WHAAM! Pop and War in the World of Roy Lichtenstein

Whaam! © Roy Lichtenstein 1963

Whaam! © Roy Lichtenstein 1963

Interested in buying or selling

Roy Lichtenstein?

Roy Lichtenstein

293 works

Roy Lichtenstein’s Whaam!’ one of the all-time best known works of Pop-Art.

This text accompanies the image of an American fighter plane that has just launched a missile into an approaching enemy, and following the missile’s trajectory, our eye is led to the resulting explosion - depicted in full Lichtenstein-pop-glory against a backdrop of blue ben-day dots.

Rendered in any other way, perhaps in a photograph or a figurative painting, this scene would be horrific. The stuff of war flashbacks and conflict news coverage. But by Lichtenstein, we are drawn into the work and its detachment from reality, by the aesthetic suggestion of childhood and by the absurdity of an oversized comic strip hanging in the art gallery.

First exhibited in New York in 1963, Whaam! Is as well-loved today as it was when first created, and is now on permanent display in the Tate Modern, where it has been since 2006. It is the pinnacle of Lichtenstein’s (and fellow Pop-Art titan Andy Warhol’s) fascination with consumerism, media culture, and the boundaries of high and low art. So, why is Whaam! And Lichtenstien’s comic-book composition so important in terms of art history? And why is the artist’s use of such a deceptively simple aesthetic so effective at conveying very real messages of war protest and the consequences of desensitised commercialism?

Lichtenstein as anti-war artist?

Whaam! is lifted from a 1962 panel of the popular DC comic book series All-American Men of War, a fitting inspiration if ever there was one. What we are left questioning by Lichtenstein’s choice of inspiration, however, is whether Whaam! is a criticism of our desensitisation to violence, of the Hollywood romanticisation of warfare, or whether it is more of a celebration of fast-paced action and the ‘Pop-Art’ aesthetic?

Context indicates that Whaam! does indeed bear some evidence of Lichtenstein’s more poignant anti-war beliefs. Created when America was on the precipice of heavy involvement in the Vietnam war, and was overwhelmed by the threat of the ongoing Cold War - anti-conflict sentiment across the country was running high. The comic-book appropriation used here can then be read as a parody of military glory peddled in US propaganda. In many ways, the comic book that shapes the minds of young boys, has the same effect as the propagated reports of military glory that encourage support for conflict. The desensitised depiction of an explosion mimics our emotional detachment from the violence we see on the news so often.

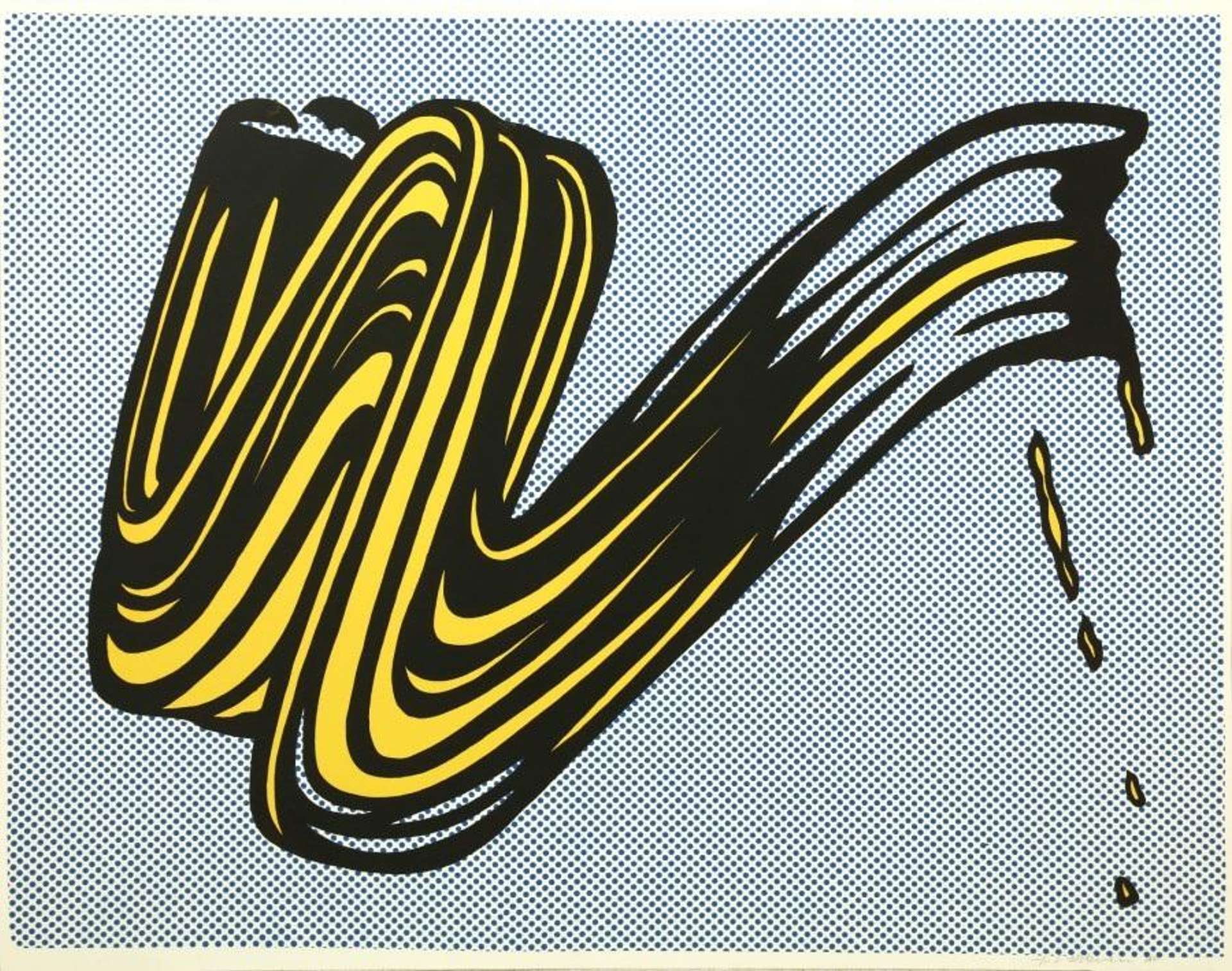

What is important however, is that Lichtenstein maintains that same detachment as an artist in works like Whaam! leaving it up to us to decide what his intentions were. The unresolved duality of violent subject matter and the dispassionate commercial style, leaves the work ultimately unclear. Just look at Explosion, (1965) or Takka Takka, (1962) that embrace the spirit of post-WW2 manufacturing in their visuals, yet convey the very real fears of nuclear annihilation and military drafting that defined the lives of US citizens at the time.

Lichtenstein’s work refuses to spoon feed us, instead creating emotionally charged scenes in such a detached manner, that we are left with no choice but to shovel the meaning of his work in by the handful ourselves.

Takka Takka © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein 1962

Takka Takka © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein 1962Lichtenstein's 'Pop': Personal meets Commercial

Considered one of the fathers of Pop Art, Lichtenstein’s paintings unsurprisingly explore key themes of consumerism and commercial culture, appropriating images from advertisement (and of course comic books) to play with notions of hierarchy in art. It is Lichtenstein’s working methods however, that set him apart from the mass-production screen printing process of Andy Warhol, or the fast paced, site-specific graffiti of an artist like Keith Haring.

Despite the final product being a dispassionate appropriation of popular imagery, suggestive of mass production methods in its clear-cut visuals, Lichtenstein actually rendered paintings like Whaam! painstakingly by hand.

Tate actually holds one of his preliminary pencil sketches for the work, capturing the artist’s process. To create his signature dots, Lichtenstein meticulously pushed oil paint through the holes of a homemade aluminium stencil with a scrubbing brush. So, we now have a work that despite visually assimilating into the commercial form of the genre, maintains a personal artistic signature and traces of Lichtenstein’s own hand.

If the duality of subject matter and aesthetic was not already food for thought, the conflict between visual detachment and the painstaking artistic process behind the comic-book paintings adds a further level of complexity to Lichtenstein’s practice. Rather than simply copying imagery from the commercial world, he creates something new through this unique working process:

Drawing for Whaam! © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein 1963

Drawing for Whaam! © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein 1963Nevertheless, Lichtenstein embraced the realism and evocation of the everyday that characterised Pop Art. In creating large-scale works like Whaam! the artist sought to connect the traditions of high art to the commercial. In tying the ‘commodity’ status of a consumer good, or here a comic, to a work of art, Lichtenstein suggests that art itself, is at the end of the day, a commodifiable product like everything else.

Lichtenstein’s enduring legacy as a cornerstone of the Pop Art movement is being celebrated in 2023, marking the 100th anniversary of his birth. His centennial has sparked global recognition, including major exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Rose Art Museum, and the Albertina. In honor of this milestone, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation is donating 186 of his works to five major institutions, ensuring his innovative exploration of the relationship between art and consumer culture continues to inspire future generations.