Easyfun

Jeff Koons’ 200- Easyfun series comprises several painterly, Dadaist collages. Containing three original digital prints, the works allude to the garish, saturated world of popular culture in their assortment of well-made-up facial features—eyelashes, lips, and hair— random food items—sweetcorn, American breakfast cereals, glacé cherries—and cartoon-like, Disney-esque features.

Jeff Koons Easyfun For sale

Easyfun Value (5 Years)

Jeff Koons's Easyfun series has historically shown more modest results compared with the artist’s wider oeuvre, with auction prices ranging from £413 to £3074. Average annual growth has remained modest at -0.37%, with certain works seeing declines in value. Over 16 total auction appearances, average selling prices have held steady around £1441. This series appeals to collectors seeking accessible entry points into Jeff Koons’s print market.

Easyfun Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lips Jeff Koons Signed Mixed Media | 16 Mar 2023 | Forum Auctions London | £340 | £400 | £550 |

Loopy Jeff Koons Signed Print | 26 Sept 2018 | Forum Auctions London | £2,210 | £2,600 | £3,300 |

Hair Jeff Koons Signed Print | 20 Nov 2010 | Phillips New York | £2,253 | £2,650 | £3,500 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

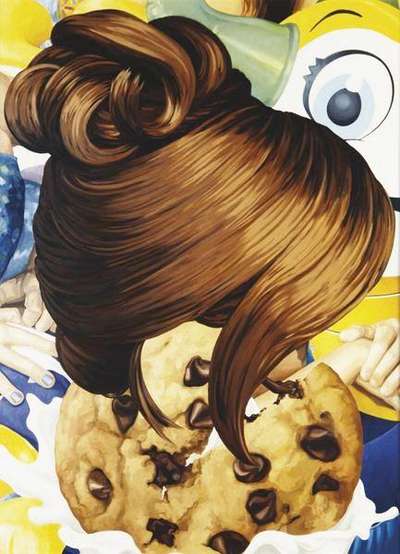

The Easyfun series comprises several painterly works by controversial American artist and king of self-promotion, Jeff Koons. Although well-known for his sculptural works, which often engage in a tongue-in-cheek repurposing of everyday objects – a now-common artistic practice pioneered by French Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp – this series comprises three original prints. Grouped together due to their visible connection to Koons’ official 1999 Easyfun series, these digital works are testament to the artist’s playful and almost childlike approach to making art; entitled Hair (1999), Loopy (2000) and Lips (2012), they depict a number of subjects (and objects), each plucked from the garish, saturated world of popular culture. Arranged in an over-the-top and almost Baroque fashion, eyelashes, lips, and women’s hair share a stage with sweetcorn, American breakfast cereals, glacé cherries, and cartoon-like features reminiscent of those created by the cultural conglomerate, The Walt Disney Company.

In 2002, Koons unveiled a series which built upon the original Easyfun works (1999), which he entitled Easyfun-Ethereal. Tracing a genealogy through Koon’s artistic production during this period, these seven large-scale works, which made use of then-revolutionary computer-aided design technologies, were commissioned for Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin. Bearing visible debt to large-scale billboard advertisements, the profound influence of which Koons has acknowledged, these pieces are imbued with a very tangible sense of consumerist excess; visual translations of an effervescent romp through contemporary culture that references the work of the likes of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, as well as the American Pop Art movement’s pre-occupation with all things quotidian, they are designed to somehow empower the viewer, instilling within them a feeling of childlike confidence which directly mirrors their form. Commenting on the Easyfun-Ethereal works, Koons once said, “I’ve worked with things that are sometimes labelled as kitsch; but I’ve never had an interest in kitsch per se. I always try to give viewers self-confidence – a foundation within themselves. For me, my work is more about the viewer than anything else.”

Koons remains a highly controversial and divisive figure in the international art scene. With these particular works, it is once again easy to see why. Lambasted as puerile, reductive, and overwhelmingly concerned with his work’s material value, Koons is sometimes regarded as the foremost disciple of the father of Pop Art, Andy Warhol, many Koons-Warhol comparisons derive from the fact that the former often employs expert craftspeople or a large team of studio assistants to create artworks on his behalf, a practice made famous at Warhol’s studio, The Factory, during the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Like his personal friend, British artist Damien Hirst, Koons has worked according to a ‘paint-by-numbers’ technique that has seen a vast number of assistants adhere to a strict taxonomy of colour, chosen by Koons himself, when producing works on his behalf. With the Easyfun series, ‘art fabrication’, as this practice is known, is tangibly present, with each work in question having been painted by one of Koons’ assistants according to the same process. One work in particular – Lips – recalls Hirst’s so-called ‘Spin’ paintings, such as Beautiful Mickey (2012); produced in the same year, the work bears the hallmarks of its creator’s awareness of the art market, and those often-borrowed artistic styles that are both easy to reproduce, and likely to generate further interest and revenue.