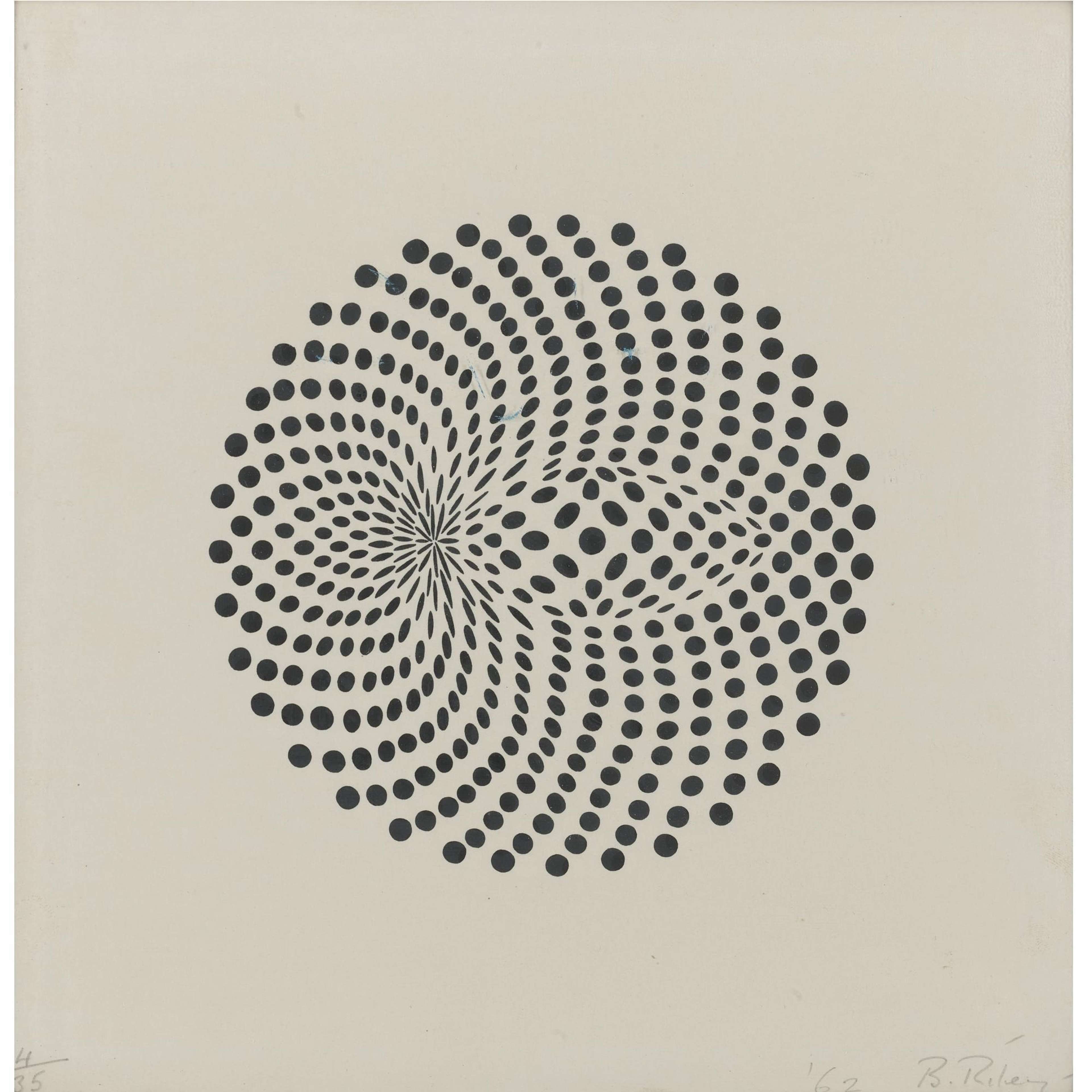

Nineteen Greys D © Bridget Riley 1968

Nineteen Greys D © Bridget Riley 1968

Bridget Riley

112 works

Pointillism, a painting technique synonymous with the divisionism method, is characterised by the use of small, distinct dots of colour applied in patterns to form an image. Developed in the late 19th century by French painter Georges Seurat and his contemporary Paul Signac, Pointillism emerged as a branch of Impressionism, yet it was distinct in its methodological approach to hue and light. Its ability to abstract through form and ability to trick the eye was highly influential, especially visible in the art of British artist and Op Art proponent Bridget Riley.

Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp © Georges Seurat 1885

Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp © Georges Seurat 1885Pointillism and its Historical Context

Like much of Riley’s work, the historical roots of Pointillism are anchored in the scientific research of colour and optical effects. Scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood played a crucial role in understanding how colours mix in the eye rather than on the palette, leading to the theory of optical mixture. This theory posits that colours juxtaposed in small dots would blend in the viewer's eye to produce a more vibrant luminosity than could be achieved by traditional methods of mixing pigments. Seurat, deeply influenced by these scientific theories, sought to apply them to his art in a methodical way. His masterpiece A Sunday Afternoon On The Island Of La Grande Jatte is a quintessential example of the movement that would become Pointillism. In this work, Seurat applied tiny dots of pure colour side by side which, from a distance, blend in the viewer's eye to create dynamic hues that appear to be in movement. This technique was revolutionary, as it moved away from the strokes and blends of Impressionism towards a more scientifically grounded and abstract approach.

Pointillism represented a philosophical approach to representation in art, as the technique prompted artists to think about the perception of colours and the science behind it, influencing not just the Neo-Impressionists but also later generations of artists. Despite its initial mixed reception – with critics often perplexed by its meticulous and time-consuming process – Pointillism laid foundational concepts for the development of various modern art movements. It can be seen as a precursor to the colour theories that underpin much of modern and contemporary art, including Abstract Expressionism. In the case of Riley, Pointillism's emphasis on the optical and perceptual effects of juxtaposed colours can be seen as an early influencer of her approach to Op Art. Riley's work, focused on creating vibrant optical sensations through precise, geometric patterns, echoes the Pointillist technique of manipulating viewer perception through colour and form.

Bridget Riley's Artistic Journey

Riley was born in 1931 in London, and is a prominent British artist renowned for her contributions to the Op Art movement. Her artistic journey is marked by a rigorous exploration of visual perception, focusing on the dynamic interactions between colour, form, and light. Riley's work invites viewers into a world of optical illusions, where static surfaces seem to move, and colours vibrate with energy.

Her early career began with a traditional art education at Goldsmiths College and later at the Royal College of Art, where she was exposed to a variety of artistic influences, although she left both without qualifications. Initially, her work was figurative; however, she soon embarked on a transformative path towards abstraction. The turning point in Riley's career came in the early 1960s when she began to develop her signature style—creating black and white geometric patterns that produce sensations of movement and colour.

Riley's exploration into optical art was partly inspired by the work of Victor Vasarely and Pointillism’s focus on colour theory and perception. Her breakthrough piece, Movement In Squares, is a testament to her ability to create a sense of depth and motion on a flat surface. Following this, her work Fall garnered international attention, firmly establishing her as a leading figure in the emerging Op Art movement. By the late 1960s, Riley reintroduced colour into her work, further complicating the visual effects of her pieces. She meticulously studied the interactions between hues and how they could be arranged to evoke a sense of rhythm and space. This period marked a significant evolution in her artistic approach, as she began to experiment with the emotional and spatial possibilities of juxtapositions.

Throughout the decades, Riley has continued to refine her exploration of perception, experimenting with new shapes, colours, and compositions. Her work has evolved to include curves, diagonals, and more complex relationships, always maintaining a focus on the interaction between eye and canvas. Riley's contributions to art have been recognised with numerous awards and exhibitions worldwide. Her influence extends beyond the art world, impacting design, fashion, and popular culture, illustrating the broad appeal and relevance of her optical explorations.

Riley's Adaptation of Pointillist Techniques

Riley's adaptation of Pointillist techniques marks a pivotal moment in her early artistic development, illustrating a profound engagement with the principles of colour theory and optical perception that would define her career. In 1959, amidst an art world dominated by the expressive, gestural works of male painters, Riley's approach was notably different. At the age of 28, she embarked on a path that diverged significantly from the prevailing trends of the time, characterised by a meticulous and analytical exploration of visual effects. Riley's fascination with Pointillism began in earnest with her encounter with Georges Seurat's Bridge At Courbevoie, one of the gems of The Courtauld Gallery. Her decision to paint a copy of Seurat's work was an immersive study into the mechanics of colour and perception and, although the painting was available for viewing, she chose to use a reproduction within a book as her working model.

The original work is relatively small, measuring 46 x 55 cm, while the print Riley used for reference was even smaller at 18 x 22 cm. For her reinterpretation, Riley selected a much larger canvas, 76 x 96 cm, closely mirroring the proportions of her reference but slightly elongated compared to Seurat's original. Given the increased size of her canvas, one might have anticipated Riley to proportionally enlarge the dots from her model. However, she opted for a less numerous but significantly larger scale for her marks, maintaining a divisionist style but magnifying Seurat’s techniques for closer examination. Riley curated a palette centred around heightened primary tones: starting with light blues, then adding soft pinks, and finally, light yellows. She expanded the colour spectrum by incorporating vibrant red dots within the green foreground. This inclusion of red, despite its absence in her reference image, was a thoughtful exploration, acknowledging its presence in Seurat’s broader palette.

By enlarging the scale and intensifying the dots, Riley delved deeper into Seurat's technique, seeking to unlock the secrets of how juxtaposed dots of complementary shades could create vibrant, luminous effects that transcend the limitations of the individual hues. She expanded upon Seurat’s foundational principles, applying them to her own landscapes and eventually abstract compositions. Her rendition of the sun-filled hills of Tuscany, painted in a Pointillist style, demonstrates her ability to apply these techniques to different subjects, showcasing her versatility and deep understanding of colour interaction. This intense study period represented a significant breakthrough for Riley, as evidenced by the fact that her rendition of this work still hangs in her studio.

Legacy and Influence: Pointillism in Riley's Art

The insights gained from studying Seurat's method catalysed her transition towards pure abstraction and, over the following years, she produced her first major abstract paintings – characterised by repeated geometric patterns. These works were a departure from her earlier figurative paintings, signalling a new direction that focused on the optical and perceptual possibilities of abstract art. The exhibition Bridget Riley: Learning From Seurat at the Courtauld Gallery of Art in 2015 highlighted the significance of Pointillism in Riley's oeuvre. This exhibition underscored how the lessons learned from Seurat represented a philosophical alignment with the principles of optical mixing and the dynamic potential of colour in the viewer’s eye. She goes one step further, however; while Seurat's work aimed to enhance the realism and vibrancy of painted scenes through a scientific approach to colour, Riley's abstract compositions explore the mechanisms of perception itself, investigating how simple forms and shades can be arranged to produce complex visual experiences.

Riley's adaptation of Pointillist techniques was a crucial step in her journey towards becoming one of the foremost proponents of Op Art. By integrating the scientific and analytical aspects of the movement with her own innovative approach to abstract patterns, Riley carved out a unique niche in the art world. Her work offers a contemporary reinterpretation of the exploration of visual perception, which continues to influence and inspire.