Celebration

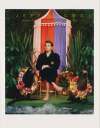

Jeff Koons’ Celebration prints commemorate the works that made him international fame. Begun in 1993, the original Celebration comprised 16 monumental sculptures and 16 photorealistic paintings— including his Balloon Dog, Diamond and Ribbon. The series references archetypal life milestones, as well as enigmatically, events from Koons’ own biography.

Jeff Koons Celebration For sale

Celebration Value (5 Years)

Jeff Koons's Celebration series has historically shown more modest results compared with the artist’s wider oeuvre, with auction prices ranging from £4921 to £12808. Average annual growth has remained modest at -3.23%, with certain works seeing declines in value. Over 14 total auction appearances, average selling prices have held steady around £7376. This series appeals to collectors seeking accessible entry points into Jeff Koons’s print market.

Celebration Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pink Bow Jeff Koons Signed Print | 19 Sept 2024 | Phillips London | £4,250 | £5,000 | £7,000 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

The word ‘celebration’ references divisive American artist Jeff Koons’ large-scale series of the same. Begun in 1993, Celebration comprises 16 monumental sculptures and 16 photorealistic paintings, and brings together some of Koons’ most iconic creations – each of which he has named his ‘celebrations’. According to the artist, each element in the series references one of life’s milestones, with balloons (Balloon Dog, Balloon Flower), Cake, Ribbon, Diamond, a Party Hat, and even Easter eggs (Bread With Egg) making an appearance. Although not immediately obvious, the series has its origin in the ups and downs of Koons’ personal life. In the early 1991, the artist and his then wife Ilona Staller – who, alongside Koons, had been the subject of the highly-controversial Made In Heaven (1989) series, first exhibited at the 1990 Venice Biennale – had a son named Ludwig. Later, in 1993, Koons and Staller separated, with Staller taking their son with her to Rome. As such, each of Koons’ so-called ‘celebrations’ – objects which are, in effect, constitutive of large-scale toys – were conceived as monuments symbolising the artist’s yearning for the return of his son.

Commenting on the series, Koons once remarked, “I think all art involves out of some autobiographical aspect. It was a period when I was kind of losing trust in humanity, I felt everything that was right was kind of made ‘wrong’. But I held on through my work.” Works such as Pink Bow (1995), a brightly coloured and photorealistic depiction of the named subject, contain a childish innocence that reference the early years of Koons' young family, two-thirds of which was now living in Rome, whilst he remained in New York; Hanging Heart (1995) and Balloon Dog (1995) exude a sense of the artist’s desire to win over his ex-wife and child, now frustratingly distant, and have them return to be with him. Incidentally, these two sculptural pieces are some of Koons’ most famous works; 5 iterations of each were created, their mirror-polished stainless-steel surfaces adorned with a different transparent colour coating.

Much like the rest of Koons’ wider œuvre, the ‘celebrations’ were created by a large team of art assistants and master craftspeople from around the world according to a strict taxonomy of colour and design chosen by the artist himself. For Balloon Dog and Moon, Koons enlisted the help of Carlson & Company, a California-based fabrication and engineering firm, and Arnold, a similar outfit located in the German city of Frankfurt. The realisation of the series involved an enormous amount of money, and it has been reported that several foundries went bankrupt trying to realise works Koons had commissioned them to create during this period. Even at this early stage in the artist’s career, this practice – sometimes named ‘art fabrication’ – saw Koons regarded as the Contemporary Art world’s foremost disciple of the godfather of Pop Art, Andy Warhol. Characteristic of a period of intense self-reflexion and artistic reinvention, which saw Koons transition from producing smaller to larger-scale works, the Celebration series was instrumental in re-affirming Koons’ controversial public persona. Commenting on the series, friend and contemporary Damien Hirst confessed he had once heard that Koons had “put 35,000 man hours of polishing into Cracked Egg and then decided he didn’t like it and scrapped it.”