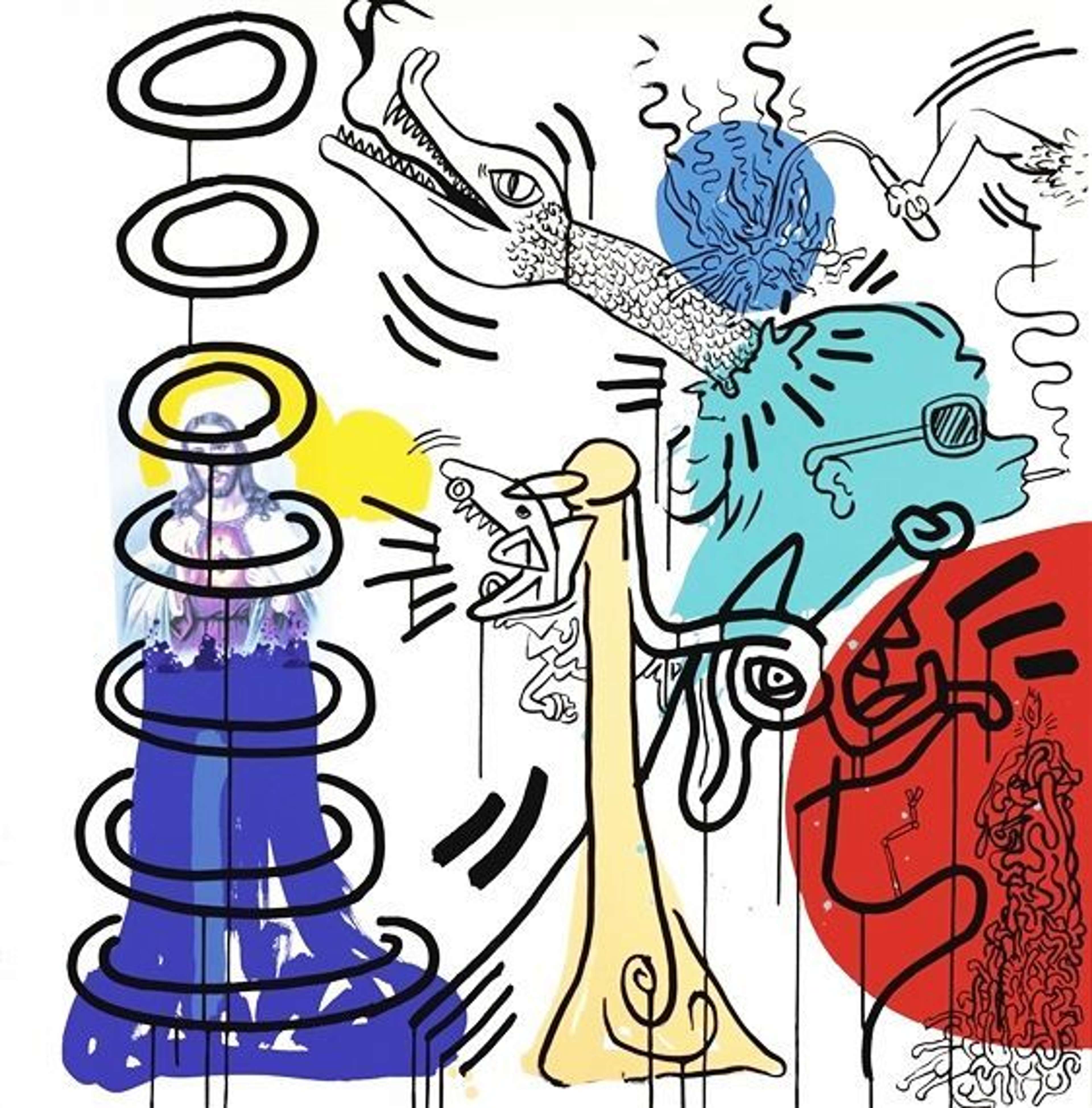

Chocolate Buddha 2 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 2 © Keith Haring 1989

Interested in buying or selling

Keith Haring?

Keith Haring

249 works

Keith Haring’s Chocolate Buddha series confronts the viewer with intricate patterns and interlocking creatures and objects. In his 1989 portfolio, Haring extends his inquiry into the problems of capitalism and mass media.

In Chocolate Buddha, Haring continued his shift away from simple and joyous subject matter.

Chocolate Buddha 1 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 1 © Keith Haring 1989The Chocolate Buddha series takes the features and tendencies of Retrospect even further. In the five prints the series consists of, the image of the human figure is hardly discernible. The individual human shape dissolves amidst the welder of swirling, densely accumulated lines, speaking of the pervasive effects of capitalism and mass media on the identity of the modern man.

Haring's experimental line carries a symbolic force.

Chocolate Buddha 3 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 3 © Keith Haring 1989Haring’s signature use of a thick, solid line comes to the fore Chocolate Buddha, capturing the artist’s ability to convey complex messages with austere means. Schematically outlined figures and shapes are interconnected in each of the five prints. Haring's line avoids creating clear boundaries between individual figures. As a result, outlines of shapes and figures seem to melt into one another, either bonding or entrapping one another.

Haring's Chocolate Buddha is far removed from its sacred prototype.

Chocolate Buddha 4 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 4 © Keith Haring 1989As the title of the series suggests, the ambiguous character vying for the viewer's attention isn’t exactly a figure of religious authority. Rather than Buddha, Haring depicts a no longer sacred surrogate of the spiritual teacher and thinker. Describing the figure specifically as the Chocolate Buddha, Haring positions it as a type of commodity, suggesting that capitalism erases the boundary between art and consumer objects.

Haring's dizzying world of shapes and colours mirrors the excesses of capitalism.

Apocalypse 5 © Keith Haring 1988

Apocalypse 5 © Keith Haring 1988Like many other Pop Artists of his time, including Andy Warhol, Gilbert & George or James Rosenquist, Haring took strong interest in the mass-produced imagery of popular culture. The Chocolate Buddha series is driven by a sense of paradox that comes from observing the world of mass culture and advertisement. The series challenges the idea of originality by taking recourse to a straightforward motif, bold colours, and techniques that reduce traces of the artist's hand.

Chocolate Buddha confronts us with the expressive potential of movement.

Chocolate Buddha 5 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 5 © Keith Haring 1989Many of Haring’s drawings feature simplistic human figures captured at a moment of movement. The figures appear immersed in the ecstasy of dance, which represents Haring’s way of paying tribute to the creative energies of the 1970s and 1980s, including hip-hop music. The chaos of interlocking lines in the Chocolate Buddha prints evokes a sense of movement, dance, and energy defining the urban setting in which both graffiti and hip-hop music flourished.

The figure of the Chocolate Buddha stands in opposition to the famous Radiant Baby.

Radiant Baby © Keith Haring 1990

Radiant Baby © Keith Haring 1990Although it may seem that the purpose of the interlocking shapes in the series is merely to confront the viewer with excess and chaos, at a closer look, many of them share visual affinity with the ‘devil sperm motif’. Towards the end of his life and career, references to sex and HIV/AIDS dominated Haring’s work, reflecting the process of coming to terms with the AIDS crisis and his own diagnosis in 1988. As a motif charged with themes of sexuality and death, the Chocolate Buddha stands in stark opposition to the lighthearted figure of Radiant Baby.

Chocolate Buddha reminds us of Haring's roots in street art.

Pop Shop VI, Plate III © Keith Haring 1989

Pop Shop VI, Plate III © Keith Haring 1989Haring’s use of simplistic, solid line defines both his early Subway Drawings and this late series. After moving from Pittsburgh to New York in 1978, Haring realised that the city offered him the opportunity to expand his artistic practice. As a result, he turned to city spaces and began to execute his drawings in chalk on black advertising spaces of the metro stations. Like the Chocolate Buddha prints, his drawings presented motifs consisting of simple lines – instantly arresting and easy to remember.

The series echoes the aesthetics of Art Brut.

La Chaise © Jean Dubuffet 1964 © Sotheby's

La Chaise © Jean Dubuffet 1964 © Sotheby'sThe accumulation of fluid, bold lines in each print in the series brings to mind the work of Jean Dubuffet. Haring once said of the founding father of Art Brut: “I was startled at how similar Dubuffet’s images were to mine, because I was making these little abstract shapes that were interconnected. So, I looked into the rest of his work”. The influence of the French artist on Haring’s generation has been profound and can also be traced across the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Haring’s close friend.

Haring's Chocolate Buddha series was produced through the medium of lithography.

International Volunteer Day © Keith Haring 1988

International Volunteer Day © Keith Haring 1988Haring produced the series through the medium of lithography, a printing process that utilises stone or metal to apply ink that then repels the pigment onto paper. Dating back to the 18th century, the printing process has the capacity to produce exceptionally meticulous details across a large number of multiples. The series represents Haring’s departure from the more commercial screen printing method that underscored his earlier work.

The series reflects Haring's desire to shatter the barriers between high and low culture.

Chocolate Buddha 2 © Keith Haring 1989

Chocolate Buddha 2 © Keith Haring 1989Each of the five prints included in the Chocolate Buddha series combines a simplistic, cartoon-like imagery with the unabashed energy of a child's drawing. Haring’s recognizable visual language rebels against the conventional distinctions between high and low culture. Reminiscent of the legacy of Jean Dubuffet, the presence of swirling scribbles and sinuous shapes in the series suggests that creativity can flourish through diverse types of artistic practice and beyond traditional art institutions and structures.