Art Under Siege: The Politics Behind Defacing Masterpieces

Image © FMT / Soup Thrown At Van Gogh’s Sunflowers © 2022

Image © FMT / Soup Thrown At Van Gogh’s Sunflowers © 2022Market Reports

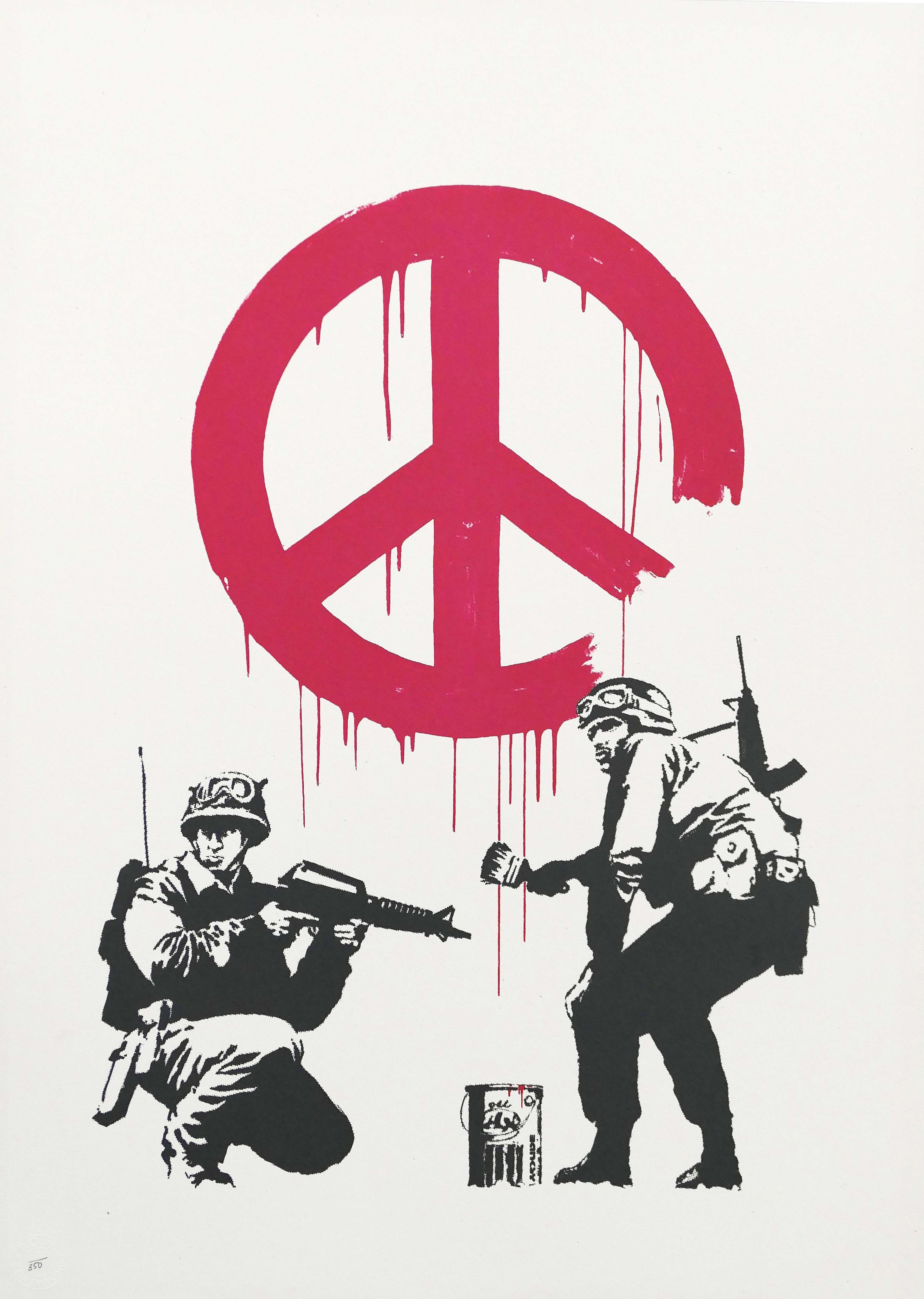

Throughout history, art has served as an enduring testament to beauty, power, and the prevailing values of its time. But in moments of upheaval, it has also become a battleground. From the suffragette Mary Richardson’s infamous slashing of Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus in 1914 to Tony Shafrazi’s graffiti protest on Picasso’s Guernica in response to the My Lai massacre, artworks have frequently borne the brunt of political anger. In the present day, as the climate emergency escalates and public trust in political institutions evaporates, this tradition of iconoclastic protest has been revived.

However, Just Stop Oil, arguably the most visible face of contemporary art-based protest, has recently announced it is ceasing its disruptive tactics. After three years of high-profile interventions, the group has declared a final action is planned in London’s Parliament Square on 26 April, after which the group will no longer operate under its current banner. The decision comes as the UK government formally adopts Just Stop Oil’s original demand to end new oil and gas licences.

A Legacy of Iconoclasm

The politicised destruction of images is no novelty. During the Protestant Reformation, iconoclasts obliterated religious art to condemn the opulence and perceived idolatry of the Church. Centuries later, suffragette Mary Richardson took a butcher’s knife to Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus in 1914, declaring her a contradiction to the reality of women’s disenfranchisement. Her act crystalised the notion that art can be weaponised to dramatise injustice. In 1974, when Tony Shafrazi daubed red paint on Picasso’s Guernica in protest at the My Lai massacre, his target was not the painting, but the violence it represented, and as a response to the atrocities committed in Vietnam.

The Mechanics of Modern Spectacle

Today’s climate activists consciously draw upon this lineage, most visibly through the actions of Just Stop Oil. Founded in 2022, the group has used art institutions as platforms for some of its most controversial interventions. One of their most scrutinised acts of art defacement took place on 14 October 2022, when two activists hurled soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers at the National Gallery, before glueing themselves to the wall beneath the painting. Though the work was protected by glass and unharmed, the incident quickly made headlines across global news and social media. Similar actions throughout 2022 included activists targeting Constable’s The Hay Wain at the National Gallery, Turner’s Thomson’s Aeolian Harp in Manchester, and Van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom at the Courtauld Gallery. Protesters even shattered the glass protecting Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus using safety hammers in a choreographed attack designed to avoid harming the painting itself.

For Just Stop Oil, spectacle is the point, designed to attack public indifference and media fatigue. The effectiveness of these protests lies in their visibility. Just Stop Oil seeks an emotive response that forces the climate crisis back into the cultural and political mainstream. For those involved, the stakes justify the tactics, seeing their interventions not as acts of desecration, but as desperate acts of preservation.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Sunflower © Van Gogh 1889

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Sunflower © Van Gogh 1889 Why Art?

Art institutions have long presented themselves as apolitical spaces dedicated to the preservation and celebration of culture. Yet in reality, museums and galleries are embedded within wider networks of financial, political and ideological influence. Many of the UK’s leading art institutions, including the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, have historically received sponsorship from oil and gas companies such as BP and Shell. Though BP ended its partnerships with several major UK cultural institutions between 2016 and 2023, the legacy of fossil fuel patronage persists, not only in funding records but in public perception. These relationships have drawn sustained criticism from environmental groups, artists, and academics, who argue that such sponsorships amount to a form of “greenwashing”; allowing extractive industries to launder their reputations through associations with “high” culture. Activists seek to draw attention to this underlying infrastructure. By targeting highly visible and symbolically loaded works, activists force the public and the media to confront uncomfortable connections between cultural conservation and environmental destruction. Proponents argue that radical intervention is the only way to rupture widespread apathy.

Critics, however, point to research indicating that extreme disruption may harden opposition. Climatologist Michael E. Mann’s 2022 study suggests that aggressive tactics can alienate moderate observers, reinforcing perceptions of activists as extremists. Historical analyses of social movements echo this ambivalence: while dramatic demonstrations galvanise supporters, they can simultaneously repel the undecided. To date, the evidence that art defacement reliably produces positive outcomes remains inconclusive.

Alternative Campaigns

While sensationalist forms of art activism can effectively spotlight misplaced societal priorities and provoke powerful emotional reactions, they also risk radicalising movements to the point of alienation from mainstream support. By contrast, there is strong evidence that non-destructive, art-centric protest can deliver lasting impact. Between 2007 and 2016, artists and activists targeted BP’s sponsorship of the Tate galleries through a series of imaginative interventions. Without vandalism, they staged performance‑art spectacles in museum foyers, circulated open letters signed by hundreds of creatives and marshalled petitions that captured public imagination. The cumulative pressure convinced BP to sever its ties with the Tate, marking a landmark victory for art‑based advocacy. Similarly, photographer Nan Goldin’s crusade against Sackler family funding of major museums combined exhibitions, public talks and strategic dialogue with trustees. By documenting the connection between arts philanthropy and the opioid crisis, Goldin compelled institutions such as the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to remove the Sackler name from their galleries. These campaigns demonstrate that when activists target institutions with sustained pressure, they can secure reform without sensational spectacle.

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Just Stop Oil Walking Up Whitehall © 2023

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Just Stop Oil Walking Up Whitehall © 2023 Climate activists continue to redefine the role of art as a catalyst for transformation. Art defacement inevitably provokes and disrupts, but as spectacle increases, meaning can dissipate. For art activism to move beyond outrage, it must bridge the gap between symbolism and substance. While targeting art undoubtedly ignites debate, history shows that the most effective campaigns are those that maintain pressure over time, engage a broader public, and hold institutions to account.