, they tended to be better quality, crispy clean prints. They were often saved by the artist for friends and family, or to be sold at a higher value than the main edition. For this last reason, artist’s proofs have traditionally been limited to around 10% of the total number of prints (edition + proofs). Often, artists will also mark the number of these prints in a different manner, such as roman numerals, or alphabetically, to differentiate them from the main edition and clarify how many were made.

Now that printmaking has evolved, artist’s proofs take on a simply formal role, but are also a means for the artist to create a more exclusive, more valuable version for sale. Because print technology has evolved, and print-runs are largely consistent in quality, for some artists, the only difference between their main edition and their run of artist proofs will be in the little ‘AP’ annotation - and the price. Artist proofs are still generally more valuable, because of their exclusivity.

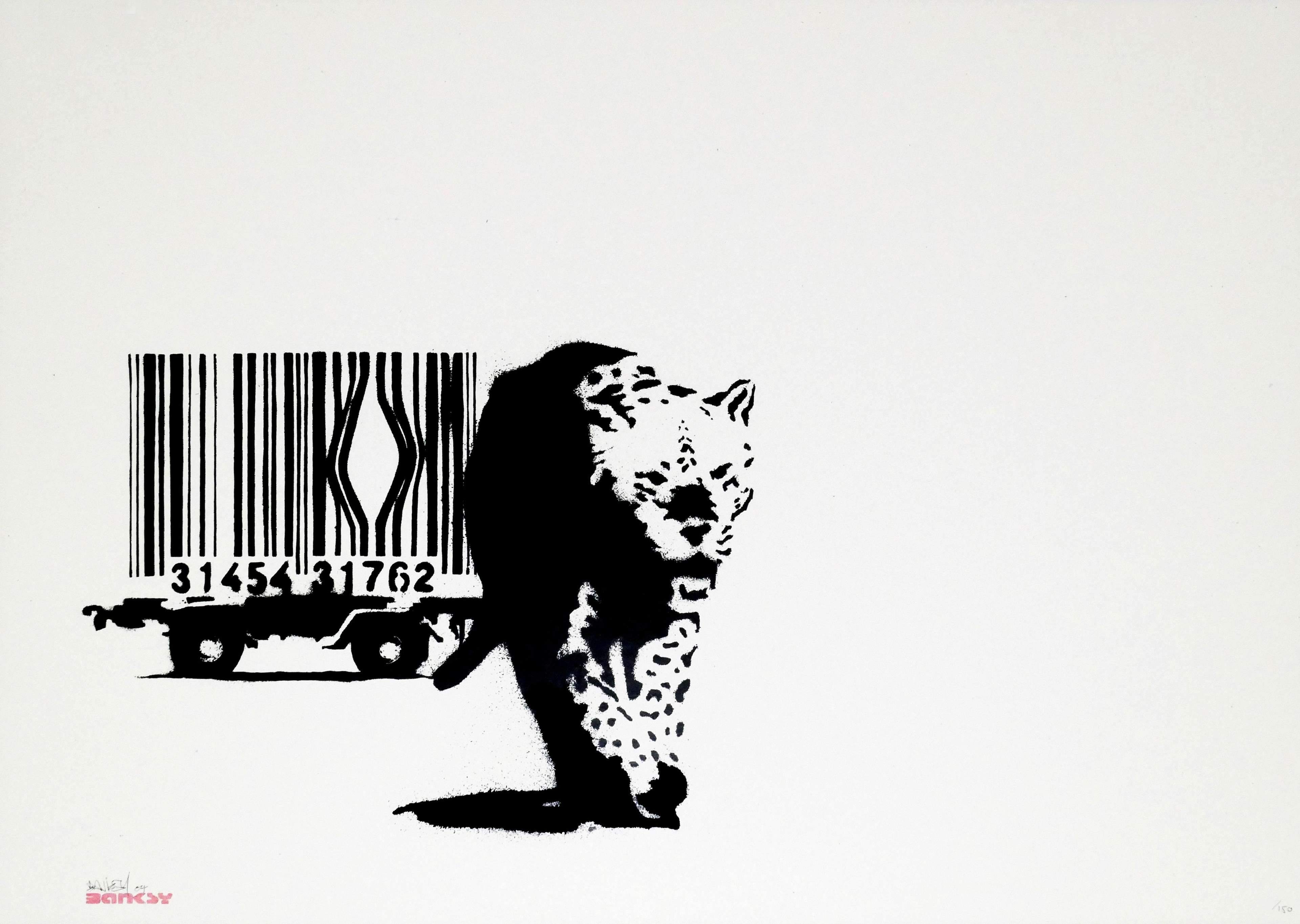

Many artists will have added further desirability to their APs by making them in unique colourways. Banksy, for example, has capitalised on his artist’s proofs in order to offer more colour variations of his prints. He produces quite an extreme and certainly unconventional number of artist proofs, well over the conventional 10% of the total edition. His Gangsta Rat, has corresponding artist’s proofs in as many as 6 colourways and a total number of 257 artist proofs (compared to a total main edition, of 500). But what does this large number of Banksy artist proofs mean to their value?

Part of Banksy’s practice as an artist will always be trialling artworks in a street art setting—most of his prints were created this way. Because of this, and because of the many colourways Banksy’s APs present, despite their annotation by the artist, these prints are closer in function to other artists’ Trial Proofs (see later).

Artists may also add to the exclusivity and value of their artist’s proofs by taking the effort to add hand-detailing to them, such as adding watercolour. The addition of detail by hand doesn’t immediately mean the print is an AP, however, if it is not labelled as one.

Bon À Tirer (BAT)

From French to English, this translates as ‘good to print’. Bon À Tirer prints are labelled as such from among the many test prints a printmaker will make, in the process of perfecting the print for the artist. A ‘BAT’ annotation signals that the conditions for, State, and quality of the print are now right, and that the printmaker and artist have agreed that the commercial edition can now be printed. A printer will also refer to the BAT print to quality check the prints as the edition is being produced. As such, they are often considered to be ‘the’ best print of the given artwork, they are rare, only one per edition; and very valuable.

Catalogue Raisonné

This is a book, written by the artist’s main printer, agent or an expert on their work, which indexes the artist’s full works. They are usually produced once the artist has reached such a level of fame that there is a concern about forgeries, and often (for the unlucky ones) after their death. For some prolific artists— we’re looking at you, Andy Warhol—there will need to be many volumes published to contain their full career, and revised editions for when new authentic works come to light and old ones are proved fraudulent.

You can read more about the ongoing creation of a comprehensive Warhol catalogue raisonné here.

The catalogue raisonné is a vital source for prospective and experienced collectors alike: a print is only likely to sell for its true worth if its provenance can be produced, which, among other sources, always involves cross referencing the work with the catalogue raisonné. There are exceptions to this rule, and artists by nature are not known for making themselves available for such boring, taxonomic bureaucracy, but the catalogue is always the first port of call for determining the number of proofs, edition size and a wealth of other details about the print’s production.

Cover of "Keith Haring, Editions on Paper 1982-1990", Werner Jehle and Hatje Cantz © 1997

Cover of "Keith Haring, Editions on Paper 1982-1990", Werner Jehle and Hatje Cantz © 1997Dedicated Prints

An artist might have inscribed a personalised message to a friend, lover, or patron on a print, particularly if they initially gave that print as a gift. Despite common misconception, because this sentimental treatment is highly personal, it will decrease the value of the print in economic terms.

Similarly, but not actually a form of dedication, the addition of signatures by collaborators or other celebrities to an artwork, especially alongside the artist’s, will increase the print’s value. Warhol’s 1975 Mick Jagger print portfolio, comprising five prints of the rockstar, is an example of a double signature that has made the prints exponentially more desirable, among the most valuable Warhol prints on the market.

Double Number Prints (DN)

Proof that even professional artists are human, double number, or duplicate, prints sometimes occur where there has been an error in numbering the edition. Given that poor record keeping is usually (though not always) the hallmark of an artist at the beginning of their career these mistakes are often not noticed until many years later, when the authenticity and correct editioning of their work comes under greater scrutiny. In this case, a print discovered with a number already attributed to another print will be annotated DN and, unfortunately for the owner of the second print, decrease in value.

In rarer cases, the double number error will be discovered by the artist or printer while the edition is still being produced. Rather than compromise a print by erasing the original number (which could lead people to question its authenticity down the line and looks messy) the artist and printmaker might annotate the mistake and miss out a later number of the edition to make up the correct total.

Evidence that this mistake is particularly common among artists pre-fame, Banksy is a key offender when it comes to double numbers. Many of the prints from his early career, when he was even selling from car boots, were inaccurately numbered—unbelievably today, they could take up to a year to sell out, and so were produced over a longer period—leading to a great number of double number prints.

Edition Size

An edition is a quantity of prints of the same artwork, made from the same plate (or plates if the design has layered colours) and released on mass for the same price. For limited edition prints, a printmaker will produce a given number of prints, agreed with the artist beforehand. Occasionally, the edition number change during production, but the catalogue raisonné can often provide clarity where this is the case. Limited edition prints are usually (though not always) numbered from the edition size, for example ‘7/100’. Smaller edition sizes, as they make a print rarer, tend to correspond to higher prices, though this of course depends on the popularity of the particular artwork.

Open editions refer to a print that has not been limited in edition size. They are inherently less valuable because its rarity has not been controlled by the artist.

Editions may be signed or unsigned, but with exceptions, the artist will either sign the full edition—i.e. all the copies—or not. Often, they will produce one edition of signed prints, and a larger edition of unsigned prints, with a lower value.

Épreuve d'Artiste (EA)

This is just the French for an artist proof, you’ll see it frequently on the works of artists with French printers like Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Similarly, ‘Épreuve de Collaborateur’ refers to either copies reserved for a secondary artist, or to the printer’s proofs.

Final Proof

The English equivalent of ‘B.A.T’, this is less often used to annotate a print, as the French seems to satisfy everyone, but it is used in ‘art speak’ to refer to the same print. Speaking of other, less common terms for the BAT print: they may also be labelled ‘Ready to Print’ (RTP), or the ‘Master Print’.

Hors-commerce (HC)

Given to galleries as display copies and marking the prints not for primary sale, often these prints are collated in their portfolios, and were used to advertise either the full portfolio or individual artworks. Given that they were often distributed as full sets—portfolios—of artists’ series, where they are still in the full set for purchase or sale, they can fetch a higher value for this attribute. Given that galleries usually have the expertise and motivation to preserve their copies carefully, these prints can be in the best condition on the market.

Outside of Edition

If a print is referred to as ‘outside of the edition’ or ‘out of edition’, this means it is either unnumbered, where the only edition produced was numbered, or it otherwise does not match the recorded specifications for the print, in the catalogue raisonné. Not to panic though, this does not automatically mean the print is not genuine; there are several reasons for a print to be outside of edition, such as imperfect record keeping on the part of the artist or printmaker, or that the print is an unlabelled trial proof. Auction houses will commonly denote this last circumstance by describing a print as a ‘proof aside’ (from the edition) but the print is not annotated as a certain kind of proof, and the auction house does not specify one. It is worth looking into, as sometimes out of edition prints will be recorded in the catalogue raisonné as known exceptions, and sometimes they will not. Out of edition proofs are generally lower in value, and in the last case—that they cannot be cross-referenced to the catalogue raisonné- they will be priced the lowest and may even be difficult to authenticate without other very solid sources of provenance. For Warhol prints, it is well-recorded that because his studio, the ’Factory’, was so full of people there were many prints stolen or retrieved from the wastepaper with or without permission by visitors and disgruntled employees alike. For out of edition prints where this is the case, the provenance will be very murky and they will be worth less as a result.

Plate

The plate is the basis for all fine art prints, excepting digital prints. It is what duplicates an image many times, without much variation in the print produced.

Usually, once the agreed upon edition size has been created, the printer will be contractually obliged to destroy the plate or return it to the artist, so that they cannot profit from further, unlicensed editions. In exceptional circumstance, where an artist and printer have quarrelled, or a printer has gone defunct, this destruction does not occur, which can be the reason for lots of out of edition prints. These are usually less valuable given they are unlicensed, though this can be seen as a positive source of greater accessibility to in demand artists or prints. Very occasionally, the plate itself will be available for sale, and usually achieve impressive price.

There are certain quirks relating to medium that mean a plate will have a different relation to the final image. For example, screenprinting does not use a plate as such—it uses a silkscreen—but for the purposes of this definition, a silkscreen is essentially synonymous with a plate. It too it is the consistent starting point that produces a consistent edition, through direct application. Depending on the material out of which the plate is made—wood, lino, metal, or faced-metal, plates will have different longevities. Read more about different print mediums here.

Printer’s Proof (PP)

Printer’s proofs are similar to artist’s proofs, only they are reserved for the printmaker, as reference copies, and as part of the payment contract. Often, they too are numbered in roman numerals or alphabetically, to differentiate them from a main edition numbered in Arabic numerals (or vice versa). Printer’s proofs might be retained for reference during the printing process, or for the printer’s personal portfolio of work, or distributed between staff or other acquaintances. There are traditionally fewer printer’s proofs than artist proofs, leading them to be even more valuable.

States

If a print has different states, this means the image exists in different versions, because changes have been made to the plate (or plates) between printing.

Sometimes the new state will entail the addition of new plates because different colours require different plates to be layered. For Keith Haring, the usual difference between states was an addition of colour. His iconic artwork, Growing 1, was released in two main editions: Growing 1 (First State), a black and white edition of 10, and a subsequent full-colour edition of 100, Growing 1.

Warhol also produces different colour states, but unlike Haring they are not always separated into separate editions. Instead, he might release the varied prints as Unique Trial Proofs or as a Unique Editioned Print (see later).

Later states may also adjust the composition of an artwork either by changing the actual marks—the linework and shading of the print— or by expand the field and scale of the work, especially if an artist was not satisfied initially. If the artist is reworking the actual mark-making of the print, because the nature of most printmaking mediums is a one-way street, earlier states will have fewer details, and later states will be more heavily worked into. Picasso and Chagall often produced new states in this way because they are unhappy with the initial print result.

There is no definitive answer as to which states are worth more, it depends on the way an artist has used the possibility of different states, often it’s a matter of preference as to which version you think’s best. Given that any print with a different state to the main edition is more likely to be differentiated from the main edition by being labelled as an AP/TP/PP, and produced in a more limited quantity, overall, having a print from an unusual state means a higher value. Earlier states, and particularly ‘first state’ prints may be rarer, if they were produced as a part of the creative process. Conversely, ‘final state’ prints may also hold greater value, as an artist may return to a work after the initial edition with intentions of tinkering with and reworking it; often, these revisions don’t make it to a main edition, as the public is not as obsessive as the artist, or demand simply wasn’t there at the time.

Trial Proof (TP)

Trial proofs are prints created along the journey of producing an edition, and they pretty much do what they say on the tin— trial the printing plate and image. Sometimes the trial proof might have more specific intentions, such as to test available colours of ink, in which case they are annotated ‘Colour Proof’ (CP) or ‘Colour Trial Proof’ (CTP) instead. Dependent, as ever, on other factors, colour proofs are often a very desirable choice for collectors, as the very visible uniqueness of one adds a special air of prestige. This is the case with Warhol’s prints labelled ‘TP’. Known for his studio’s proliferation of prints, and for being a master printer himself who was heavily involved in the production of his prints, Warhol liked to experiment in the course of creating his prints, producing many colour variations and registrations— the resulting abundance of trial proofs have proved very popular and can attain good sums of money. His print The Marx Brothers is a brilliant example of how much Warhol tweaked his designs as he printed them— the resulting trial proofs make for quite an easy spot the difference…

Left: The Marx Brothers (F. & S. II.232) © Andy Warhol 1980 | Right: The Marx Brothers (TP) Andy Warhol © 1980

Left: The Marx Brothers (F. & S. II.232) © Andy Warhol 1980 | Right: The Marx Brothers (TP) Andy Warhol © 1980For some artworks, Warhol never formally created trial proofs, and for these— Flowers, Electric Chairs, Space Fruit: Oranges, Kiku, Love, Martha Graham—there are corresponding Out of Edition prints that take the place of the TPs. These make Warhol a key example of the circumstances in which a print outside of edition may be worth more than one that is from the main edition... but always take extra care in authenticating such prints.

Working Proofs

Confusingly, artists may also have produced working proofs. Like trial proofs, these play a role in the decision making for the print-run but are a less formal category, so will rarely be titled or numbered in any coherent way. This informality is also because these are prints that were likely never intended to make it onto the market—if they do, it is usually after an artist’s death. Working proofs are often highly involved artistically, not the sort of polished product an artist aims to make public: they might have casual annotations and scribblings by either printer or artist, or both, to signal edits to make. These annotations are not for everyone, given that they might serve as a distraction from the original image, but sometimes they will add value to a print because they give an insight into the artist’s practice, serving as an art historical detail. There are examples of Harland Miller’s working proofs on the market, complete with annotations by the artist himself.

Unique Edition Prints

This refers to prints that are released and marked up as a single edition—they are signed, numbered, and released as an edition—but that, unlike a standard edition, are unique from one another in some way. It is a great way for artists to provide their buyers with an even more special experience of ownership; in owning any print, let alone a unique editioned print, you own an invaluable and irreplaceably authentic bit of art history.

Sometimes, it is a portfolio that has been released as a unique print edition. Warhol’s Gems portfolio, for example, was released in an edition of 20 portfolios (+ 5APs), each containing the four different gems, but the colourways of these individual prints, and the combination of the colourways, varied by portfolio. It is an inventive way of maintaining his experimental practice in the face of the standardized conventions of editioned prints and commercial sale.

As stated above, many artists will create a unique edition that varies by the plate state.

How does the edition affect the value of a print?

Ultimately, the value of a print is dependent on many factors; where the print sits in (or outside) the edition is just one of these. But artists are creatures of habit, and will largely be consistent about the considerations, such as scarcity, that add to a particular edition or artwork proof’s value. Because of this, it is possible to make generalisations about the value of, say, Warhol’s trial proofs compared to his main edition, or to those of another artist.

If you would like to speak to experts on artists with blue-chip print legacies to discover more about the quirks of individual print oeuvres and what this means for the value of their prints, we are more than happy to help. We can offer tailored advice about individual prints or a free valuation.