Why We're So Hooked on 250 Years of Art Market Tradition

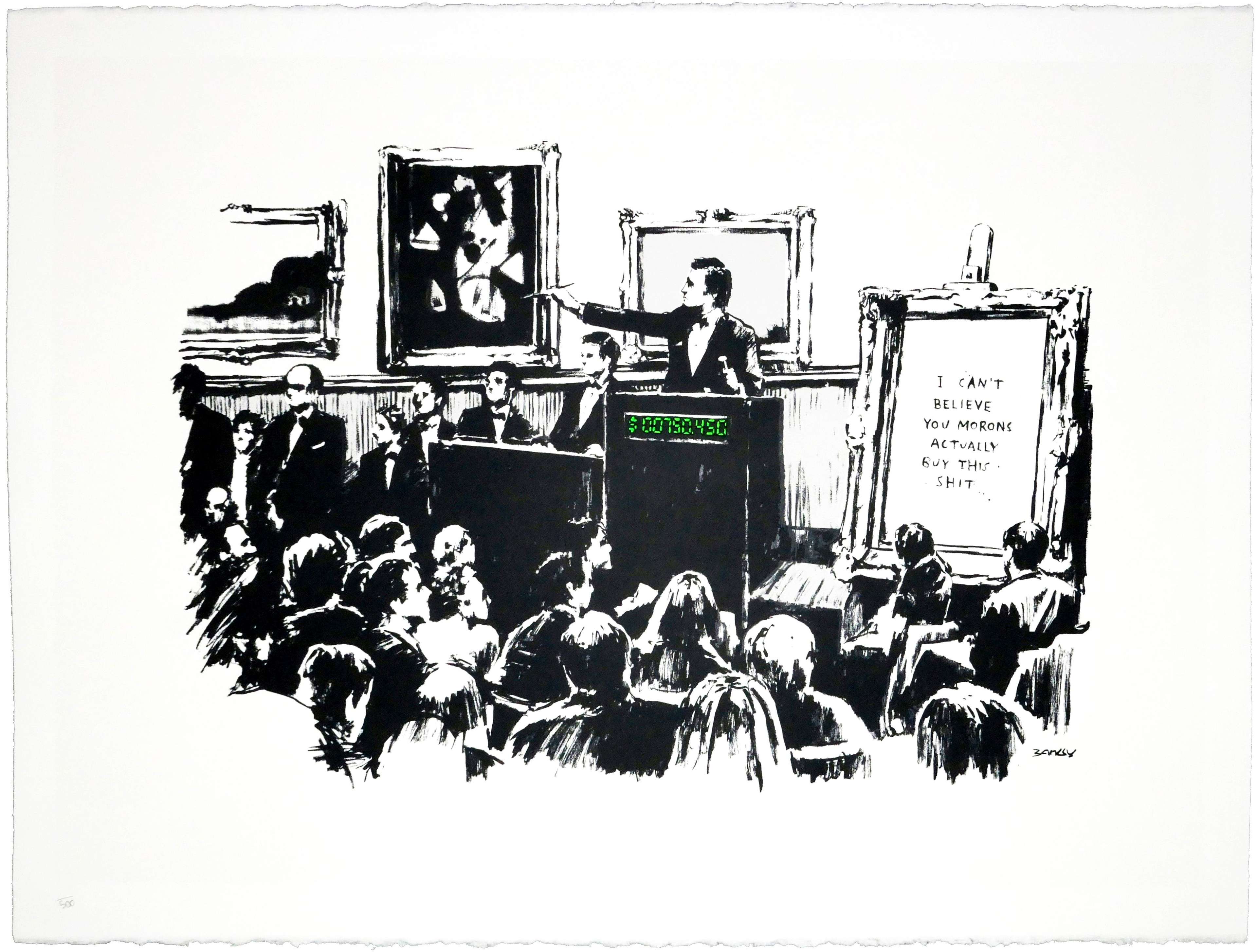

Morons © Banksy 2007

Morons © Banksy 2007Market Reports

Charlotte Stewart questions the persistent appeal of tradition in the buying and selling of art, examining why the industry clings to age-old practices at great cost to collectors, the trade and the planet.

The 1960s is often cited as the decade ‘art as an asset’ took root, flourishing into today's thriving estimated £70 billion art market, while acknowledging the millennia of art commerce preceding this era, it is only when there is considerable money to be made, there is any real need or desire for industry and expansion.

I recently bought a first edition critical Pop Art theory book from 1968 for a friend, flicking through the pages you come across the then not-so-household-name of Andy Warhol, and the more established Jasper Johns. Basquiat and Haring haven’t yet really ‘arrived’ on the scene. What’s striking is the relative newness of this billion-dollar market, contrasting with the ancient backdrop it still operates within. The book is a testament to its time, attempting to define emerging artists without foresight into their future market standing just 50 years later.

As I write I am acutely aware of the current art economic climate post-COVID, post-NFT boom, post-crypto and post-what's-next? I will try not to be like the author of that book in the following, but of course, I can’t not be.

Portrait of Juan de Pareja by Diego Velázquez, c. 1650

Portrait of Juan de Pareja by Diego Velázquez, c. 1650The first artwork ever to sell for over £1m

When that book went into publication, something else was happening in the art market: Christie’s auction house broke the record for the first artwork to sell for over a million pounds. It was, of course, Velázquez’s portrait of his assistant Juan de Pareja, and it sold for £2.3m, nearly tripling it’s pre sale estimate. In the week leading up to the auction the international press - who are in part to thank for the market’s swift development in the past 50 years - became very excited by the possibility that the sale might beat the previous record of £821,482, realised 10 years earlier.

Now try to imagine believing that Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days, a digital artwork, could reach US$69.3 million just 50 years later. (From my perspective that’s way more significant than Salvator Mundi realising £450 million in 2017.)

That Velázquez's portrait sale in 1970, compounded with the general growth of technology in the last four decades which gave birth to an international economy and finance converged, and catalysed the transformation of art into a lightning-speed financial asset economy.

Image © Heni / The Beautiful Paintings © Damien Hirst 2023

Image © Heni / The Beautiful Paintings © Damien Hirst 2023Art & Money

The dynamic relationship between art and money, dating back centuries, has evolved faster than we can keep up with, into a complex market where prices become proxies for preferences, offering insights into both financial portfolios and profound aesthetic debates.

Jumping back some time well before 1972 and the sale of Velázquez's portrait: the art market, as we know it today, has roots that trace back at least two hundred and fifty years, coinciding with the Industrial Revolution. Auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's, established in the 18th century, continue to dominate the secondary art market, a vital facet of the broader financial market.

Art & Tech in 2024

Here's the clincher: Despite the evolution of technology and the emergence of new opportunities in the marketplace, these antique auction giants maintain their traditional structures, and considerable market sway, and some collectors are still paying exorbitant premiums to transact with them.

Despite the distinct segments within the art market—ranging from sculptures to paintings, photographs, antiques, video installations, NFTs —the market remains characterised by low liquidity, high transaction costs, opacity, and conflicts of interest.

Selection Bias in Market Data

Whilst as discussed the art market has made considerable progress, it is dwarfed in size by more established financial markets, yet it commands an outsized share of attention due to its unique cast of high profile characters, press worthy sales, and the enduring impact of art on human culture.

While some traditionalists in the art world may express scepticism about quantitative techniques of pricing, the marriage of financial tools and empirical evidence derived from art prices opens new vistas of understanding especially in a world where public auction records, at first glance, seem to be the only way of drawing parallels and comparables to decipher value.

The stock market or real estate has indicators based on traded stocks or sold houses, challenging the notion of selection bias in art auction data. It’s simply harder to apply those statistical and modelling techniques onto the art market - though in the print market, and luxury market - where editions and series are an inherent part of the asset - there is so much more scope.

Last Friday I spoke with the founder of an innovative tech disruptor in the art market, Convelio founder Edouard Gouin. Convelio is a fascinating company designing a system fit for the 21st century, and we discussed the challenges we both face. One of those is that whatever part of the market you've built technology in, you are in essence asking a product to do something that has been done for hundreds of years by a human with complex and deep expertise. To simply put it: Can Convelio replicate the knowledge of an auction Logistics Manager with 20+ years of experience in a single product? Can we at MyArtBroker replicate the knowledge of an art dealer who has been trading Hockney prints and originals to the most concentrated network of dealers and private clients since the inception of Hockney’s early works into a single product?

Whether you think we can or not is kind of only really critical for us, but the industry itself needs to shift.

Otherwise we may as well all be living in 1970, crowded round Steve Wozniak’s computer in his garage in Los Altos, live streaming the Velázquez's portrait hammering at £2.3million at Christie's.

So why is it that this thriving economy so many of us call home is, in the most part, still not fit for the 21st century?

I love auction houses for the drama, they are excellent theatres, but are they really good businesses? The theatre analogy is a good one. They require international bricks and mortar locations where a large group of people can collect, they throw mass shows that go on tour at great expense to themselves and the environment, in all the major cities. They specialise in nothing completely but everything at once, from miniature snuff bottles to contemporary paintings. They offer their clientele anything they want, as long as they can source it in time for a single moment high-end bring-and-buy sale, where the vendor and the buyer give away a substantial chunk of the profits.

So here we are in 2024, and as we at MyArtBroker enter a year of discovery with our product, and a new series on MyArtBrokerTalks celebrating tech innovators in this ancient art market landscape, I salute the dynamic entrepreneurs, out of the box thinkers, disruptors that challenge the status quo of this antiquated industry. The artists we buy and sell bring us innovation, daring to think differently, re-inventing the new - more of us should step up into the ever-evolving landscape of the art market and take their lead.