Andy Warhol's Death & Disaster Series

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.81) © Andy Warhol 1971

Electric Chair (F. & S. II.81) © Andy Warhol 1971

Interested in buying or selling

Andy Warhol?

Andy Warhol

493 works

Many people associate Andy Warhol's art with lighthearted themes and motifs, especially his portraits of stars and Campbell's Soup cans. Less widely known yet equally significant in Warhol's oeuvre is his Death and Disaster series, a loosely bound group of around 70 artworks created between 1962 and 1967. Here, the artist often associated with celebrating the superficial side of Pop culture turns his gaze to the role the media plays in commodifying and glorifying death and tragedy. A more introspective series, it carries the hallmarks of Warhol's art: repetition, contrast and colour, to highlight an obsession with violence and disaster.

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Photograph of the American artist Andy Warhol in Moderna Museet, Stockholm 1968

Image © Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons / Photograph of the American artist Andy Warhol in Moderna Museet, Stockholm 1968The Origins of Death & Disaster

Warhol first achieved success as a commercial fashion illustrator, famously for a shoe brand. During this period he frequently drew and painted using his blotted line technique, something that culminated in A La Recherche du Shoe Perdu, completed in 1955. By the end of that decade, he aspired for recognition as a fine artist. To break into this scene, he looked for subject matter that could set him apart.

In the early 1960s, he started to experiment with paintings based on mass-produced images from popular culture, including comic strips, advertisements and product labels. The first instance of Warhol's use of screenprinting as a fine art technique is generally considered to be around 1962. He recognised the potential of the process to create art that emphasised and celebrated the mass production and consumerism dominating post-war America, and also allowed him to produce artworks more rapidly and in larger quantities.

Soon thereafter he began sourcing images from print and newspapers to create his artworks, and the Death & Disaster Series stems from this development. Originally titled Death in America, the series was first created for Warhol’s major European debut at Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery in Paris in 1963.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / 5 Deaths © Andy Warhol 1963

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / 5 Deaths © Andy Warhol 1963Death & Disasters as an Allegory: The Meaning Behind the Works

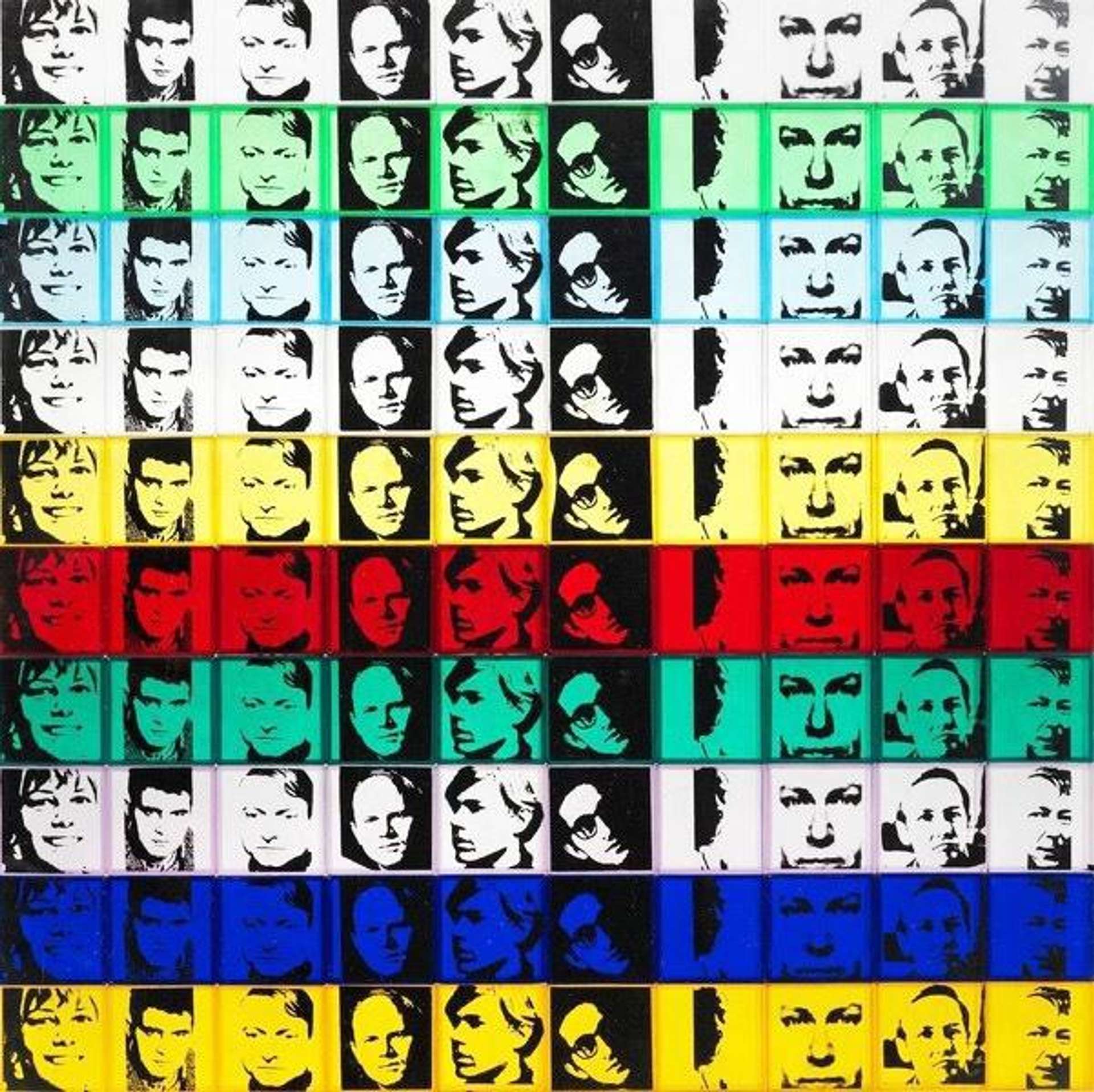

As with much of Warhol's work, repetition is a major feature: the same image is often repeated multiple times in a single piece, mirroring the omnipresence of such imagery in the media and having a desensitising effect on the viewer. He also often employed bright, incongruous colours in these works, contrasting the grim subject matter with his pop sensibility.

The series can be seen as a commentary on the way the media presents and consumes tragedy. Warhol seemed to be making a statement about the detached and mechanical way in which society encounters and processes these horrific events. By presenting them in a repeated and almost commercial format, he raises questions about desensitisation of the public and the nature of celebrity. Furthermore, the subject matter encapsulates the apocalyptic fears of the Cold War generation in the United States.

Some scholars also consider the Death & Disaster series to be a 20th century version of the Danse Macabre, a late Mediaeval and Early Modern allegory that reminds viewers of the inevitability of death in order to foster a sense of urgency for the repentance of sin. This is a brilliant assessment, especially when one considers Warhol's profoundly Catholic upbringing.

Image © X @jonaquest / 129 Die In Jet! installation view

Image © X @jonaquest / 129 Die In Jet! installation view129 Die In Jet! (1962)

The painting 129 Die In Jet! was, by Warhol's own admission, his first foray into the subject of death. In an interview with Artnews in 1963, Warhol said he began exploring death with “the big plane crash picture, the front page of the newspaper: 129 Die. I was also painting the Marilyns. I realised that everything I was doing must have been Death. It was Christmas or Labor Day—a holiday—and every time you turned on the radio they said something like '4 million are going to die.' That started it.”

The work replicates a front page showing the aftermath of the accident involving Air France Flight 007, in which 129 people had died (at the time of the headline, at least). Interestingly, a significant portion of the victims were art patrons heading home from a month-long tour of the art treasures of Europe organised by the Atlanta Art Association. Maybe it was this association with the art world that first pushed Warhol to explore the subject in this new medium.

Suicides (1962-63)

Soon thereafter, Warhol made a painting of the so-called "most beautiful suicide", that of Evelyn McHale, who jumped to her death from the Empire State Building in 1947. A photography student took a picture of her body immediately after the incident, and the image entered pop consciousness at large. Warhol sourced the image from Life Magazine in order to create Suicide (Fallen Body) in 1962, and repeated the image dozens of times with varying degrees of clarity.

He returned to the subject for Suicide (Jumping Man) in 1963, creating the work in purple and silver. The purple version was purchased by Tony Shafrazi, who gave it to the collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in Iran, where it remains to this day.

Image © Christie's / Tunafish Disaster © Andy Warhol 1963

Image © Christie's / Tunafish Disaster © Andy Warhol 1963Tunafish Disaster (1963)

This was one of Warhol's smaller disaster series. For this work, he used a page from Newsweek dated April 1, 1963, featuring a story about a can of contaminated tuna that killed two housewives in suburban Detroit, Michigan. The victims' Americana appearance appealed to Warhol, who created a group of eleven paintings based on the incident. The artist repeated the image of the tuna can with its cut-off caption several times against a silver background. It is the only one within the series that was created exclusively in a single colour.

Electric Chair (1963)

One of the most famous iterations of the Death & Disaster series is the group of images depicting an electric chair. This collection of artworks delves into mortality, media sensationalism and the more haunting facets of contemporary life. Centred around an arresting image of an empty electric chair in a desolate room – a photograph sourced from Sing Sing prison in New York – Warhol employs bright and almost garish colours, juxtaposing them against the sombre subject. This colour choice forces viewers into a contemplative space, confronting the sensationalisation and normalisation of capital punishment in the media and American culture at large. The series serves as a profound societal commentary, with the electric chair standing as a chilling symbol of state-sanctioned execution, questioning the ethics of the death penalty, the media's role in shaping our views on justice and the intersection of institutional authority and individual mortality. Furthermore, Warhol's use of screenprinting, a method allowing for a degree of detachment, resonates poignantly with the series' theme, mirroring the cold, mechanised nature of capital punishment.

Image © Sotheby's / White Disaster © Andy Warhol 1963

Image © Sotheby's / White Disaster © Andy Warhol 1963Car Crashes (1963)

One of the most prolific motifs within the Death & Disaster series is that of car crashes: Warhol created over a dozen of these. These pieces delve into the haunting intersection of personal tragedy and mass media, using images from tabloid newspapers and police archives to encapsulate the raw horror of real-life accidents. His fascination with the commodification of such intimate, distressing events in a media-saturated society is most palpable in these works: identical images of mangled vehicles and distress are endlessly multiplied across the canvas, echoing the relentless broadcasting of trauma in American culture.

In the context of 1960s America, marked by its rapid urban evolution, societal upheavals, and burgeoning automobile culture, Warhol's car crash paintings resonate profoundly. They compel viewers to confront the precarious balance of progress and vulnerability, challenging our perceptions of speed, innovation, and the often-blurred lines between media sensationalism and genuine tragedy.

Jackie Kennedy (1964)

Warhol's Jackie series, produced following President Kennedy's assassination in 1963, offers a poignant portrayal of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in both joyous and sombre moments. Drawing from newspapers and magazines, Warhol captured Jackie's signature elegance juxtaposed with her palpable grief. The series poetically encapsulates the transition from the Camelot era's allure to the reality of a nation in mourning.

In this specific series, repetition is even more crucial: the technique amplified the relentless media attention on the First Lady, commenting on the nature of fame in times of public crisis. Through repeated images with subtle variations in colour and detail, Warhol creates a series of visual echoes, mirroring how such profound moments linger in collective memory. Warhol's Jackie series stands out for its emotional depth; here, Jackie's face becomes a canvas for both personal anguish and a country's shared heartbreak, positioning her as an enduring icon of grace amid adversity.

The Contemporary Relevance of Warhol's Death & Disaster

The Death & Disaster series offers a poignant and provocative exploration of the relationship between media, mortality and the human psyche. Its haunting images and bold aesthetic choices ensure its place as one of the most memorable and discussed aspects of Warhol's body of work, and one that is increasingly relevant today, with the ubiquity of smartphones and social media. Warhol's exploration into the voyeuristic consumption of calamity is relevant to today's digital age, where the immediate instinct is to photograph and share any event – however tragic – on social platforms. Scenes of accidents, violence, or other distressing incidents are often captured and disseminated within minutes. This rampant documentation, largely facilitated by smartphones, mirrors Warhol's repetitive portrayal of tragic images, echoing his commentary on overexposure leading to desensitisation.

In contemporary society, the ease with which images are shared on platforms like Twitter, Instagram and Facebook has muddied the waters of empathy and privacy, as the line between concern and morbid curiosity becomes blurred. Just as Warhol's series underscored the media's role in the commodification of tragedy during his time, the current digital landscape reveals an intensified version of this phenomenon, where personal misfortunes can virally spread, becoming both spectacle and entertainment.

Warhol's Death & Disaster series offers a prescient critique of a society's detachment from the realities of suffering. It raises questions about our responsibilities as consumers of media and as witnesses to tragedy, issues that are all the more pressing in an era where every individual has the power to amplify distressing events to a global audience. The series serves as a stark reminder of the need for sensitivity, discretion and genuine empathy in a world overflowing with easily accessible yet jarring visual information.