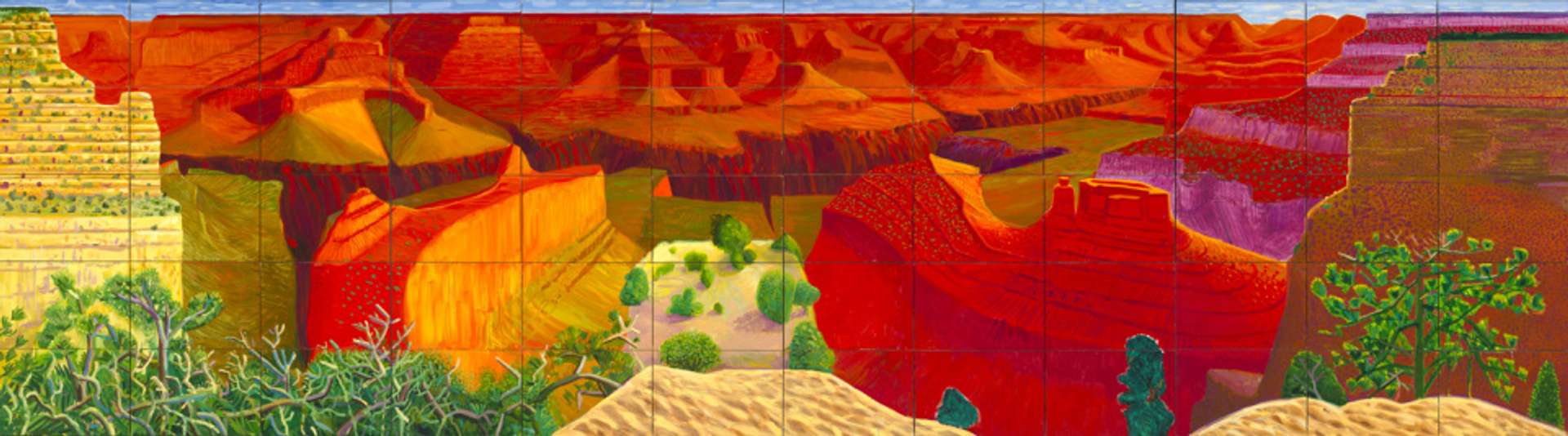

David Hockney's Art Techniques: Technology, Media & Photography

David Hockney: Always Finding New Ways of Looking

When asked in a 1980s interview what made him so popular, David Hockney replied: “I’m interested in ways of looking and trying to think of it in simple ways… Everyone can look. It’s just a question of how hard they’re willing to look, isn’t it?”

He’s never stopped asking how we see – and crucially, how we might see differently. Whether with paintbrushes, Polaroids, fax machines or iPads, Hockney has spent decades exploring new ways of capturing time and space. And long before digital art became the buzzword it is today, he was already treating technology not as a threat to tradition, but as a new medium of translating the world as he sees it.

Hockney has said that he works every single day, so it’s not surprising that he’s always looking for ways to innovate his practice. Since establishing his personal style, he has taken familiar technologies and pushed them to new and novel artistic ends. Around the early 1980s, Hockney invented what he called “joiners,” large-scale photographic collages made by assembling dozens (sometimes hundreds) of separate photos into a single image. These began as Polaroid snapshots and 35mm prints of a scene, which Hockney would manually arrange like a patchwork. Unlike a single photograph, which freezes one moment from one viewpoint, his joiners reveal a scene from multiple perspectives and moments in time - blurring the fine line between still photography and animated film. Hockney believed that this technique was “closer to how the eye actually sees” – not as a single fixed image, but as a succession of glances and changing focus.

In 1986, he began using a photocopier as a literal screenprinter, creating his Home Made Prints. He approached the office machine like a printing press he could create with, discovering that he could layer colours by running images through one-colour toner cartridges repeatedly, swapping colours to build up an image. Suddenly, the printmaking process, once a slow, multi-step process that required technician assistance, became far more spontaneous and solitary. Because of the immediacy of the medium, Hockney said it was the closest he had ever come in printing to what it’s like to paint. It also produced new visual textures in his work thanks to the slightly grainy, halftone effects of the copier, which became part of the overall appeal of the work.

Clearly in this era of fascination with office equipment, Hockney’s interest was even piqued by the fax machine. In the late 80s, fax technology was used mostly to transit business documents over phone lines. In this, Hockney saw a fun opportunity to fax hand-drawn images to his friends. This playful experiment soon led to a bigger idea: why not send art long-distance via phone lines. In 1989, when invited to exhibit at the São Paolo Biennial, Hockney participated remotely by fax. Instead of shipping physical artworks to Brazil, he created faxable compositions over the phone line to be assembled on site. This exercise raises questions both about how artists create their work, but also how they share it with the public.

His real watershed moment in the 21st century was after his adoption of the iPhone and iPad. As soon as the first iPhone came out, Hockney was intrigued by its possibilities. By 2009 he was drawing on the iPhone using the Brushes app, sketching everything from flowers to sunsets with just his finger on the small screen. He turned the iPhone into his digital sketchbook that was more portable and immediate than any traditional media.

When the iPad came out in 2010, he eagerly adopted it and relished in the expanded “canvas” size and greater precision it afforded. He famously said, “sometimes I get so carried away, I wipe my fingers at the end thinking I’ve got paint on them,” showing just how tactile and evocative the experience is for him.

The iPad has borne some of Hockney’s largest bodies of prints, in both scale and number, like his Yosemite Suite and the much-celebrated Arrival of Spring. The Arrival of Spring conveys the rural landscape of Yorkshire transitioning from late winter into spring, across over 50 iPad drawings. Each drawing was created en plein air on the iPad, often one a day, documenting the gradual burst of colour and life as spring unfolded. Like the photocopier and fax machine before, the iPad offered Hockney an opportunity for greater immediacy than ever before. Of course, critics at the time questioned whether or not it was “real art,” a sentiment critics love to fall back on when they’re uncomfortable with the unfamiliar and don’t quite know how to navigate it. But with Hockney, you have to trust the process – he’s always a few steps ahead, and history tends to catch up with him eventually.

A swathe of critical recognition came in 2024 following his collaborative show with London’s Lightroom, Bigger & Closer (not smaller and further away). Rather than displaying his works in the gimmicky way a lot of “immersive” exhibitions do, the show immersed visitors into a multi-sensory journey projected onto the venue’s walls.

There’s no one quite like David Hockney. He doesn’t fit neatly into one genre – he never has and he never will. He’s never tried to shape himself into a preconceived mould. Instead, he breaks it and reshapes it – time and time again – to push art to places it hasn’t been before. Nowhere is that more evident than in his unflinching embrace of technology. And through decades of ceaseless experimentation, he’s expanded not only what art can look like, but how we look at it.