The Jean-Michel Basquiat Forgery Scandal at the Orlando Museum of Art

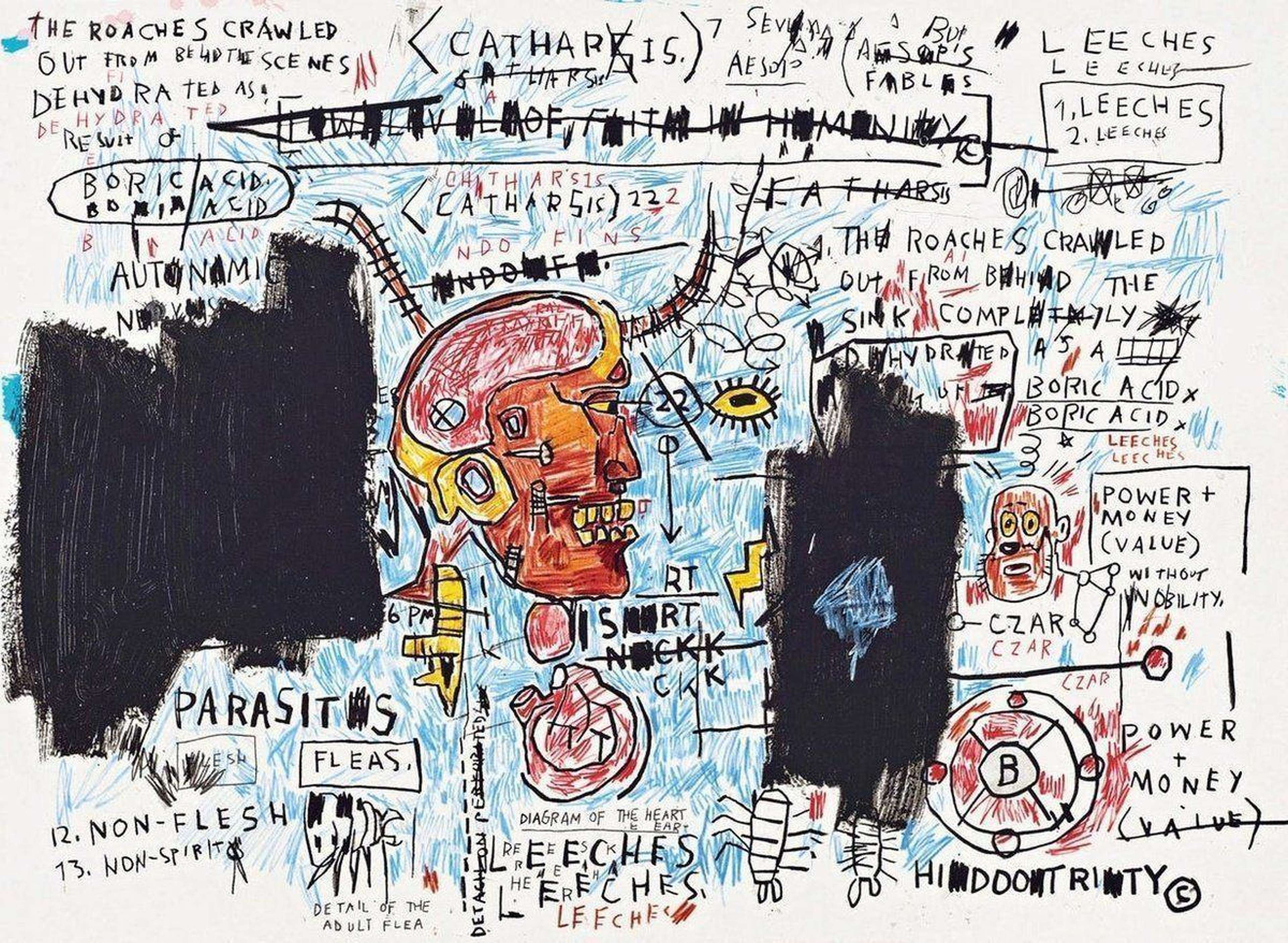

Image © Youtube / Basquiat Heroes & Monsters Exhibit

Image © Youtube / Basquiat Heroes & Monsters Exhibit

Interested in buying or selling

Jean-Michel Basquiat?

Jean-Michel Basquiat

59 works

To many viewers, art stands as a testimony to the pinnacle of human creativity and expression. Culturally, museums are often seen as sanctuaries where history, art, education and aesthetics converge. Yet, even in this revered space, the world of art is not untouched by deceit and duplicity. With their intricate craft of imitation, forgeries have time and again cast shadows over the authenticity of masterpieces, raising uncomfortable questions about value, veracity and the very nature of art itself. The recent uproar surrounding the Basquiat forgery scandal at the Orlando Museum of Art is a poignant reminder that even esteemed institutions are not immune to the pitfalls of fraudulence. Whether it happens in a large or small scale, it is imperative to understand that when it comes to forgery, the stakes are not just monetary but also involve the integrity of art history and the trust of art enthusiasts worldwide.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / The Orlando Museum of Art 2012

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / The Orlando Museum of Art 2012Backdrop to a Scandal: The Orlando Museum of Art

The Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) was established in 1924, it has proudly served its community for close to a century, and has since become “a leading provider of visual art education and experiences in a four-county region”, playing an instrumental role in enriching the region with art and culture. At its core is a vast and diverse collection, encompassing various periods and styles, from African and Ancient American art to contemporary American graphics. The OMA also has a bustling temporary exhibition calendar that aims to spotlight emerging local talents and globally revered artists alike. Beyond its objects, OMA is celebrated for its expansive educational endeavours, offering programs that resonate with children and adults and fostering engagement with art in myriad ways. Further adding to its prestige is its accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums, which hopes to attest to its unwavering commitment to museum excellence.

At the time of the Basquiat Heroes and Monsters show, its director was Aaron de Groft, who had previously worked at the Muscarelle Museum of Art. De Groft had a previous record of unconvincing authentications, including the controversial purchase of an alleged Paul Cézanne and a dubious attribution of an artwork to Titian. During his tenure at Muscarelle he doubled the collection by purchasing previously unremarkable paintings from the 16th century to the 19th century at auctions for low prices, before attributing them to famed artists. Only a month before the opening of the Basquiat show, De Groft cancelled a planned lecture on a work by Jackson Pollock after questions were raised about its authenticity.

The Challenge of Authentication and the Closing of the Basquiat Estate Committee

Authenticating artworks is a complex endeavour, a melding of science, history and human interpretation, each bringing its own set of challenges. The stakes are high, not only in terms of the monetary value of the artworks but also in terms of the reputation and credibility of the artists, collectors, galleries and institutions involved. As technological strides are made, forgers too have evolved, harnessing sophisticated methods to craft art pieces that can fool not only the untrained eye but also certain scientific analyses. While insightful, tools like radiography or pigment analysis have their limits, especially when confronted with forgeries made using period-appropriate materials and knowledge. Navigating the maze of historical documentation is equally intricate, with many older artworks presenting gaps in their ownership records, while some unscrupulous sellers might even concoct false provenance documents.

Beyond these technical and historical hurdles, however, also lie the nuanced pressures and influences of human nature. The tantalising prospect of immense profit can sometimes overshadow objective judgment, especially since the art world is not known for being immune to the allure of prestige; institutions and collectors may occasionally be blinded by the desire to associate with a masterpiece, even if its origins are questionable. This can sometimes be further complicated by the endorsements of art world specialists and, occasionally, lapses in due diligence may occur – be it from overconfidence, constraints of time, mere oversight or actual malice.

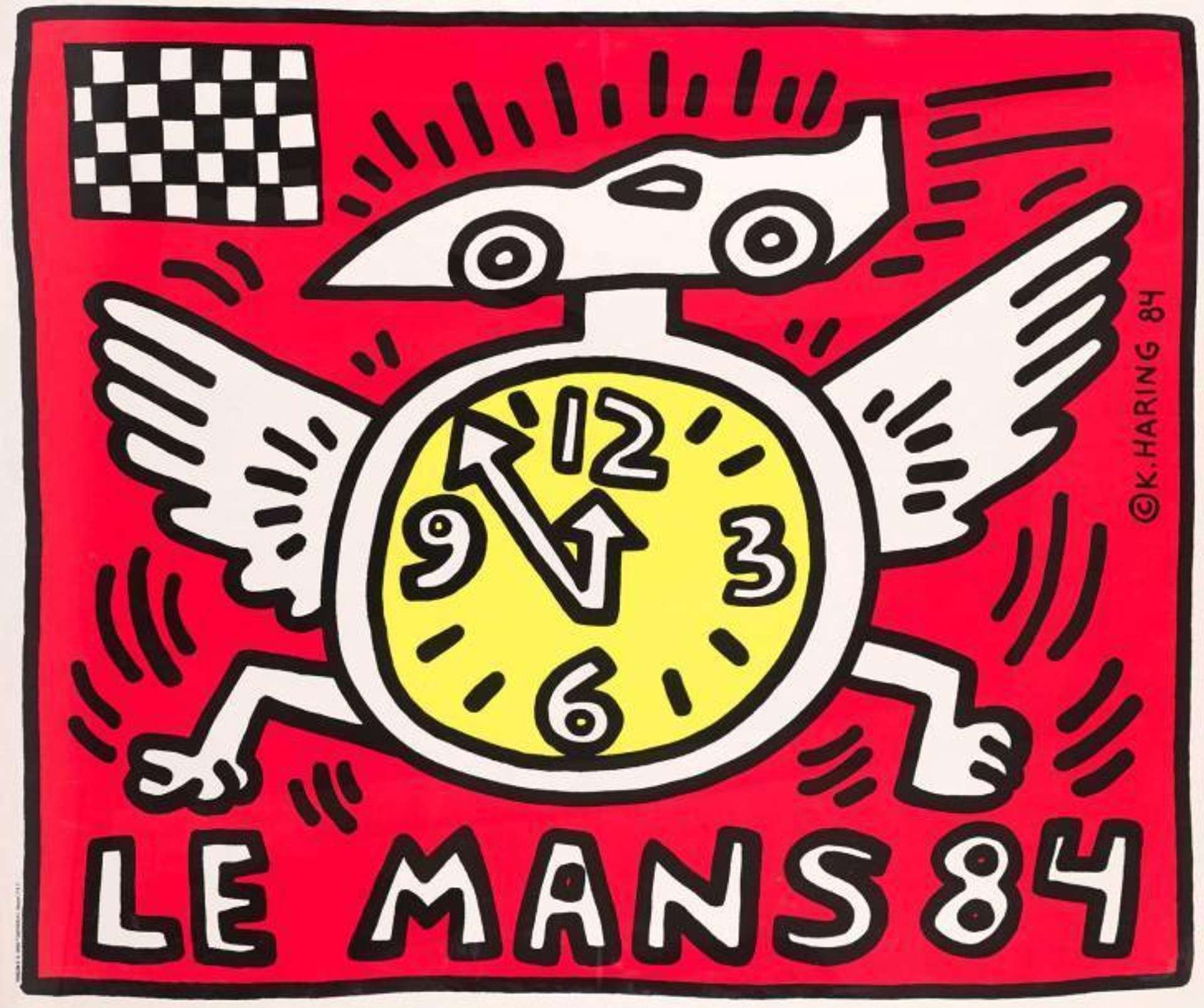

To prevent forgeries and misattributions, important artists often leave an estate following their death. An estate’s purpose is to protect and enhance the artist’s legacy, largely by acting as a source of information for scholars and institutions and by maintaining the integrity of the artist’s market. The latter requires an authentication board, which the estates of Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Keith Haring all had at some point. These committees acted as the ultimate authorities in conferring authenticity, but most of them no longer exist due to legal battles and complications. In Basquiat’s case, the board existed for over eighteen years and was led by the artist’s own father, who was an accountant by profession and struggled with the machinations of the art world. The Basquiat authentication committee was disbanded in September 2012, leaving space for more forgeries and artworks of dubious provenance to enter the market. Nevertheless, all authentic artwork should have a full record of documentation that should survive the proof of due diligence.

At the heart of it all, the very subjectivity of art can play tricks on the mind. The thrill of unearthing an undiscovered work by a legendary artist can lead to wishful thinking, and personal biases might inadvertently tint professional judgment. On top of all these intricacies is the looming threat of potential lawsuits if an authentication adversely affects an artwork's value and the often unspoken yet palpable pressures from institutions seeking increased footfall and sponsorship.

Heroes and Monsters: The Collection's Purported History

The show Heroes and Monsters was composed of 25 cardboard works purportedly created in 1982, considered by many to be the year of Basquiat’s big break. Supposedly, the artist created these while living in Larry Gagosian’s home in Los Angeles, and sold the pieces directly to television screenwriter Thaddeus Mumford, Jr without Gagosian’s knowledge. Following this alleged purchase, the works disappeared, apparently languishing in Mumford’s storage unit until 2012, when its contents were auctioned off following lack of payment. After being “recovered”, the works were sold shortly before Mumford’s death in 2018. When put on display at the Orlando Museum of Art, director De Groft claimed the paintings were worth over £100 million.

There were many holes in the story even before the show opened. Firstly, Mumford was never an art enthusiast or a collector, and in 2017 signed a declaration to the FBI claiming he had never met Basquiat or purchased his work. Gagosian, a major player in Basquiat’s early career, said he found “the scenario of the story highly unlikely”, a position echoed by many experts on the artist. Perhaps most glaringly, one of the works was painted onto the back of a shipping box with a FedEx label – one that only came into usage in 1994, twelve years after the works’ purported creation date and six years after the artist’s death.

Nevertheless, De Groft had some experts on his side. He cited handwriting expert James Blanco’s certification of Basquiat’s signature, a 2017 analysis by Basquiat expert Jordana Moore Saggese and signed 2018-2019 statements by Diego Cortez, an early supporter of Basquiat and member of the artist’s now-dissolved authentication committee. Other key players in the story included Los Angeles auctioneer Michael Barzman, storage hunter William Force and financial backer Lee Mangin, all of whom collaborated in the chain of custody of the works. The paintings had previously repeatedly failed to sell on the secondary market due to their dubious provenance.

According to the New York Times, even the curatorial staff at the museum expressed concerns about the authenticity of the works. Furthermore, the FBI had issued a subpoena to the museum in July 2021, demanding to see all communications between the museum’s employees and the works’ owners. According to a later affidavit, De Groft sent a threatening email to the expert Saggese after she claimed she no longer wanted to be associated with the exhibition. It read: “You want us to put out there you got $60 grand to write this? OK, then. Shut up. You took the money. Stop being holier than thou.” Amidst all this uncertainty, the show went on, with De Groft insisting on their legitimacy.

From Suspicion to Seizure: A Timeline of the Unravelling

The exhibition opened to the general public on February 12th 2022, after several months of delay. It was immediately popular, with thousands of visitors coming in its opening weekend and attendance only increasing from then. It was originally meant to stay through June 30th 2023, but after questions of legitimacy were raised OMA announced it would close exactly one year earlier and travel to Italy. Instead, only four days after opening, on February 16th, the New York Times published an exposé openly questioning the authenticity of the works. On June 24th, the FBI raided the museum, removing every single artwork from show. Four days later, on June 28th, De Groft was fired from the museum. By that point, all mentions of the exhibition had been scrubbed from the museum's website and social media.

The Fallout

The museum emerged from the scandal with its reputation in tatters. The crisis deepened as many members of the museum’s board of trustees refused to resign, and an external law firm was called in to conduct a review. It then emerged that many of the figures involved in the works’ transaction had criminal records, including Force and Mangin. The latter had previously been involved in a number of questionable dealings, including drug trafficking and stock manipulation. The chairwoman of the board, Cynthia Brumback, was forced out of her role in December 2022, and the museum was put on probation by the American Alliance of Museums in January 2023.

There were no updates on the investigation until April 11th 2023, when the United States attorney’s office charged the auctioneer Barzman for making false statements to the FBI. It emerged that he and an accomplice forged all of the artworks in 2012, before placing them for sale on eBay. In the August 2023, the Orlando Museum of Art sued De Groft for fraud, breach of contract and conspiracy. The lawsuit stated he had agreed to exhibit the fake Basquiats without ever inspecting them in person, and only travelled to see them three months before Heroes and Monsters opened. Furthermore, it claimed “De Groft capitalised on OMA's reputation and financial resources to gain personal fame and notoriety from his role in these business transactions as a 'discoverer' of found art.” The disgraced director denied having any financial arrangement with the works’ owners – despite the fact that in a 2022 e-mail included in the filing, he demands 30% of the future sale of a Titian set to be exhibited at OMA.

The legal case is still ongoing.

Rebuilding Trust: Lessons From the Orlando Museum Controversy

In the aftermath of the Orlando Museum Basquiat controversy, the art world found itself at a crucial crossroads, grappling with the duality of its love for “undiscovered” masterpieces and the shadows of deceit that sometimes accompany them. The scandal serves as a poignant reminder that, even within the halls of cultural institutions, the allure of prestige and profit can sometimes eclipse rigorous due diligence. However, from such challenges also arise opportunities for reflection and growth. As the dust settles, the foremost lesson is the imperative of transparency, bolstered by rigorous research and objective appraisal.

The responsibility falls not just on museums but on the entire art ecosystem, from dealers to auction houses, experts to enthusiasts. Authenticity, in both art and intent, is the cornerstone upon which trust is built. As institutions like the Orlando Museum of Art move forward, it is this commitment to authenticity that will help rebuild lost trust, ensuring that art remains a beacon of human expression untouched by the tarnish of doubt. The journey ahead may be demanding, but the stakes – the very integrity of the art world – are too high for anything less than unwavering dedication.