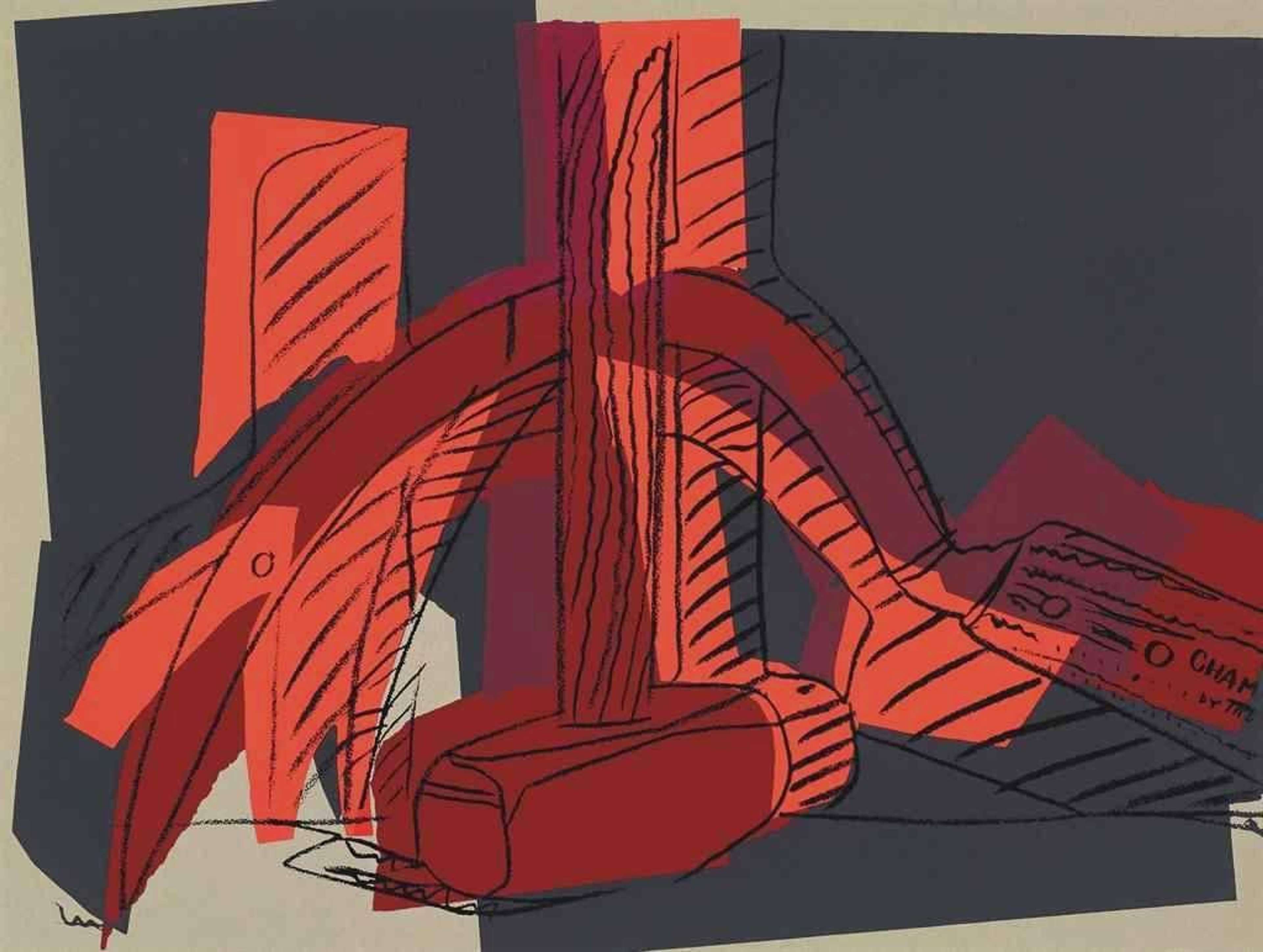

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1977

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1977

Interested in buying or selling

Andy Warhol?

Andy Warhol

493 works

The series appropriates the communist symbol.

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1977

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1977The hammer and sickle is the quintessential communist symbol. Representing proletariat solidarity, the symbol was first adopted during the Russian Revolution. With the hammer representing the workers and the sickle representing the peasants, this is one of the most ubiquitous political symbols in modern history. Indeed, it might seem strange that Warhol - the King of Pop and champion of consumerism - should choose to depict the symbol of communism. However, Warhol's interest lay primarily in the nature of mass media and collective visual memory. There was perhaps no symbol more fitting of Warhol's attention than the hammer and sickle, hence this extensive foray into the Soviet motif.

The series presents the ultimate antithesis to capitalism.

Campbell's Soup I (complete set) © Andy Warhol 1968

Campbell's Soup I (complete set) © Andy Warhol 1968Warhol's Hammer And Sickle series is perhaps the ultimate antithesis to his entire ethos. The premise behind Warhol's Pop was capitalism, exploring the imagery perpetuated by mass media to sell products to the populous. As we see in his Campbell's Soup and Brillo Box series, Warhol was committed.

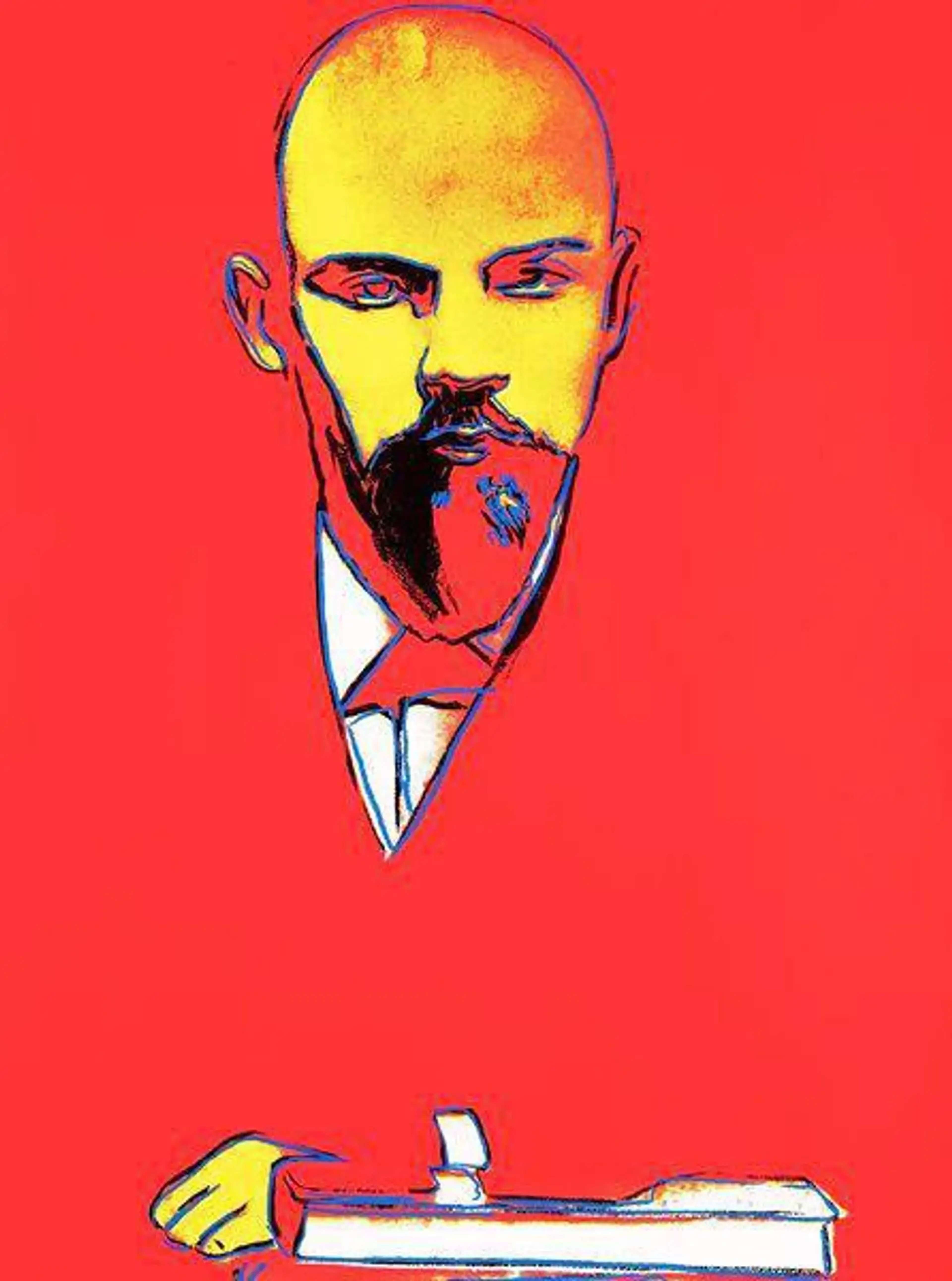

Warhol also depicted leader of the Communist Party, Vladimir Lenin.

Black Lenin (F. & S. II.402) © Andy Warhol 1987

Black Lenin (F. & S. II.402) © Andy Warhol 1987Warhol’s Lenin series captures the Communist Party leader Vladimir Lenin with an intense, imposing presence, using striking colors that evoke the style of political propaganda. Created in 1987, just before Warhol’s death, the series reflects a departure from his usual vibrant overlays, instead employing a limited palette to highlight Lenin’s face and form against red and black backgrounds. Though initially drawn to fame and celebrity, Warhol occasionally explored political themes, as with this portrayal of Lenin, as well as other leaders like Chairman Mao and JFK. The Lenin portraits, especially the renowned red version, use bold contrasts to emphasise Lenin’s gaze and authority.

The Hammer and Sickle represents industrial and agricultural workers.

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.63) © Andy Warhol 1977

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.63) © Andy Warhol 1977Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle series reinterprets this symbol of Communism through the lens of mass production. Inspired by graffiti he saw in Italy during the 1970s, Warhol chose to feature the iconic image of the hammer and sickle, representing industrial and agricultural labor.

Warhol treated the Hammer and Sickle like a still life.

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.61) © Andy Warhol 1977

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.61) © Andy Warhol 1977Rather than using a flat, traditional design, Warhol styled the Hammer and Sickle as a still life by arranging actual tools sourced from a hardware store. His assistant, Ronnie Cutrone, photographed these arrangements, capturing Warhol’s modern take on the classical still life while keeping with his experimental, production-focused approach to art.

The series speaks to Warhol's fascination with mass media.

Red Lenin (F. & S. II.403) © Andy Warhol 1987

Red Lenin (F. & S. II.403) © Andy Warhol 1987Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle series is a testament to his deep interest in mass media and reproduction. Inspired by graffiti in Italy, where the hammer and sickle symbol appeared repeatedly across urban landscapes, Warhol saw an opportunity to transform this potent political image into a mass-produced artwork. By depicting these tools not as flat symbols but as objects in a still-life arrangement, Warhol added dimension to an icon usually associated with Communist ideology. His process mirrored the industrial reproduction methods he admired, emphasising his belief that even a charged political symbol could be reshaped into consumer-friendly art through mass media techniques.

The series was created from reference photographs.

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.62) © Andy Warhol 1977

Hammer And Sickle (F. & S. II.62) © Andy Warhol 1977For the Hammer and Sickle series, Warhol built on his unique approach of transforming everyday objects into art by using reference photographs. To create this politically charged work, Warhol sourced real tools from a hardware store, arranging them in various still-life compositions. His assistant, Ronnie Cutrone, then photographed these arrangements, providing Warhol with reference images that brought depth and realism to the iconic symbol. By turning these photographs into screen prints, Warhol was able to replicate the compositions, blending his fascination with reproduction with a fresh, dimensional take on a political icon.

The series toys with Soviet iconography.

Image © WikiArt / Beat The Whites With The Red Wedge © El Lissitzky 1919

Image © WikiArt / Beat The Whites With The Red Wedge © El Lissitzky 1919This series playfully reinterprets Soviet iconography, taking a recognisable Communist symbol and reshaping it through the lens of pop art. Rather than presenting the hammer and sickle as rigid, flat symbols of ideology, Warhol rendered them as dynamic, still-life objects, arranged and photographed like ordinary tools, rather than emblems of political doctrine. This approach stripped the icon of some of its revolutionary weight, recasting it as a consumer object available for mass reproduction. By transforming these potent symbols into colorful, commodified prints, Warhol challenged the original meaning behind the hammer and sickle, blending it with his commentary on the nature of symbols, consumerism, and media-driven culture. The series thus merges political and artistic realms, making a playful yet subversive statement about the power—and malleability—of iconic images.

This is is the only published print series to detail the stages of the print making process.

Image © MoMA / Hammer And Sickle © Andy Warhol 1976

Image © MoMA / Hammer And Sickle © Andy Warhol 1976Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle series stands out as the only published collection that reveals the steps involved in his screen-printing process, offering viewers a rare glimpse into his artistic technique. By detailing each stage—from the initial reference photographs to the layering of colors and final touches—Warhol invites the audience to see how an image evolves through various stages of production. This transparent approach demystifies his method, emphasising the labor and repetition inherent in his work, which mirrored industrial manufacturing. By documenting each layer and adjustment, the series reinforces Warhol's commentary on art as a reproducible product.

The series testifies to the universality of imagery.

Image © Phaidon / Hammer And Sickle © Andy Warhol 1976

Image © Phaidon / Hammer And Sickle © Andy Warhol 1976Warhol's Hammer and Sickle series testifies to the universality of imagery by transforming a potent symbol of Soviet power into a broader commentary on iconography, politics, and consumer culture. By isolating the hammer and sickle from their original Soviet context and reproducing them in bright, pop-art colors, Warhol underscores how imagery can transcend its origin to evoke a wide range of meanings and responses. In capitalist America, these symbols had a provocative resonance, conjuring associations with Cold War tensions and the allure of the "other." Yet, Warhol’s treatment of the symbols also strips them of some ideological specificity, rendering them objects of aesthetic fascination and critique rather than purely political statements. Through repetition and vivid colors, Warhol points to the commodification and neutralisation of political imagery, suggesting that any symbol can be appropriated and transformed into a product for mass consumption.