Setting the Stage: Pablo Picasso's Foray Into Ballet

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Detail of Picasso’s stage curtain design for Parade 1917

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Detail of Picasso’s stage curtain design for Parade 1917

Pablo Picasso

160 works

Pablo Picasso, a name synonymous with groundbreaking art and modernism, was not only a master of the canvas but also an influential figure in the realm of ballet. His lesser-known yet significant contributions to the performing arts, where his vibrant creativity and avant-garde vision found a new stage, are a testament to his versatile genius. From designing mesmerising backdrops and costumes to collaborating with prominent composers and choreographers, Picasso infused his distinctive style into the heart of these art forms. Delving into his artistic endeavours beyond the easel, it is possible to uncover how his involvement with ballet and opera enriched these genres and further cemented his legacy as a versatile and innovative multimedia artist.

Picasso's Foray into the Performing Arts

Picasso expressed an interest in dance from an early age, which manifested in his circus dancers artworks of the 1900s. In the 1910s, Picasso would go on to contribute to ten ballet productions over the ensuing decades. Most of these were with the Ballets Russes, an itinerant ballet company conceived by impresario Sergei Diaghilev that operated between 1909 and 1929. The company is now considered the most influential of the 20th century, largely due to its avant-garde nature: it consistently commissioned and collaborated with groundbreaking artists, including musicians such as musicians Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, and Erik Satie, and artists such as Vasily Kandinsky and Henri Matisse, apart from Picasso himself. Even Coco Chanel acted as a costume designer for some of the company’s productions. The Ballets Russes is credited with reinvigorating the art and passion for ballet. Picasso was introduced to Diaghilev by writer Jean Cocteau, who was writing the scenario for Parade and was the artist’s neighbour in Rome. Picasso became so immersed in the world of performing arts that in 1918 he married Ballets Russes dancer Olga Khokhlova, who became his first wife and was one of his earliest muses.

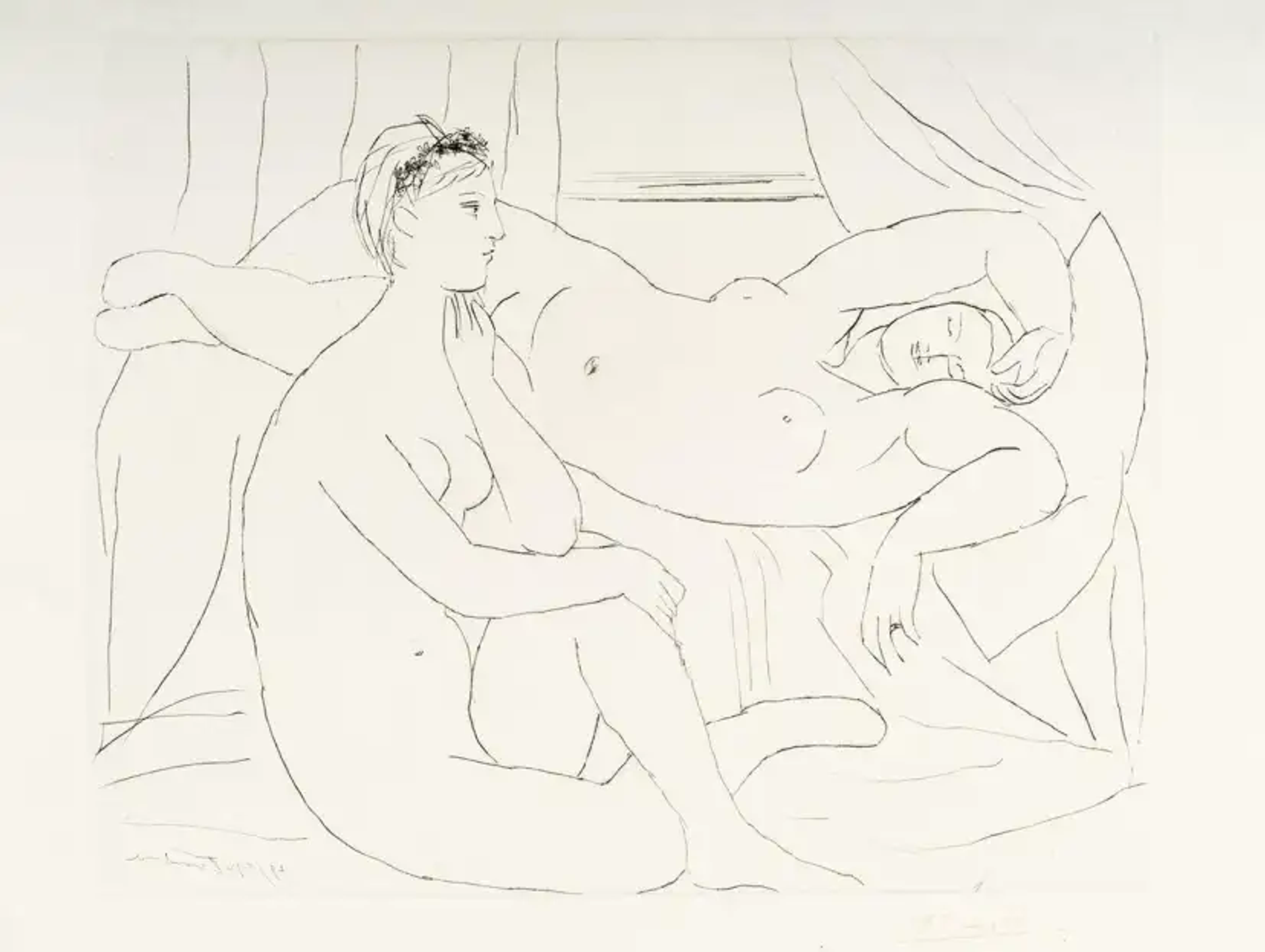

Picasso was involved in various aspects of ballet productions, from designing sets and stage curtains to crafting costumes. His last official involvement in ballet was in 1962, but the artist’s fascination with movement extended to the bacchanalian scenes he created between the 1940s and the 1960s. The dynamics of the dance thus impacted much of the artist’s work, sometimes going as far as fuelling his artistic expression itself.

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Parade Costumes, installation view of the exhibition Ballets Russes at the Bibliothèque-musée de l'Opéra de Paris 2010

Image © Creative Commons via Flickr / Parade Costumes, installation view of the exhibition Ballets Russes at the Bibliothèque-musée de l'Opéra de Paris 2010Parade (1917)

Picasso’s first official foray into ballet was for Parade, which was choreographed by Leonide Massine, with music by Satie and a one-act scenario by Cocteau. It premiered on May 18th, 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Picasso designed both the costumes and the sets for this production, which was the first-ever Cubist ballet. Other pioneering aspects followed: poet Guillaume Apollinaire described the ballet as "a kind of surrealism" when he wrote its programme, thus coining the word three years before Surrealism emerged as an art movement.

Parade’s plot revolves around a troupe of performers’ failed attempts to attract an audience to their show. It incorporated many popular entertainments of the period, and was set in the streets of Paris. The audience’s first impression of Picasso was the curtain he created for the production, which would be the artist’s largest ever work. It shows a group of performers on a stage while, to the left, a winged mare stands to the left with a suckling foal and a fairy perched on its back. Both Synthetic and Analytical Cubism then found their way into his contributions: the main set was a monochrome back cloth depicting a cubist perspective on a Parisian boulevard. The artist also created 2.75m tall sculptures, created out of geometrical shapes, to represent the characters of the Managers – their scale toyed with the perception of the dancers’ height. He also created a costume for a horse, and the dancers’ work largely consisted of footwork.

Reception to the original performance was very mixed, with sections of the audience loudly booing before they were drowned out by riotous applause. Much of the criticism was aimed at Picasso’s designs for the costumes, many of which were solid, allowing the dancers minimal movement. Nevertheless, Parade is now considered one of the best art performances of the 20th century.

The Three-Cornered Hat (1919)

A few years later, Picasso participated in The Three-Cornered Hat, also choreographed by Massine and commissioned by Diaghilev. Premiering in 1919, the ballet was set in Spain and featured many elements of Spanish dance – which obviously resonated with Picasso’s own heritage. The ballet is based on The Three-Cornered Hat by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón, a forbidden love story between a magistrate and a miller’s faithful wife. Setting the mood for this, Picasso created a monumental stage curtain, featuring a scene from his homeland: traditionally dressed women watching a rodeo while a young boy sells pomegranates. Behind, the set was pastel coloured, featuring a village landscape against a starry sky. He also created costumes for the ballet, heavily inspired by popular Spanish attire.

The stage curtain Picasso created hung in the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York for 55 years, but now hangs in the New York Historical Society Museum and Library, the largest Picasso in the United States.

Pulcinella (1920)

An adaptation of an 18th century Neapolitan play, Pulcinella is a classic comedy of errors, composed by Stravinsky – it ushered in his neoclassical period. Massine acted as central dancer and created the libretto and choreography. Once again, Picasso was tasked with creating the costumes and backdrop. The latter created some hardships for the artist as he was forced to redraw several times at the behest of Diaghilev. Ultimately, they settled on a scene of Naples at night, overlooking Mt. Vesuvius. His costume designs borrowed heavily from the original time period and Neapolitan folk traditions. The ballet opened at the Opera de Paris on 15th May 1920.

Image © Musée Picasso Paris / Deux Femmes Courant Sur La Plage © Pablo Picasso 1922

Image © Musée Picasso Paris / Deux Femmes Courant Sur La Plage © Pablo Picasso 1922Le Train Bleu (1924)

Yet another collaboration between Picasso, Diaghilev and Cocteau, this one-act ballet was choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska to music by Darius Milhaud. Set in the French Riviera, the performance features a cast of swimmers, tennis players and weightlifters – all of which were outfitted by Chanel. Picasso was significantly less involved this time, as Diaghilev and Cocteau only asked for his permission to replicate his 1922 painting Deux Femmes Courant Sur La Plage onto the stage curtain, which the artist agreed.

Image © Creative Commons / Promotional image for the London revival of Mercury 1927

Image © Creative Commons / Promotional image for the London revival of Mercury 1927Mercure (1924)

That same year, Picasso broke away from the Ballets Russes for the first time when he worked in Mercure, for which he designed the stage décor and costumes. The ballet was commissioned by the Soirées de Paris company, a short-lived attempt by Count Étienne de Beaumont to rival Diaghilev. Again working with Massine, this performance saw Picasso move away from Cubism, and his designs are often seen as an evolution into his Surrealist and Neoclassical phases. Based on the god Mercury, the ballet has little plot, mostly focusing on visual impact through a series of tableaux vivants. Instead, Mercury is said to be a veiled satire at Cocteau, who apparently exaggerated his role in the success of Parade.

Picasso designed a drop curtain with patches of muted colours suggestive of a landscape, which stood behind the painted figures of a guitar-playing Harlequin and Pierrot with a violin outlined in black. A lyre, the attribute of Mercury, lies at their feet. The set backdrops were largely monochrome, composed of movable parts that were rearranged by dancers. Controversy arose when Dadaists such as André Breton boycotted the performance. This would be Picasso’s last major foray into the ballet.

Le Rendez-Vous (1945)

Similarly to Le Train Bleu, Picasso was mostly uninvolved in the production, only giving permission for the company to replicate a curtain based on his existing design.

Image © Opera de Paris / Icare 1962

Image © Opera de Paris / Icare 1962Icare (1962)

In his final involvement with the world of ballet, Picasso painted the backdrop of the recreation of Serge Lifar’s Icare, inspired by the tragic tale of Icarus in Classical mythology. This shows a figure falling downwards while wearing wings, a pre-annunciation of what would come. This was a subject Picasso was familiar with, having approached it in The Fall Of Icarus from 1958, painted at the UNESCO headquarters.

After the Final Curtain: Picasso's Legacy in Ballet

Picasso's foray into the world of ballet marked a significant chapter in his career, showcasing his boundless creativity and his ability to transcend artistic mediums. His contributions to ballet were not merely extensions of his visual art, but were standalone masterpieces that blended his style with the fluidity and grace of dance. Through his innovative stage designs, costumes, and collaborations, Picasso left a mark on the ballet world, influencing generations of designers and choreographers. His legacy in ballet is a vivid reminder of his versatility as an artist and his profound impact beyond just the visual arts, but also the performing arts. Picasso's journey with ballet underscores the timeless nature of his work and cements his status as a true polymath, whose influence continues to inspire and resonate in the world of all art.