Bridget Riley's Artistic Journey: From Cornwall to Egypt

Coloured Greys 2 © Bridget Riley 1972

Coloured Greys 2 © Bridget Riley 1972

Bridget Riley

112 works

Bridget Riley is one of the greats of British Modern art, famed for pioneering the 'Op Art'— optical art— movement that took off in the 1960s, reflecting the vastly trendy 'mod' culture that began in London and other British cities. And while Bridget Riley's paintings and prints were hugely influenced by her serene upbringing in coastal Cornwall, the artist has since worked and gathered inspiration from an area that spans hemispheres: from New York to Egypt, London to Cote D'Azur and back. In this article, we take a journey through some of the most significant places that have shaped Bridget Riley's artistic career.

Serenity in Cornwall: Bridget Riley's wartime upbringing

Bridget Riley (b. 1931) was born in Norwood, in the south London borough of Croydon. When Riley was just 8 years old, World War II broke out, and the women of the family—Bridget Riley, her sister, mother and aunt—moved to a family house near Padstow, a coastal town in Cornwall. The five years that Bridget Riley lived in Cornwall were formative for the soon-to-be painter: war shaped her awareness of gender, her future education and her appreciation for nature. Given the comparative isolation of the Cornish cottage, as well as the lack of transport due to the war rationing of petrol, Riley had little choice but to soak up the beauty of the coastal landscape, free of external distractions such as school.

The beauty of Cornwall made for a long-lasting impression on Bridget Riley, influencing the sunny blues, greens and wildflower pinks of her artistic palette. Nowhere is this impact more evident than in her Lozenges series, which has at its heart Riley's formulaic pattern comprising organic shapes, generated by the intersection of diagonal stripes and wavy verticals. This pattern is evocative of the rhythm and ceaseless variation of waves; Riley recalls being astonished from an early age by the fact that waves "will never be the same again each and every time they’re different, every single wave every single ripple, every single breaking of a wave on a shore or rock all are unique and have never happened before and will never happen again." Passing By and Going Across are two works that especially emphasize this transience through their titles, as well as sharing clearly nature-inspired palettes.

Coming of age in the wake of World War II, Riley also benefitted from the liberation of women from solely domestic roles as a result of their contribution to war efforts. In a 2018 interview with The Financial Times, Bridget Riley stated,

"I was extremely fortunate growing up during the second world war, from that point of view. Gender differences absolutely did not operate, and comradeship was very intense....After the war we all wanted to do something with the peace. It sharpens you. In 1949 I went off to study at Goldsmiths College wearing a pair of corduroy trousers and a man’s shirt. None of this gender business occurred to me!"

Both Riley's mother and her aunt had studied at Goldsmiths College before her, helping to cement her path to becoming an artist.

Bridget Riley studies in London: Goldsmiths, RCA, Whitechapel

Bridget Riley moved to London to study art at Goldsmith's College in 1949 and subsequently at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1952. Perhaps surprisingly, Riley did not graduate from Goldsmiths, because she insistently only attended her drawing classes and later, though she graduated from the RCA, she was unable to attend the ceremony as her father suffered an accident, and she returned home urgently to care for him. Despite this, her time in London played a huge role in helping Riley formulate her pioneering Op Art style, and Riley has since been made an honorary graduate of Goldsmith's.

A 1958 Jackson Pollock exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery had a particularly lasting impact on Bridget Riley. Though Riley is explicit in interviews about not using the term abstract painting to describe her art, Whitechapel Gallery's active promotion of the American Abstract Expressionists at that time served Riley with inspiration, his wild, colourful drip paintings furthering her desire to work with the optical effects of colour and pattern.

1960: Riley Tours Italy

In the summer of 1960, Bridget Riley and then-partner Gerald de Sausmarez embarked on a summer journey to Italy where they took in the sights, painted artworks, and visited galleries. It was here that Bridget Riley's unique style began to take shape, dividing her oeuvre into two stylistic poles of work: the figurative, still heavily Impressionist painting, Pink Landscape, and the first of the now iconic Bridget Riley black and white paintings.

Still holding onto the inspiration of pointillists such as Georges Seurat, Pink Landscape (1960) is luscious, comprised of a rich spectrum of dots that create hue compositely. It is a perfectly academic painting and shows Riley's promising mastery of colour, which would later form the basis of her Stripe paintings.

Yet, beside the stark modernity of the first black and white paintings that she began later that same year, the painting looks positively quaint. Riley, having suffered an upsetting split from de Suasmarez, and still in crisis following her father's accident and the abrupt end to art education, began painting in a style that broke sharply away from the past, creating edgily monochromatic and geometric works that have since made her a fixture of modern art.

Image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960

Image © Sotheby's / Pink Landscape © Bridget Riley 1960Flavours of France: Bridget Riley Learning from Seurat

Around this time, Bridget Riley had been making many imitations of the Impressionist paintings of French artist Seurat; she took a trip to Paris, and spent time recreating Georges Seurat's The Bridge at Courbevoie (1886–87), both of which (Seurat's original and Riley's version) featured centrally in the Courtauld Gallery's 2015-16 exhibition, Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat.

After Seurat’s The Bridge at Courbevoie © Bridget Riley 1959

After Seurat’s The Bridge at Courbevoie © Bridget Riley 1959It was perhaps because of this still-ignited fascination with French impressionism that Riley and her partner visited the Vaucluse Plateau, in the South East of France, in 1961, and bought a dilapidated farm that would eventually be converted into Bridget Riley's studio. Even having moved away from figurative painting for the vast breadth of her career, Bridget Riley always retained one thing in common with Georges Seurat (b. 1859): both artists had a love of water, and especially focussed on it's prismatic reflection of light in a sunny climate. Where better for Riley to pursue this visual love than France's Cote D'Azur?

1961-65: Bridget Riley takes New York by storm

Riley's crucial breakthrough moment is generally attributed to her painting of Movement in Squares in 1961. Returned to London and deflated, the creation of Movement in Squares saw the artist stripped back to only the most essential resources by artistic and personal crisis, nevertheless creating breathtaking art. Using only the most basic geometry, squares, and black and white to disorienting effect, the work shows a monochrome checkerboard seemingly disappearing into a vertical fold.

From this success, Riley's confidence in her pioneering new way of working—involving extensive calculation, measuring and planning works before executing them in paint—grew and so did her fame. Movement in Squares was acquired by the Arts Council Collection just a year after it was created, and that same year it became a central staple in her print oeuvre, also, with the creation of the original screen print titled Untitled (Based On Movement In Squares). Today, it remains Bridget Riley's exemplary work and thus is endlessly popular among art collectors.

Want to learn more about Bridget Riley's most iconic and investable prints? Read our latest Bridget Riley Market Watch here.

Following on from the success of her Movement works, in 1965, Bridget Riley was a participating artist alongside other key names such as Victor Vasarely and Josef Albers in the exhibition “The Responsive Eye”, curated by William C. Seitz, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It was a dramatically successful and frustrating year for Bridget Riley and the Op Art movement as a whole: while the Museum of Modern Art exhibition was incredibly successful with the public, this success led to the almost instantaneous replication of Riley's modern art across the fashion world without the artist's permission. Bridget Riley attempted to take action against certain brands and designers but to no avail.

New York had cemented her place as a household name and artistic celebrity, but it had also left her disillusioned. Though it is impossible for any but the artist to know, perhaps it was this early disappointment that has led Riley to lead an uninvolved public life, rarely doing interviews and never attempting to monopolise on the fashion-forward appeal of her Op Art.

1970s: Bridget Riley's Egyptian Palette

Having travelled to Venice in 1968 as Great Britain's representative, where she became the first woman awarded the International Prize for Painting, through the 1970s, Riley continued to travel and garner inspiration from many different places. The most critical destination, however, was Egypt.

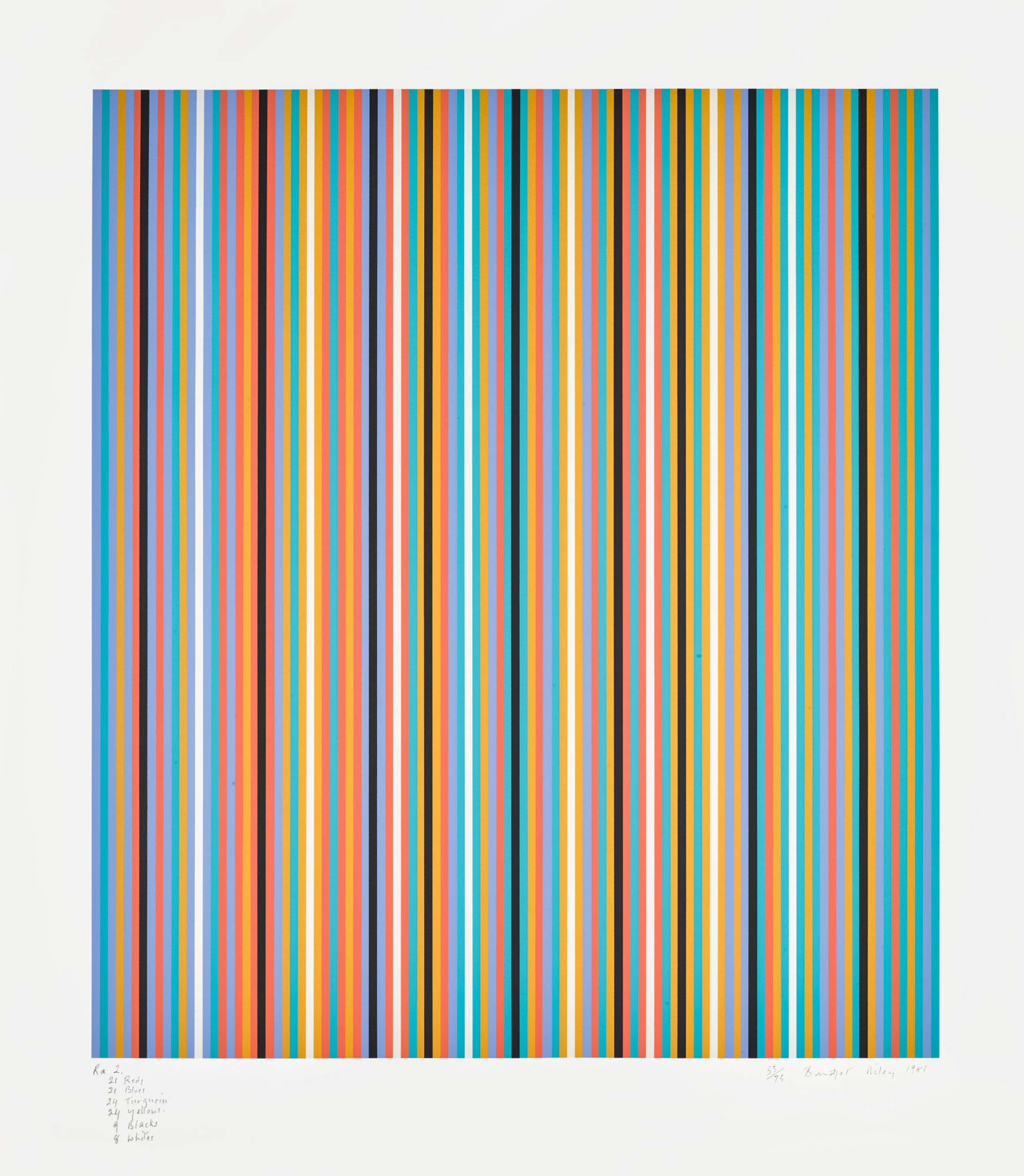

Bridget Riley travelled to Egypt in 1980–81 where she established her iconic 'Egyptian Pallette'. This was a selection of five colours (initially three) inspired by the colours of the local surroundings and of the ancient Egyptian art she saw there, including the colours of hieroglyphs on tombs. She restricted herself to replicating these colours from memory, suggesting the extent to which they had a synaesthetic relation to the place itself for Riley. Indeed, her works from the Egyptian Cycle, including the Ka and Ra painting series, speak for themselves about the heat, light, and sharp shadows of Egypt.

She was fascinated by the ubiquity of the colours across Ancient Egyptian life— from everyday settings to the crypts of the Pharoahs— and the vivacity of her works reflect the Egyptian culture's worship of life and fertility. Arguably the most famous of the Bridget Riley paintings from this period is Achæan, owing perhaps to the fact the painting is owned and displayed by Britain's Tate Gallery.

Bridget Riley created many prints from this period, many of which can be found in MyArtBroker's Stripes collection, including Achæan, Ra (Inverted) and Ra 2.

Present Day: Cornwall, London, France, Rome

Today, Bridget Riley works from her three studios in Cornwall, London and France, a balance of locations that likely provides her plenty of year-round sunlight. Given the importance of colour to her work, it is not a surprise that she only works in natural daylight, nor that she retains a residence abroad, where she can escape to sunnier skies.

According to Kettle’s Yard's Lindsay Millington, Bridget Riley's London house is a brilliant reflection of the artist's present day practice: "her uncompromising commitment to modernity becomes clear when I enter the spacious ground-floor room. Vibrant paintings alive with striped colours pulsate on the white walls." As well as expansive retrospectives, that reflect Bridget Riley's status as a foremost British contemporary artist, Riley continues to produce work.

At 92, Riley unveiled her first ceiling installation at the British School in Rome, an original piece inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. This artwork masterfully combines her signature optical stripes in blue, red, white, orange, and lilac, reflecting a harmonious blend of classic and modern art. Riley's innovative spirit shines through, redefining visual storytelling by intertwining traditional art with contemporary flair.

These days that work is often vast wall-art, such as she has in her own home, that returns to her motifs from her oeuvre (notably Nineteen Greys and Stripes) on a new scale. In 2019, for example, The National Gallery in London unveiled a vast 10x20 metre work, created directly onto the white wall by Bridget Riley, called Messengers. Inspired by the turn of phrase of another British great, John Constable, when referring to clouds, Messengers encapsulates the Britishness of Bridget Riley: though she has painted in many different places throughout her life, it has always been under the same mesmerizing sky. She has given endlessly to British culture and contemporary art, and acknowledges with gratitude the rich British pastoral tradition and landscapes that inspired her initially.

Image © The National Gallery 2019 / Installation view of Messengers with Bridget Riley and Director Gabriele Finaldi at The National Gallery

Image © The National Gallery 2019 / Installation view of Messengers with Bridget Riley and Director Gabriele Finaldi at The National GalleryCheck out our latest Modern British Prints Market Report for valuable insight into the 2023 performance of Bridget Riley’s art as financial asset, alongside market analysis of other renowned British artists.