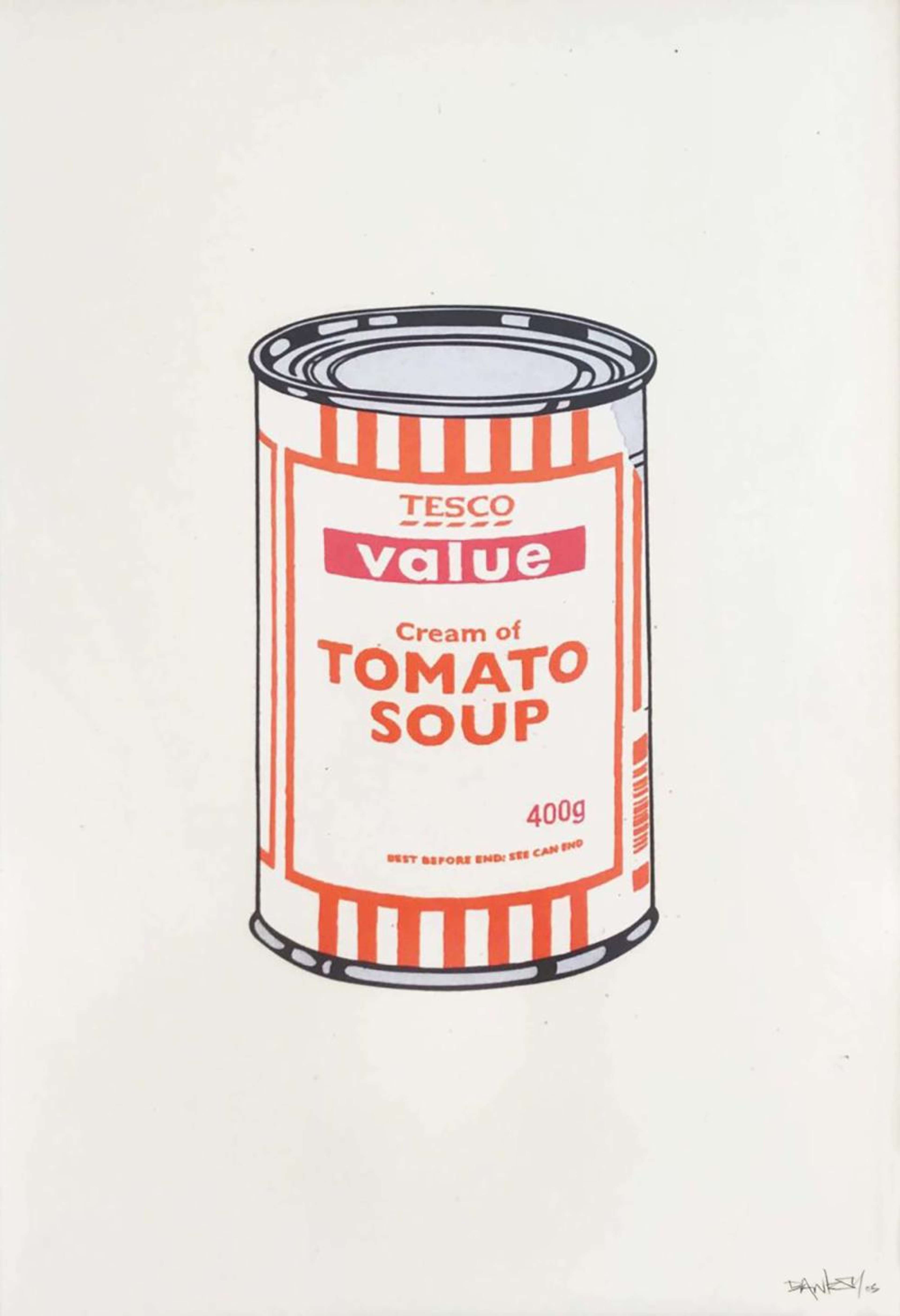

Soup Can (white, orange and raspberry) © Banksy 2005

Soup Can (white, orange and raspberry) © Banksy 2005

Banksy

270 works

As many of his tongue-in-cheek artworks suggest, Street Art sensation Banksy is well-known for poking fun at art history, and for complicating the relationship between traditional and non-traditional art.

Realising record-breaking sale prices when his work goes under the hammer, some would argue that the acclaimed, Bristol-born street sprayer may now in fact be part of the same art historical establishment he loves to critique — although we’re sure he wouldn’t like to admit it.

Banksy's most frequent challenge to the canon is an accusation of elitism and conformity to the niceties of bourgeois taste. He takes up arms against highly conventional art, such as a pastoral landscape or religious painting, which, unlike his own work, bolsters rather than subverts hegemonic ideals.

Despite this, when picking artists for his reworkings of canonical oil paintings, Banksy often picks artists who had, at least in their own lifetime, outsider status: Monet was once seen as too radical, van Gogh was institutionalised, Basquiat was widely uncelebrated as a gay, Black man who ultimately died from an accidental overdose. In all likelihood this is because Banksy is more critical of the commercial and critical art worlds that retrospectively assimilated these artists into the canon, suppressing their differences, and receiving the vast profits that the artists never saw. This is a sentiment Banksy has often expressed, whether in his print, Morons, or by posting the following quotation from art critic, Robert Hughes, to his Instagram:

In this article, we take a deeper look at Banksy’s key references to canonical artworks, as well as his disruption of traditional art practices and histories.

Show Me The Monet © Banksy 2005

Show Me The Monet © Banksy 2005Crude Oils (2005)

In October 2005, Banksy unveiled his Crude Oils exhibition, which took place inside a shop in Westbourne Grove, West London. For the exhibition, this tiny space was filled with 200 live black rats, prompting a visit from local health authorities.

Rodents aside — the artworks on show were 20 reworkings of famous oil paintings by key canonical artists, including Warhol, Monet, Hopper, and van Gogh. Many of these takes on canonical works undermined the conventional aesthetic ideal of art as beautiful: irrespective of whether Monet and van Gogh intended their works to be justified solely on their beauty, Banksy's 'corrections' to the paintings suggest that he believes art should instead be valued for its relation to reality, and its apt political commentary.

Amongst these ‘Banksy-fied’ works were two of the artist’s most famous: Sunflowers From Petrol Station — Banksy’s third-most expensive work as of 2021 — and Show Me The Monet, which in 2020 sold for nearly £7.6 million.

Of the two, Sunflowers From Petrol Station is particularly Banksy-esque. The piece stands as a cornerstone of Banksy’s hand-painted oeuvre, a rarity amid his graffiti-centered works. Its humour and pathos make it emblematic of his broader concerns: pollution, the elitism of institutionalised art, and the hypocrisies of consumerism. Removing all traces of bucolic charm from van Gogh’s sunflowers, Banksy paints a wilted, neglected posy one might expect to find in a petrol station. A particularly accurate evocation of the British retail experience, the work is far more garage forecourt on the M25 than it is Arles 1888. Banksy’s choice to parody van Gogh, a figure synonymous with artistic passion and authenticity, underscores the irony of today’s art market. While van Gogh’s work struggled for recognition in his lifetime, his Sunflowers later fetched millions, inspiring Banksy’s print Morons, which mocks the absurdity of art-world commodification.

To Monet's Bridge Over A Pond Of Water Lillies, Bansky adds a littering of shopping trolleys and a traffic cone. His Show Me the Monet revises the original celebration of natural beauty with an observation of the state of the environment at present, and a critique of the forces behind that state—namely, capitalism, as usually signalled by Banksy's trolley motif.

(For a rundown of all Banksy exhibitions since 2000, see our article here.)

Subject To Availability © Banksy 2009

Subject To Availability © Banksy 2009Vandalised Oils (2009)

Later, in 2009, Banksy unveiled a similar series named Vandalised Oils. Contemporary re-imaginings of canonical paintings, the works in the series are all complete with Banksy’s deeply mocking, satirical flair.

Subject To Availability is the most highly regarded work in the series. It takes its cue from an 1890 oil painting of Mount Rainier National Park, Washington State, USA, painted by Albert Bierstadt — a German-American artist who mostly painted the American West and its ‘wild’, expansive beauty.

The difference between the Banksy and the Bierstadt? Banksy’s version includes a cheeky footnote: ‘Subject to availability for a limited period’.

A clear nod to the devastating impacts of climate change, Banksy’s painting not only toys with the canon: it ridicules our taste for the placid and beautiful, and our inaction in the face of an existential threat that we have the power to prevent.

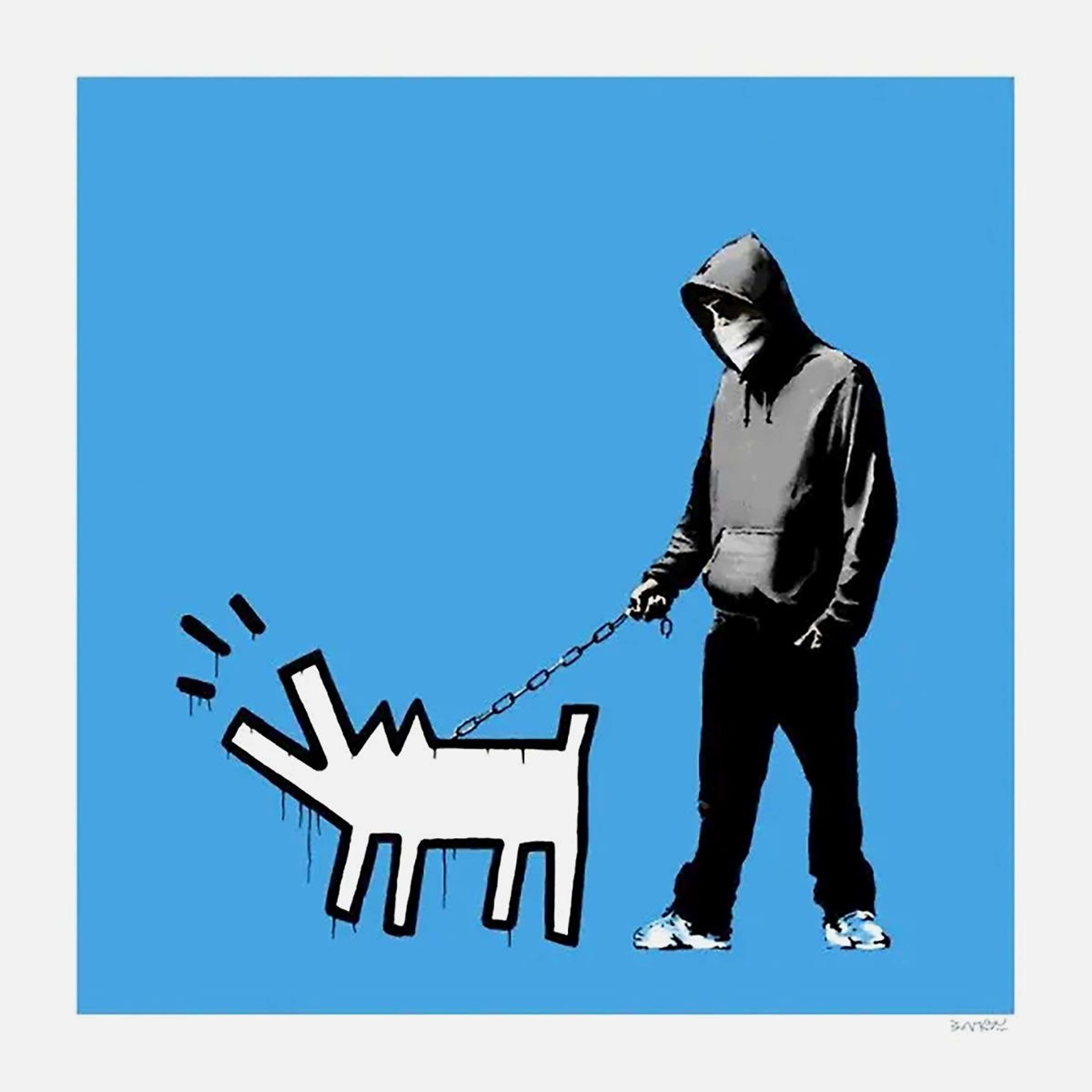

Choose Your Weapon

A standout feature of Banksy’s œuvre, Choose Your Weapon first appeared on the walls of The Grange Pub in Bermondsey, South East London, in 2010. It has since appeared in a number of original prints by the artist, released via now-defunct print house, Pictures On Walls.

Featuring a hooded, masked figure — not unlike that portrayed throwing flowers in Love Is In The Air (Flower Thrower) — the work co-opts a well-known icon typically associated with another canonical street artist: Banksy’s self-avowed hero Keith Haring.

This icon is Haring’s Barking Dog motif, which was first featured in the artist’s famed New York Subway drawings. In Banksy’s design, Haring’s dog is shown at the end of a lead held by the masked figure.

The Barking Dog has been hailed as a symbolic call to arms; expressing urgency and danger, it communicates the need to speak out against political and social injustice. In this instance, the agreement of Haring and Banksy's message suggests that Banksy is not critical of this canonical figure. Rather, if he is critical of art historically, here, it is of the unwillingness of other individual artists to share their ideas and collaborate towards the world their art dreams of. So often, when an artist has been placed on a pedestal by the art world, it is assumed that if it were proven that they had help in their artistic process, their artistic integrity would be compromised: Banksy shows us that this is not the case.

It’s not too difficult then, to see why Banksy incorporated the motif into Choose Your Weapon. Eminently political, many of Banksy’s works have sought to raise awareness of a range of iniquities: from global warming, international conflict, and the refugee crisis, to the underfunding of the UK’s National Health Service, police violence, and beyond. Aligning himself with those artists who came before him, Banksy champions the notion of art as a political tool for good.

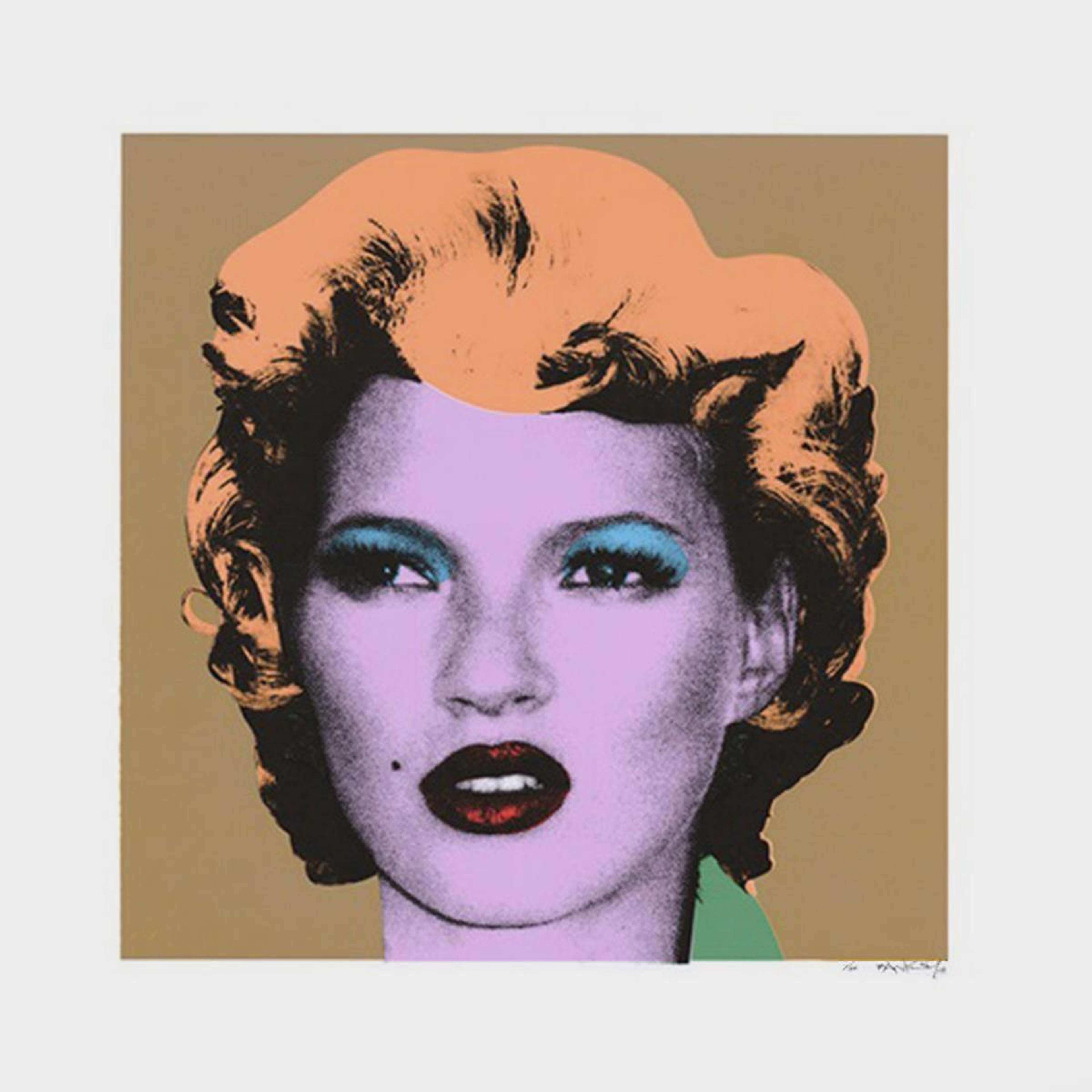

Kate Moss and Soup Can

In two other series, Banksy directly references the work of Pop Art kingpin, Andy Warhol.

In Kate Moss, he nods to Warhol’s seminal Marilyn Monroe and Mao paintings, created in their majority during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

To create these images, Warhol would take a photograph with a Polaroid camera before tracing it onto drawing paper with an overhead projector. With the source image transformed into a variety of simple, economical lines, Warhol would fill the work’s negative space with bold, uniform sections of colour.

This almost mechanised process, which recalls that later used by Damien Hirst, allowed Warhol to create huge numbers of bold images quickly and efficiently. Sound familiar? Well, it’s an outcome not too dissimilar from that afforded by Banksy’s much-loved stencil.

Replacing one American icon with a British equivalent, Banksy depicts Moss in a variety of hues, including apricot and gold, blue and grey, pink, dark pink, and purple, copying Warhol’s composition almost exactly.

In May 2022, one of Warhol’s Monroe paintings — Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964) — sold for US$195 million (£158 million) at Christie’s New York, making it the most expensive piece of 20th-century art ever sold.

In Soup Cans, Banksy makes visual allusions to another of Warhol’s most well-known subjects: the humble Campbell’s Soup Tin.

Substituting this symbol of working-class America for a pointedly British analogue, Banksy turns his attention to the Tesco Value range — a mainstay of the British supermarket scene during the 1990s and 2000s, instantly recognisable for its no-frills ‘blue lines’ design. Banksy's approach to Warhol's canonical artworks is to update them to a contemporary frame of reference, and to show how consumerist culture has preserved and adapted itself against time.

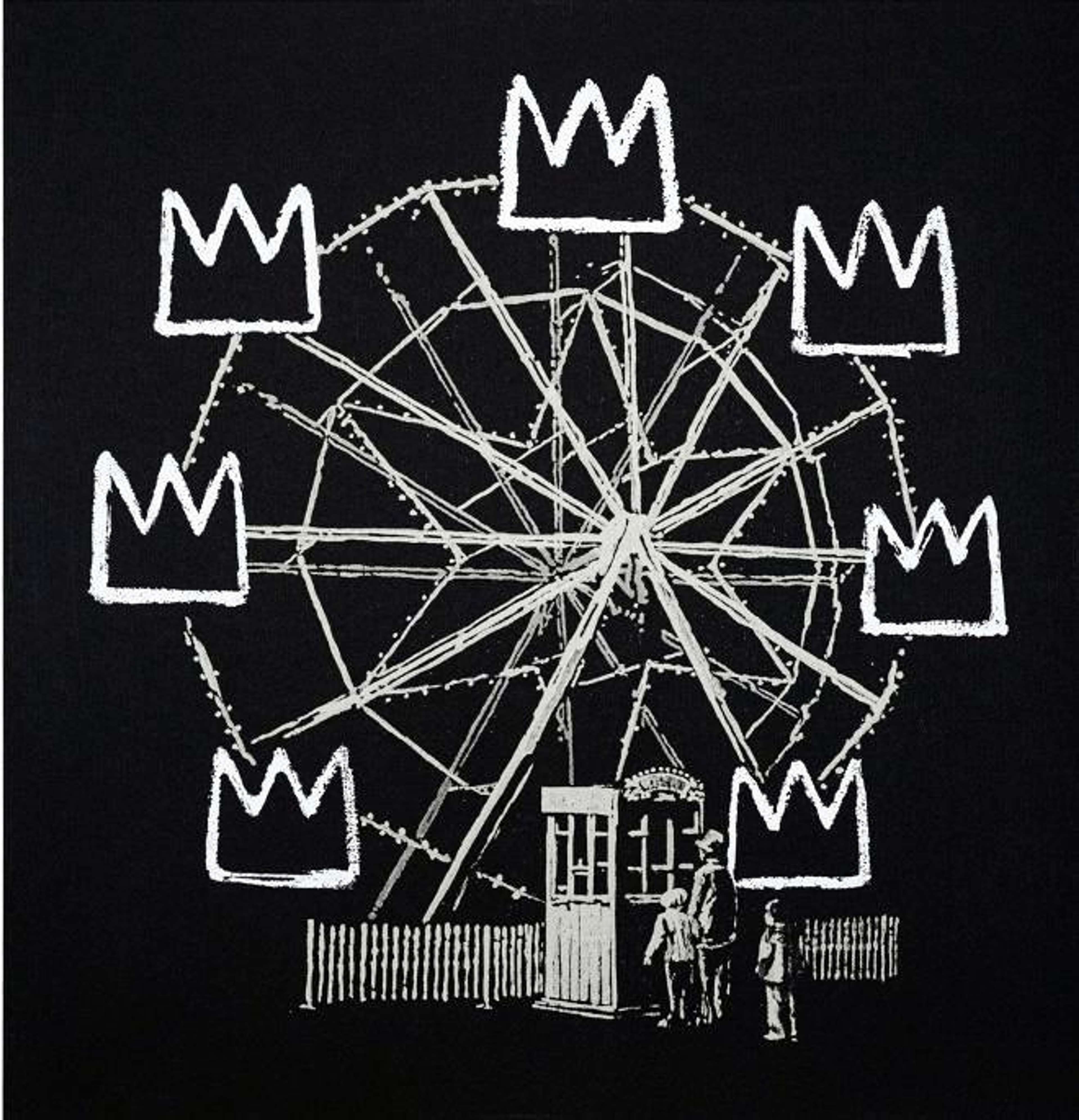

Basquiat and the Barbican

In 2017, Banksy painted a new design onto the walls of London’s Barbican Centre to mark the opening of an exhibition of works by American artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Borrowing from Basquiat’s 1982 painting, Boy And Dog In A Johnnypump, the piece depicts a figure being stopped and frisked by a pair of overzealous police officers. When posted to Banksy’s Instagram account, the piece was captioned: ‘Portrait of Basquiat being welcomed by the Metropolitan police — an (unofficial) collaboration with the new Basquiat show.’

Marrying Basquiat’s unique, sketch-like visual style and his own stencil-based approach, Banksy shows his love for the eminent American artist, who died of a heroin overdose in 1988, aged just 27.

Intertwining high and low art, and referencing the pair’s shared origins as humble graffiti writers, the painting is a pointed critique of police ‘stop and search’ powers. Placing the revered Basquiat in the position of a police suspect, Banksy also calls for renewed attention to the far-reaching damage caused by structural racism.

The untitled mural was accompanied by another smaller-scale work depicting a queue for a Ferris wheel complete with three-pronged crowns: important motifs in the scheme of Basquiat’s œuvre. As is boldly apparent with this second work, Banksy takes up with Basquiat in homage, and is evidently an admirer. By producing an 'unofficial' contribution to the exhibition at the Barbican, which is undoubtedly a canonical institution, Banksy also hopes to remind us of the similarly unofficial, uncanonical roots of Basquiat's work.

Banksy in Paris

A parody of Le Premier Consul franchissant les Alpes au col du Grand Saint-Bernard (1801-1805), painted by neo-classical painter Jacques-Louis David, ( teacher of world-famous Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres — the chief inspiration for David Hockney’s camera lucida portrait series, this piece appeared in Paris, close to the city’s Bassin de la Villette in the 19th arrondissement.

Atop a majestic horse is the figure of Napoleon, who rather than wearing his characteristic bicorne hat is covered by a red drape. Obscuring his vision, this piece of cloth appears to reference a controversial French law, passed in 2011, banning the wearing of face-covering headgear (including the niqab and burka) in public spaces.

David’s original painting — which Banksy’s stencil-based artwork parodies —serves as a visual metaphor for French military prowess and progress; in it, Napoleon gestures forward, over the Alps, with a pointed finger.

By contrast, the figure in Banksy’s painting is powerless to move forward, his path hidden from view. An allegorical painting for the 21st century, we can read it as a dig at France’s less-than-progressive politics in recent years, as well as European nations’ unfortunate tendency to glorify their pasts.

Banksy's Rats

Whether knowingly or not, Banksy’s œuvre also makes plenty of references to a key figure in the non-traditional art establishment: Xavier Prou, better known as Blek le Rat.

Dubbed the ‘father of stencil graffiti’, Blek le Rat is among the first known street artists in Paris. Active since 1981, he is best recognised for stencilling images of rats throughout the French capital. While they certainly bear all the hallmarks of Banksy’s works, Love Rat, Radar Rat, and Because I’m Worthless are arguably indebted to Blek’s approach.

Despite their similarities, however, there is no animosity between the pair; they have even expressed their desire to collaborate with each other on stencil-based artworks in the future.

Browse our Banksy prints for sale or get a valuation here.