Problematic Picasso

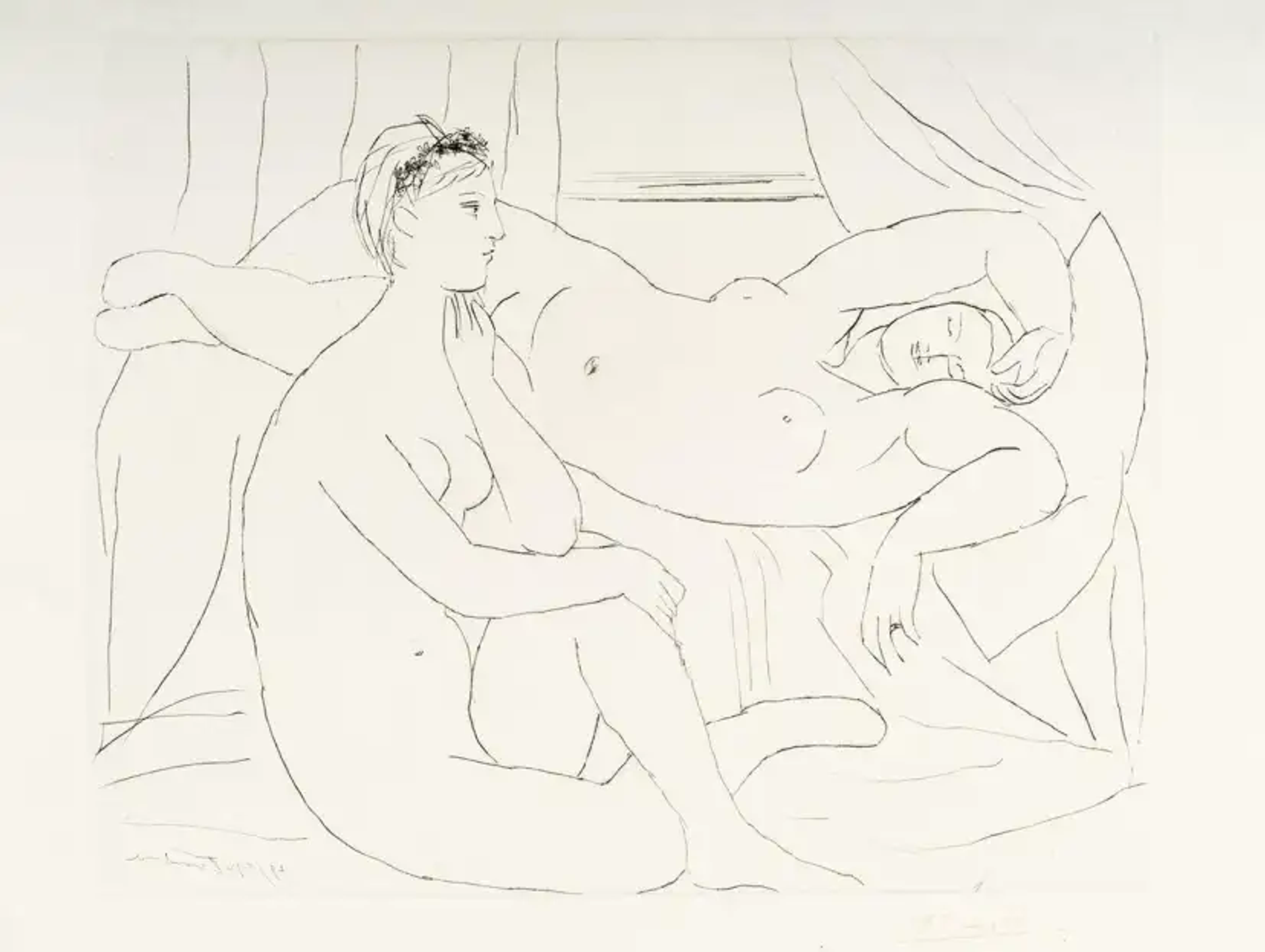

Femme Endormie © Pablo Picasso 1962

Femme Endormie © Pablo Picasso 1962

Pablo Picasso

160 works

Key Takeaways

Pablo Picasso's artistic brilliance is undeniable, yet his legacy is shadowed by deeply problematic aspects of both his personal life and creative process. His relationships with women were marked by manipulation and control, and his appropriation of non-Western art, particularly African influences, raises critical questions about cultural exploitation. As we reassess Picasso’s impact, we are called to reconcile his revolutionary contributions to modern art with the ethical complexities that challenge our understanding of his enduring influence.

Pablo Picasso is often celebrated for his groundbreaking contributions to Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism. However, in recent decades, Picasso’s personal life and artistic practices have come under intense scrutiny. Today, we confront Picasso as both a revolutionary artist and a deeply problematic figure whose complex legacy must be reevaluated within the context of his misogyny and cultural appropriation. Contemporary criticism highlights his behaviour toward women and his appropriation of non-Western art, while posing the question of whether we can separate the art from the artist.

Picasso’s Misogyny: Women as Muses, Objects, and Victims

Picasso’s relationships with women were as much a part of his legacy as his art, and they were marked by an unsettling pattern of power, possession, and emotional domination. Throughout his life, Picasso was romantically involved with a series of women, many of whom were significantly younger. These women, including Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, and Marie-Thérèse Walter, were not merely sources of artistic inspiration; they were subjected to emotional manipulation, cruelty, and objectification. Picasso’s famously sexist declaration, “There are only two kinds of women; goddesses and doormats”, reveals much about the stark binaries he imposed on the women in his life. To him, they were either deified and idealised, or diminished and degraded, with little room for complexity or autonomy. This reduction of women to archetypes, either divine or debased, stripped them of their humanity and agency. In this binary worldview, Picasso could revere a woman one moment and discard her in the next, a dynamic that played out both in his personal relationships and in his art.

Women in Picasso’s Art: Beauty or Brutality?

Picasso’s complex relationship with women is reflected not only in his personal life but also in his artistic output, where his portrayals oscillate between reverence and violence, beauty and brutality. His depictions of women are often fragmented and distorted, evoking a duality of admiration and destruction that speaks to the underlying tensions in his relationships with them. This tension is perhaps most famously displayed in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a revolutionary work that shattered traditional perspectives in art, yet also embodies a disturbing undercurrent. The women in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are depicted with distorted, disjointed bodies, their forms reduced to sharp, jagged planes that seem to deny their humanity. This stylistic choice is undeniably part of Picasso's cubist experimentation, but it also evokes a sense of violence. The angularity and fragmentation of their bodies disrupt the soft, flowing curves traditionally associated with female figures in Western art, instead rendering them almost grotesque, more like objects than subjects. While this piece is celebrated for its bold departure from classical forms, it also raises unsettling questions about Picasso’s view of women.

The women in Picasso’s art are frequently reduced to mere objects or abstract forms, their bodies twisted, fragmented, or fused with inanimate elements like furniture. For example, in works such as Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, Picasso intertwines his lover Walter’s body with the furniture around her, reducing her to a decorative, almost inanimate, object. This technique not only demonstrates Picasso’s mastery of form and abstraction, but also speaks to a deeper, more troubling view of women. They become malleable, fragmented, and dehumanised, transformed into objects of aesthetic experimentation rather than fully realised individuals.

Picasso's artistic experimentation with form, composition, and perspective is undeniable, and his work is rightly celebrated for its innovation. However, beneath the surface lies a darker narrative; Picasso’s exploration of women reminding us that his creative genius was deeply intertwined with a damaging view of the feminine. In this sense, Picasso’s art cannot be disentangled from the complexities of his relationships with women, where admiration was so often shadowed by violence and objectification.

Exoticism and “Primitive” Cultures: Picasso’s Appropriation of African and Iberian Art

Picasso and African Art: Inspiration or Exploitation?

Picasso’s artistic practice was deeply shaped by non-Western art, particularly African and Iberian influences. His fascination with these cultures is evident in some of his most iconic works, notably Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, where two figures are modelled after African masks. These elements marked a radical departure from the classical Western traditions that dominated European art at the time. Picasso’s exposure to African masks and sculptures in Parisian museums offered him an alternative to Western perspectives on form, anatomy, and representation. However, while these influences were pivotal in the development of modern art, Picasso's use of non-Western forms is not without ethical and cultural implications. His engagement with African and Iberian art, like many of his contemporaries, was fundamentally extractive and often problematic.

Picasso’s appropriation of these forms was part of a broader movement among European artists of the early 20th century, who viewed non-Western art through an exoticising and reductive lens. Rather than recognising the deep cultural, religious, and social significance embedded in African and Indigenous artistic traditions, Picasso, among others, treated these forms as visual material for their own aesthetic experimentation. African masks, in particular, were seen as symbols of the “primitive,” an idea rooted in colonial attitudes that positioned non-Western cultures as underdeveloped, but aesthetically intriguing. For Picasso, these masks represented a way to break the mould of traditional European figuration, allowing him to fragment and distort the human form in ways that were revolutionary in the context of modern Western art. Yet, in doing so, he disregarded the original cultural and spiritual meanings of these objects, using them purely for visual innovation without crediting or respecting the people and traditions from which they came.

Colonialism and Picasso’s Impact on Modern Art

This practice of borrowing non-Western art forms without acknowledgment of their original contexts was not unique to Picasso. It reflects a broader colonialist mindset that dominated European thinking during the period. Artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Derain were influenced by the influx of non-Western art into Europe, particularly as colonial powers looted, displayed, and sold African and Indigenous artefacts. These pieces were often stripped of their cultural significance and recontextualised as “primitive” artefacts, useful for disrupting European conventions but not seen as part of a sophisticated or equal artistic tradition. This reduction of non-Western art to mere aesthetic inspiration perpetuated the dehumanisation of colonised peoples.

Unlike Paul Gauguin, who spent significant time living in Tahiti, Picasso never directly engaged with African or Indigenous cultures. Gauguin's time in Tahiti, while problematic in its own right due to his romanticisation of Polynesian life and his personal exploitation of Indigenous women, at least involved a degree of immersion in the culture. Picasso, however, encountered African art within the context of European colonial displays, primarily in Parisian museums. His fascination with these objects was intellectual and artistic rather than cultural or spiritual, reflecting a more detached and commodifying view of non-Western art. This lack of direct engagement with the cultures from which he drew inspiration reinforces the exploitative nature of his appropriation.

The broader art world has since grappled with the implications of Picasso's appropriation of non-Western art. The Ugandan artist Francis Nnagenda's reflection; “People tell me my work looks like Picasso, but they have it wrong. It is Picasso who looks like me, like Africa”, powerfully underscores the reverse influence that was never acknowledged by Picasso or his contemporaries. Nnaggenda’s statement speaks to the ongoing legacy of this appropriation and raises important questions about the ethics of borrowing from marginalised cultures without recognition or understanding. Picasso’s revolutionary breakthroughs in form and perspective came, in part, at the expense of the cultures he appropriated, and this dynamic remains a critical point of reflection in modern discussions about colonialism and the history of art.

A Product of His Time or Willful Ignorance?

In the context of the #MeToo movement and a growing cultural focus on accountability, Picasso's legacy is undergoing a re-assessment. Half a century after his death, his status as an artistic titan is being challenged by a re-evaluation of his personal behaviour, especially his treatment of women. Exhibitions like It’s Pablo-matic at the Brooklyn Museum, curated by comedian Hannah Gadsby, exemplify this shift. Gadsby's feminist critique of Picasso offers a lens through which to reexamine his legacy, grappling with the tension between recognising his undeniable artistic brilliance and condemning his troubling behaviour. The exhibition, while acknowledging his groundbreaking contributions to art, also seeks to confront the misogyny that was pervasive in both his personal life and creative process.

The cultural shift brought about by the #MeToo movement has enabled a larger conversation that calls for a reconciliation between artistic achievements and personal ethics. Picasso's treatment of women is not an isolated flaw but a reflection of the systemic misogyny that exists within the art world, where male artists have been given licence to behave reprehensibly, often under the guise of creative genius. The romanticised myth of the male artist, tormented, passionate, and above conventional morality, has historically allowed for the erasure of the suffering experienced by the women in their orbit. This mythology, once viewed as part of the price paid for great art, is being dismantled as feminist critics and scholars call for accountability.

However, the reevaluation of Picasso's legacy is not solely focused on his personal life. His exploitation of non-Western cultures also raises ethical questions about the intersections of art, colonialism, and cultural appropriation. Picasso’s groundbreaking use of African and Iberian art in works like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was transformative for Western art, yet it was also deeply problematic in its disregard for the cultural significance of the art forms he borrowed from. By reducing African masks and sculptures to mere aesthetic tools for his own innovation, Picasso engaged in a form of cultural appropriation that dehumanised the very cultures he drew inspiration from. This exploitative dynamic is part of a broader history of Western colonialism, where non-Western art and artefacts were taken out of their original contexts, often looted or purchased under unequal conditions, and displayed in European museums. Picasso's failure to engage with the deeper meanings behind the forms he appropriated reflects a colonial mindset that continues to resonate in modern discussions of cultural ethics in art.

Can We Separate the Art from the Artist?

The feminist critique of Picasso is not an attempt to erase his work or diminish its significance, but rather to engage in a more nuanced and honest conversation about the context of his art. It calls for a re-evaluation that includes the voices and experiences of those who have historically been silenced or marginalised in the telling of his story. Picasso’s art reshaped the boundaries of modernism, but his legacy is also marked by a pattern of exploitation that demands reflection. Philosopher Berys Gaut’s observation that an artist's moral character can shape the content of their work is particularly pertinent in Picasso’s case. His misogyny and objectification of women are not merely abstract accusations; they manifest in his art, where women are frequently portrayed as fragmented, distorted, and dehumanised. These depictions are inseparable from the reality of how Picasso treated the women in his life, revealing a troubling intersection between personal ethics and artistic output.

In the 21st century, we are learning that it is possible to celebrate artistic achievement while also condemning unethical behaviour. Picasso’s legacy is multifaceted; his contributions to modern art are undeniable, yet the cost of those contributions cannot be ignored. The re-examination of Picasso is not just about one man; it is about how we reconcile transformative art with the personalities that created it. The answer, as suggested by exhibitions like It’s Pablo-matic, lies in embracing complexity rather than seeking easy resolutions. We must acknowledge that Picasso’s work exists within a broader context of exploitation, and by critically engaging with these uncomfortable truths, we can create a more nuanced and responsible conversation around art and ethics. As we continue to engage with Picasso’s work, we are also engaging with the broader cultural shift toward accountability, responsibility, and the demand for a more ethical art world.

Moving Forward: Addressing Problematic Artists

In the ongoing discussion of Picasso's legacy, we are called to confront the tension between his artistic brilliance and his personal transgressions. His groundbreaking contributions to modern art, particularly his role in the development of Cubism and the avant-garde, cannot be denied. Picasso revolutionised the way we see form, perspective, and abstraction, and his work remains foundational to the history of 20th-century art. Yet, his treatment of women and his appropriation of non-Western cultures remind us that even the most celebrated figures can be deeply flawed, and these flaws are not external to their art but intertwined with it. Current cultural moments, shaped by #MeToo and a heightened awareness of historical injustices, demands a more critical engagement with figures like Picasso. This does not mean erasing his contributions or cancelling his work. Rather, it calls for a more nuanced conversation that acknowledges the complexity of his genius while also holding him accountable for the harm he caused. In doing so, we open the door to a future where artistic achievement is celebrated, but not at the expense of the people and cultures that artists exploit or harm.