Gazing

Ball

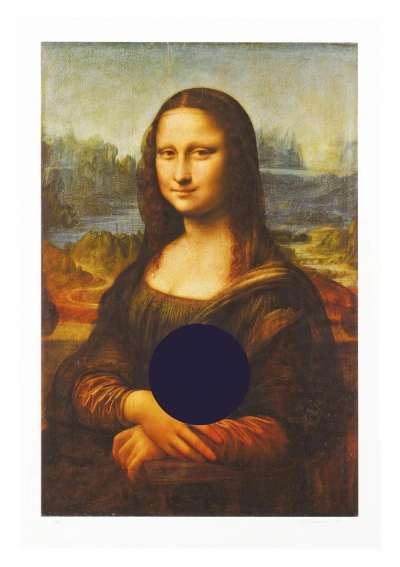

Jeff Koons’ Gazing Ball series continues his appropriation of imagery from all cultural arenas, here, transforming highly-regarded paintings— such as Tintorettos and Botticellis—by adding metallic-blue orbs, reflecting the gallery in which the viewer stands. Koons’ orb punctuates our sense of familiarity and offers an ironically oblique opportunity to descry our cultural heritage.

Jeff Koons Gazing Ball For sale

Gazing Ball Value (5 Years)

Sales data across the Gazing Ball series by Jeff Koons varies by print. While standout works have sold at auction for up to £60000, other editions in the series remain rare to market or have yet to appear publicly for sale. Of those tracked, average selling prices have ranged from £60000 to £60000, with an annual growth rate of 4.51% across available data. Collectors should note the discrepancy in performance between more visible and lesser-seen editions when considering value potential in this series.

Gazing Ball Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gazing Ball (Da Vinci Mona Lisa) Jeff Koons Signed Print | 19 Apr 2022 | Phillips New York | £25,500 | £30,000 | £40,000 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

Throughout the length of his long and illustrious career, American artist and ‘king of kitsch’ Jeff Koons has been no stranger to controversy. Whether it be catalysed by his sustained use of so-called ‘art fabrication’ – a divisive artistic methodology pioneered by the likes of Pop Art icon Andy Warhol and involving the extended use of third parties as a means to realise one’s artistic projects – or the pornographic photography series, Made In Heaven (1990-91), the markedly provocative ‘edge’ by which both the artist’s work and personality can be characterised has served to split opinion, on the one hand, and inflate his works’ monetary value on the contemporary art market, on the other. Whether crass, opportunistic, or consistent with artistic genius, there is little doubt, however, that the first appearance and subsequent development of Koons’ œuvre constitutes a decisive moment in Contemporary art history. This fact is certainly only confirmed by the so-called Gazing Ball series, which Koons began in 2013. Comprising sculptures, found objects, and paintings, it embarks on the bold appropriation – or ‘détournement’ – of a wealth of art historical cultures.

Intervening in the highly-regarded works of Tintoretto, Vélasquez, El Greco, Manet, Pablo Picasso, Botticelli, and Boucher, the series suggests either Koons’ grandiose self-positioning within art historical genealogy, his cynical appropriation of established art culture, or indeed both. The thinly-veiled reference made by Gazing Ball (stool) to French artist Marcel Duchamp – a hugely influential figure whose distinctly avant garde work and then controversial artistic methodologies are no doubt one of the most central points of reference for those utilised by Koons himself – is perhaps the most significant example thereof. Bearing striking resemblance to the now iconic and revolutionary 1913 work, Bicycle Wheel, a so-called ‘assisted Readymade’ work comprising a bicycle heel mounted atop a household stool, Gazing Ball (stool) takes a similarly quotidian stool and adorns it with a metallic bauble – or ‘gazing ball’ – the surface of which recalls some of the artist’s most well-known sculptures, such as Hanging Heart (1995) and Balloon Dog (1995).

Works such as Gazing Ball (Titian Mars, Venus, and Cupid) engage in a similar mode of reappropriation, recreating iconic paintings with a spectacular level of detail and fidelity and punctuating their surface with a 3-D, mirror-like ball. These part-painterly, part-sculptural aspects of the Gazing Ball series, of which Gazing Ball (Da Vinci Mona Lisa) (2016) is a standout example, are ‘not about copying’, Koons has argued. Like his metaphysically challenging installation works, such as One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (1995), these pieces are much more complex than first meets the eye. Commenting on the subversive works, Koons has commented, “it’s been an ongoing journey of becoming, and of having a greater sense of self […] I’d like to think of it as my own cultural DNA; these are very iconic paintings, they’re kind of the canon of western art history, the ball is completely reflective… so it’s telling you everything it can about where you are in the universe at that moment.”