Where To Find Banksy’s Art: A Guide To His Most Iconic Locations Around The World

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Girl With Balloon © Banksy 2004

Image © Wikimedia Commons / Girl With Balloon © Banksy 2004

Banksy

270 works

Street art often takes advantage of its surroundings, using location and context to amplify an artwork’s message and impact. Banksy has long leaned into this mutual exchange; his art operating outside traditional gallery limitations and using that freedom to add layers of meaning that pieces in conventional museum settings don’t necessarily have access to. The theft of works like Banksy’s 2018 The Sad Girl highlights how removing graffiti from its intended site can strip that visual dialogue of its resonance and emotional force.

By nature, street art’s illegality confuses the boundary between public and private property. Can Banksy own his artworks if they're created on someone else’s property? This complicates the idea of location as a tool artists can control – their original intent may create one narrative, but once a work is removed or altered, that narrative is no longer in their hands. At the same time, part of street art’s allure is its ephemerality; its impermanence often becomes part of the story, and attempts to preserve and immortalise this transient medium can blunt that effect.

Image © LEX / The Mild Mild West © Banksy 1999

Image © LEX / The Mild Mild West © Banksy 1999Banksy in Bristol

The countercultural ethos of Bristol, with its longstanding history of activism, protest, creativity and independent music, undeniably shaped Banksy’s early voice. He began tagging the streets in Bristol in the early 1990s, in a city already known for its diverse and prolific street art scene. Eventually, he shifted towards stencilling, which allowed him to spend less time exposed on the street and to produce more complex artworks faster.

One of his early graffiti murals is The Mild Mild West (1999) in Stokes Croft, showing a teddy bear lobbing a Molotov cocktail at riot police – a tribute to Bristol’s history of protest. Another iconic work is Well Hung Lover (2006), a mural of a naked man dangling from a window while an angry husband searches for him, painted on the side of a sexual health clinic in central Bristol. It was the UK’s first legalised graffiti mural, granted retroactive permission by the city, and an early sign of Banksy’s growing global status in the art world.

As his style has evolved, Banksy has consistently returned to his hometown as a site for his art, producing works like Girl with the Pierced Eardrum (2014), which reimagines Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, the pearl replaced by a burglar alarm. Today, more than fifteen Banksy works can still be found around the city, functioning as tourist landmarks – their appeal amplified both by Banksy’s fame and by Bristol’s status as the artist’s birthplace.

Banksy in London

Perhaps his most recognisable mural, Banksy’s Girl With Balloon appeared in Shoreditch in 2002, accompanied with the short slogan; “there is always hope.” Its simplicity and sincerity resonated widely, and it has since become one of the defining art images of the 21st century. In 2017 it was voted the UK’s favourite artwork according to the BBC, and a year later, its fame peaked again when the work was partially shredded in its frame during a Sotheby’s auction – a stunt that made global headlines and increased its value from £860,000 to £1.04 million (with fees).

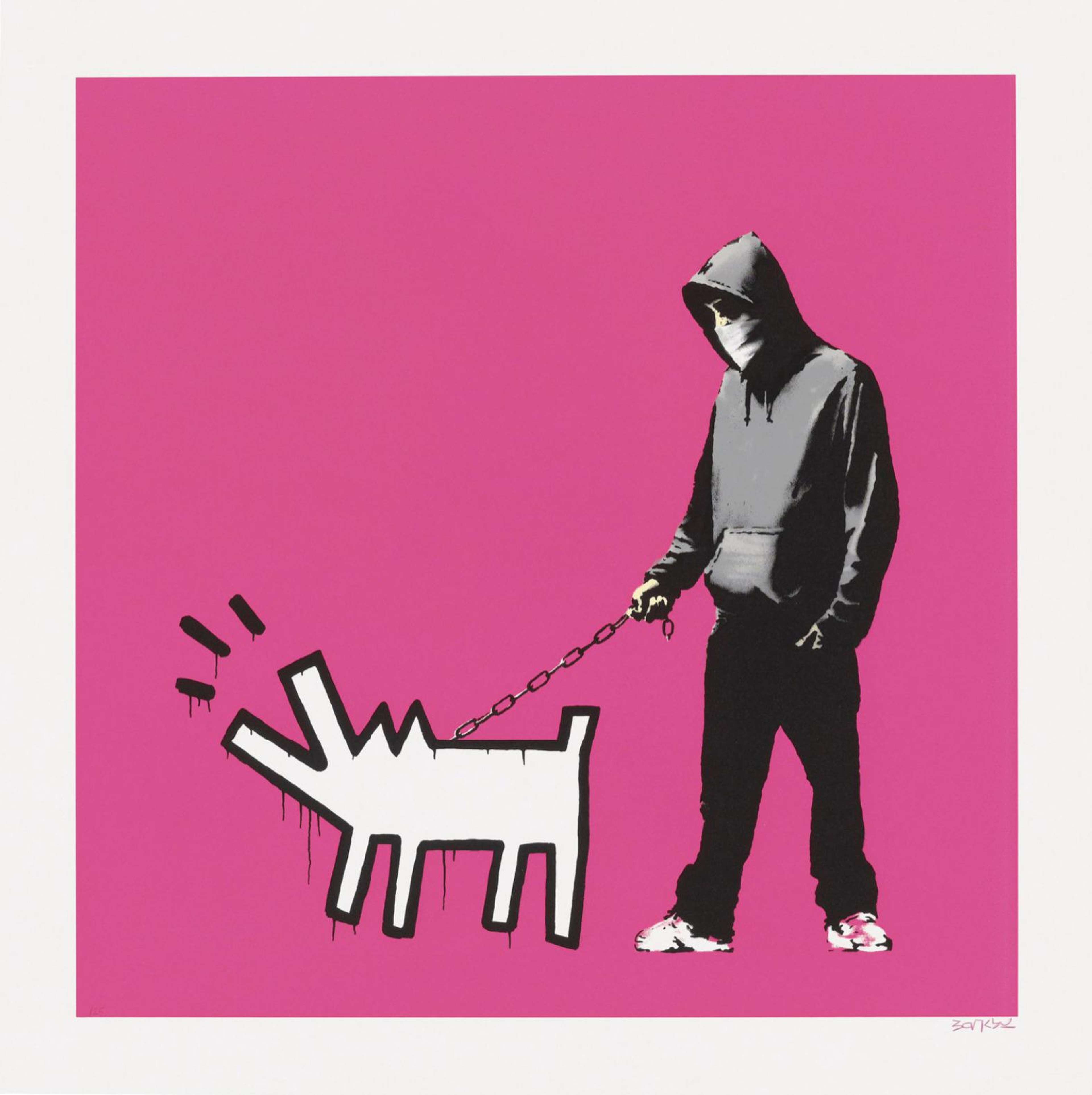

Banksy has often used London’s vast, cosmopolitan landscape as a backdrop for his art, and his murals in the city frequently confront its contradictions, inequality and consumerism. Choose Your Weapon first appeared in south London in October 2010 on the side of The Grange pub in Bermondsey. The piece comments on Britain’s alienated youth and gang culture, where status and control are bound up with the image of dangerous dogs. The dog’s form deliberately appropriates Keith Haring's style, the childish outline underlining how detached this symbol is from the real harm that weapons can cause. Echoing media panic around so-called status dogs, Banksy’s mural suggests the animal has become a stand-in for knives or guns on UK streets, nodding to rising gang violence and the fashion for training dogs to attack. By turning man’s best friend into an accessory to violence, the work becomes a bleak portrait of disaffected youth in contemporary Britain.

A year later, in 2011, Shop Until You Drop mural, one of his best-preserved pieces, appeared in Mayfair and depicts the silhouette of a woman plummeting while clutching a shopping trolley. The work satirises the consumption that defines one of the city’s wealthiest shopping areas. As Banksy himself has said: “We can’t do anything to change the world until capitalism crumbles. In the meantime we should all go shopping to console ourselves.”

More recently, Banksy’s London Zoo murals appeared across the city over nine days in the summer of 2024. An urban safari including wolves, leopards, a rhino and three monkeys appeared on bridges, satellite dishes, a fish and chip shop, and even the shutters of London Zoo. Each new animal exploded online and sparked waves of speculation, reminding London how effortlessly Banksy can turn the streets into his canvas. With no explanation offered, and readings ranged from social commentary to environmental and animal-rights concerns, while others interpreted the creatures as stand-ins for human chaos and unrest after recent riots. The broader impression, though, is that these works were designed to inject a flash of humour and delight into the city’s daily routine.

These murals are just a few of Banksy’s many London works, and they show how profoundly location can shape the meaning of a piece – the city itself becoming an active part of the artwork through its identity, culture and politics.

Banksy Across the UK

Banksy’s murals are not confined to Bristol and London; his work has appeared across the UK, from the steel town of Port Talbot in Wales to Margate on England’s east coast. In 2018, Season’s Greetings appeared in Port Talbot, showing a child catching what looks like a snowflake on his tongue, only for the “snow” to be revealed as ash falling from a fire – a reference to industrial pollution from the town’s nearby steelworks. The artwork spoke powerfully to environmental anxieties as well as the community’s pride in its industry. Eventually, Season’s Greetings was bought for a six-figure sum by an art dealer and, after a few years, relocated to an English museum. The move sparked public outcry, encapsulating the ongoing dilemma between preserving street art and keeping it embedded in the communities it was made for.

In February 2023, a mural later titled Valentine’s Day Mascara appeared on the side of a house in Margate, depicting a 1950s housewife caricature with a black eye, cheerfully stuffing her abusive partner into a real freezer installed on the street – a dark Valentine’s message about domestic violence. Banksy’s use of a prop quickly became a problem for local officials, and within hours the council had removed the broken freezer, effectively dismantling part of the artwork. Later, the whole piece was taken from the wall for preservation, and it is now displayed in Margate's amusement park, its domestic horror repackaged as a seaside attraction.

Banksy has also left his mark in the East Midlands; a mural appeared in Nottingham in October 2020 showing a young girl hula-hooping with a bicycle tyre beside a real bike locked to a post with its back wheel missing. Eventually titled Hoola-Hoop Girl, the piece suggests that even against the backdrop of a pandemic and mounting social anxiety, joy can still be found in whatever is left lying around – a reminder that happiness sometimes survives in the smallest moments. As with so many of his interventions, the work quickly became a local landmark.

Banksy Abroad

Banksy in Palestine

Banksy’s practice has never been limited by national borders, and he treats international locations as extensions of his canvas to sharpen the politics already embedded in his work. His most ambitious site-specific project to date appeared in 2017 with The Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem, built just metres from the Israeli separation barrier. Half artwork, half functioning hotel, inside guests found themselves surrounded by original Banksy pieces – from a pillow-fight between an Israeli soldier and a Palestinian protester to more sombre commentaries on the realities of occupation. Banksy had first visited the West Bank in 2005, leaving stencils on the barrier, including his now-iconic Flower Thrower. With the Walled Off Hotel, those interventions evolved into a more permanent form of cultural diplomacy, confronting visitors with the everyday conditions in Palestine. More recently, since the escalation of conflict in the region, the hotel was shut down in late 2023, promising it was only “for the time being.”

Banksy in New York City

Banksy has also used temporary “residencies” abroad to play with the possibilities of location. In October 2013, he unleashed Better Out Than In, a month-long intervention across New York City. Each day a new work appeared unannounced somewhere in the five boroughs: stencils down alleyways, slogans in plain sight, and even a slaughterhouse delivery truck carrying sixty stuffed animals. New Yorkers treated it like a citywide treasure hunt and, most famously, a Central Park stall sold authentic Banksy canvases for $60 to unsuspecting passers-by. By choosing New York, a city he said “calls to graffiti writers like a dirty old lighthouse,” Banksy folded the city’s personality into the artwork itself. Some murals were immediately defaced, others preserved behind plexiglass, and the shifting public response became part of the story, underscoring his point that street art only truly exists through its dialogue with the people who live around it.

Banksy in Ukraine

In November 2022, Banksy’s art appeared in Ukraine with a series of stencilled murals that read as small acts of resistance. Scattered across bombed towns and suburbs such as Borodyanka, Irpin, Hostomel and Kyiv, the works combined his usual blend of wit and critique to comment on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The images depicted a gymnast balancing on the rubble of a ruined tower block, a child throwing a judo master who resembles Putin, children using a tank trap as a see-saw, an old man washing in a bathtub inside a shelled building, and a housewife in curlers wielding a fire extinguisher in a gas mask. Each image staged the clash between everyday life and war - the child and judo master artwork was later chosen for a Ukrainian postage stamp. Together, the series of images narrated the weight of survival, defiance and the desire for normality amidst devastation.

Visiting Banksy’s Art

Over the past three decades, Banksy’s work has become a network of global tourist attractions. Guidebooks, street art tours, and digital maps now chart his murals across cities, and this “Banksy tourism” speaks to a broader acceptance of street art as cultural heritage. At the same time, his popularity has made the works increasingly vulnerable to damage, theft, and relocation. In 2008, Banksy’s team set up Pest Control, an official body to authenticate works – and it refuses to certify pieces removed from walls, a policy designed to deter collectors from vandalising property for profit. Even so, in late 2023, just hours after Banksy confirmed a new stencil of three drones on a London stop sign, thieves cut down the sign and ran off with it.

Ultimately, Banksy’s locations matter because they turn passive images into interactive encounters. The ongoing stories of his artworks appearing, disappearing, and travelling are all part of a larger narrative about art’s role in society – and who gets to own it.