Flowers (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1964

Flowers (F. & S. II.64) © Andy Warhol 1964

Interested in buying or selling

work?

Live TradingFloor

Artists have been producing print editions for many millennia, and these offer brilliant investment opportunities as well as their own rich art history, craftmanship, innovation and tradition. In this guide we take a look at some of the most important print mediums, how prints are made, and how to recognise a print's medium.

What is a print?

A print is a work of art that exists in many, identical impressions. As a rule, prints are often made by running plate and paper through a press, and medium genuinely refers to the different techniques and materials used to make the plate carry the image, but, as we shall see, there are exceptions to this rule. The advent of many technological innovations, including digital printers but also the discovery of photosensitive materials has contributed to this wealth and variety of printmaking methods.

Artists may make their prints alone, but often they will have worked in collaboration with professional printmakers, or employees if they have their own studio.

A Brief History of Printmaking

Printmaking techniques can be traced back to 206 B.C. in Ancient China with a longstanding reputation for combining craftsmanship with technology. The Middle Ages witnessed the rise of woodcut illustrations in books and religious manuscripts, while the Renaissance saw the emergence of intricate engravings and etchings.

The process of printmaking, in its simplest form, involves the transfer of images from a matrix, usually glass, wood or metal, to another surface. More often than not, these surfaces will be fabric, paper, metal, or wood. Different solvents or methods of application are what allow for a variety of printmaking techniques and aesthetic effects. The continued use of printmaking in the present day is an indicator of its value in the nuanced world of art production, and as a prized collectible for art collectors.

If you'd like to learn more about print edition terms, read our glossary here.

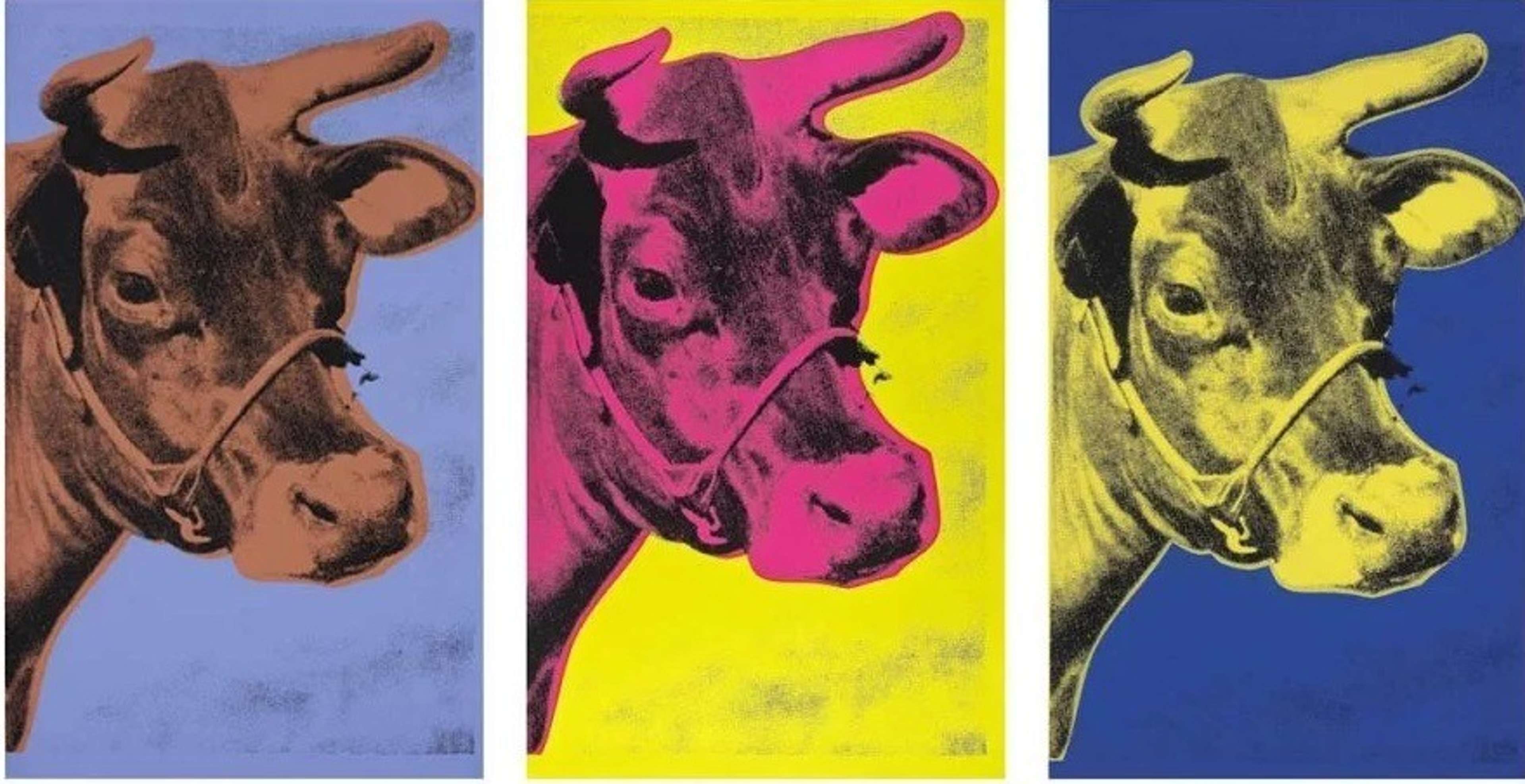

Cow Series © Andy Warhol 1966-1976

Cow Series © Andy Warhol 1966-1976Why do people collect prints?

Original or limited-edition prints are much more than a reproduction or a poster. For Pop artist Andy Warhol, printmaking was a favourite technique and many of his best-known works only exist as prints. Other artists, like Jeff Koons, used printmaking, multiples and editions to experiment with new ideas, taking the existing designs of his originals as only the starting point.

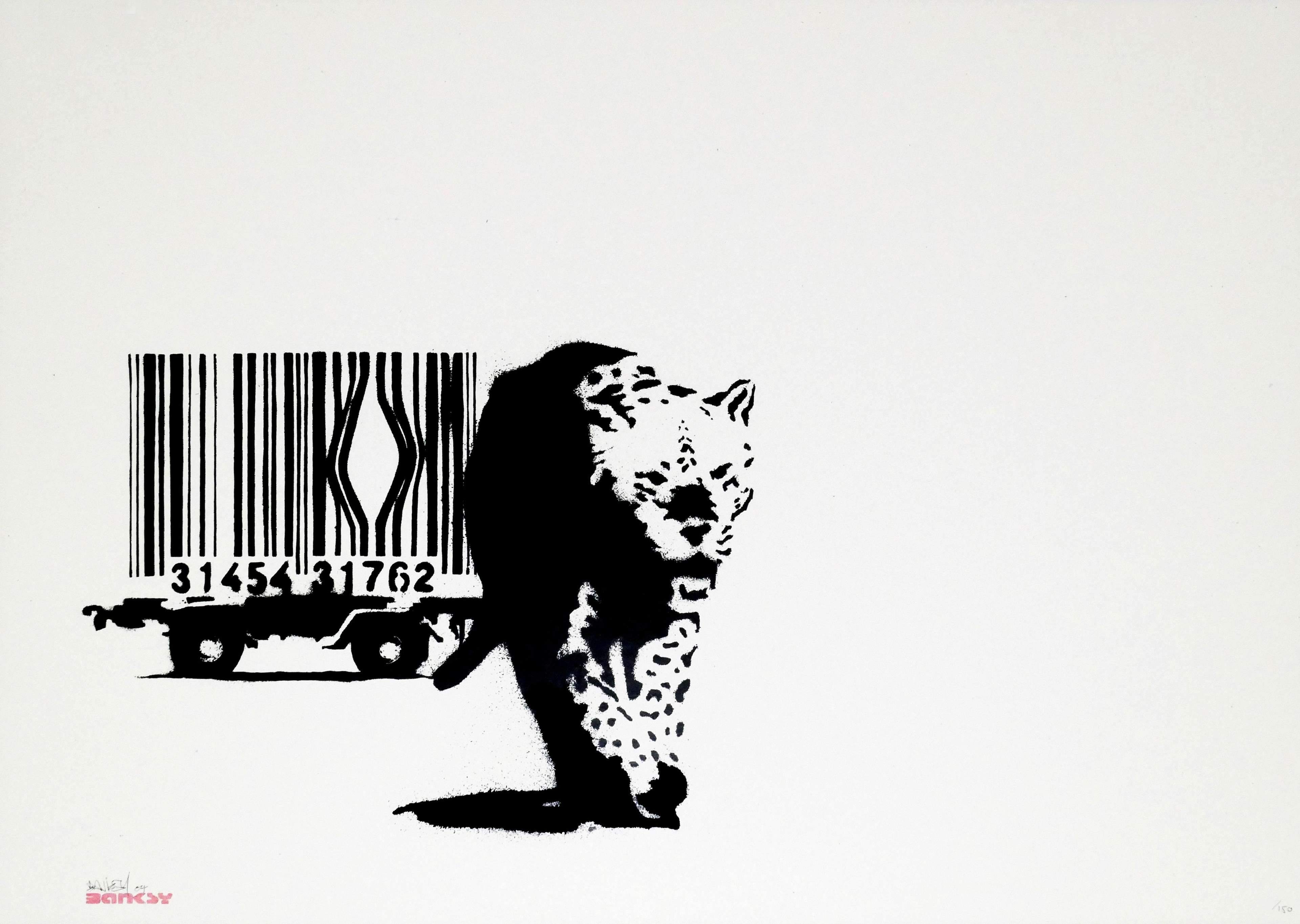

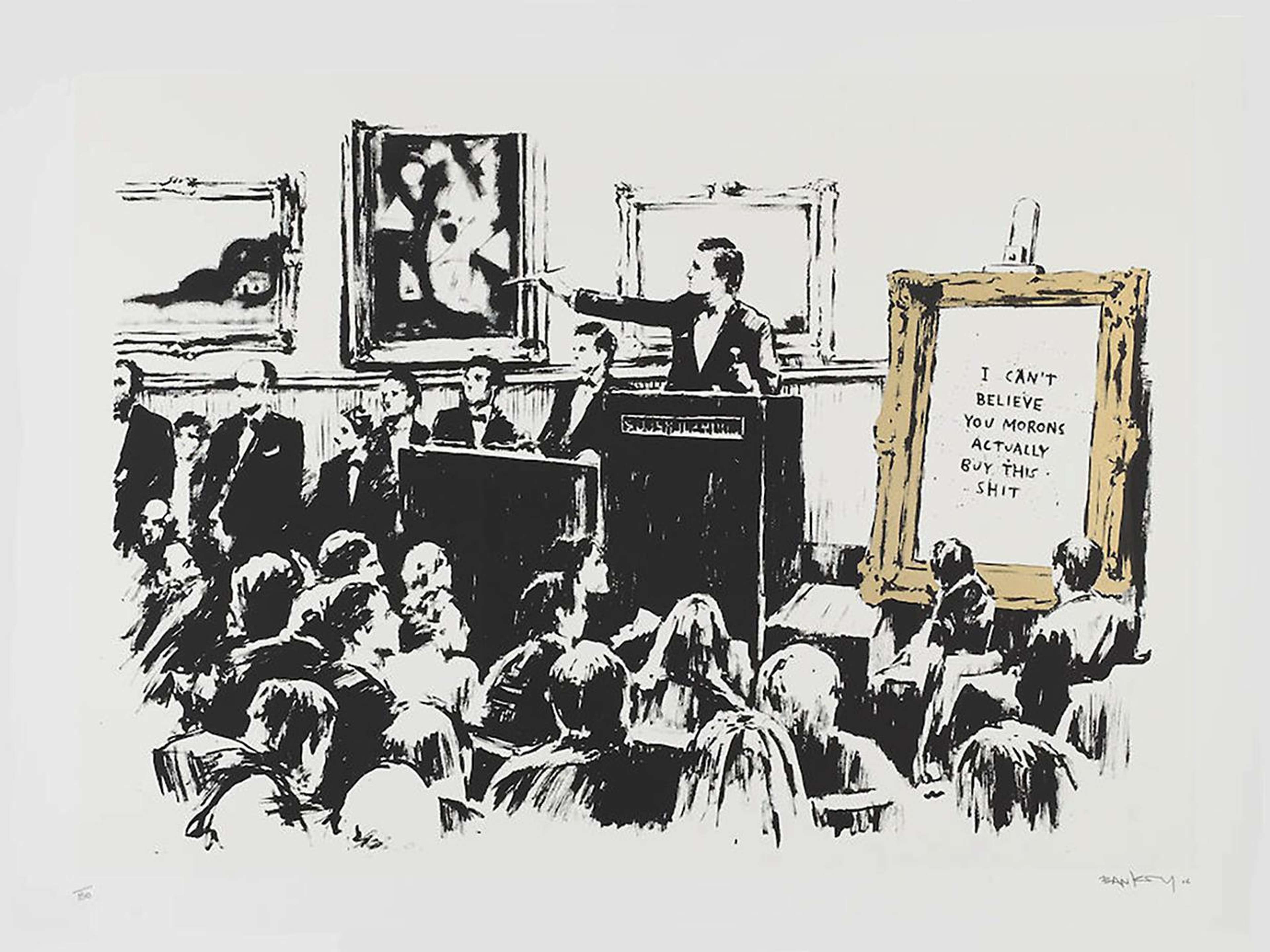

Investing in prints can be extremely profitable: Banksy is the perfect example – the artist originally sold signed editions of Girl with Balloon for £150 back in 2004 – they now regularly fetch well over £200,000 on the secondary market. A purple AP sold in September 2020 for £791,250.

What is print medium in fine art?

The medium of a print is the combination of methods and materials used to in its creation. Just as for original artworks, where a painting might be in the medium of oil or of acrylic, prints have their own different mediums. It can be very useful to be able to tell the difference between print mediums, especially when it comes to authenticating a work, knowing how to preserve it, or deciding what artists’ work you like. Our modern and contemporary print specialists will always be happy to help verify a print’s medium, value, or authenticity for you— you can get in contact with us here.

The following are among the most popular print mediums today:

Glossary of Print Mediums

AQUATINT

Aquatint is an excellent method for producing rich tonality— deep, solid areas of shadow and gradient— used in conjunction with etching. Following the same basic process as etching (see later), in the aquatint process the applied medium, a solution which evaporates leaving a gritty deposit, or a rosin sprinkled and melted onto the plate, acts as the acid resist. The method cannot be used to produce linework, but it does enable a watercolour-like control over shadows and gradient shading, that is incomparable to the hatching used to produce shadow in other mediums. As a result, prints with aquatint are instantly recognisable in the works of artists such as Picasso, by the deep and consistent areas of shadow, and smooth gradients. They can also be identified under a magnifying glass by the characteristic texture of the shading, which is made up of tiny rings, where the acid eats around the applied granules.

DIGITAL OR GICLÉE

The most common form of fine art prints today are Giclée prints. They employ ink-jet printers of a higher quality than household printers in order to create beautiful, high-definition art prints that last a very long time with little to no fading. They are commonly used to reproduce an original painting or drawing by an artist as they can minutely replicate the same dynamic range of colour and detail.

Initially, there was a great deal of bias against digital prints in the commercial art world, as they were seen as requiring no skill or craftmanship to produce, and do not bear the marks of manual labour by an artist and printmaker that some see as ‘authenticating’ it. Largely this bias, which emanated from the same quarters as criticism of early digital art—art that is designed digitally— reeks of conservatism for its own sake. Once upon a time, even photography was not considered as ‘real’ art, simply because the use of a more technological tool as opposed to, say, a paintbrush was seen as cheating.

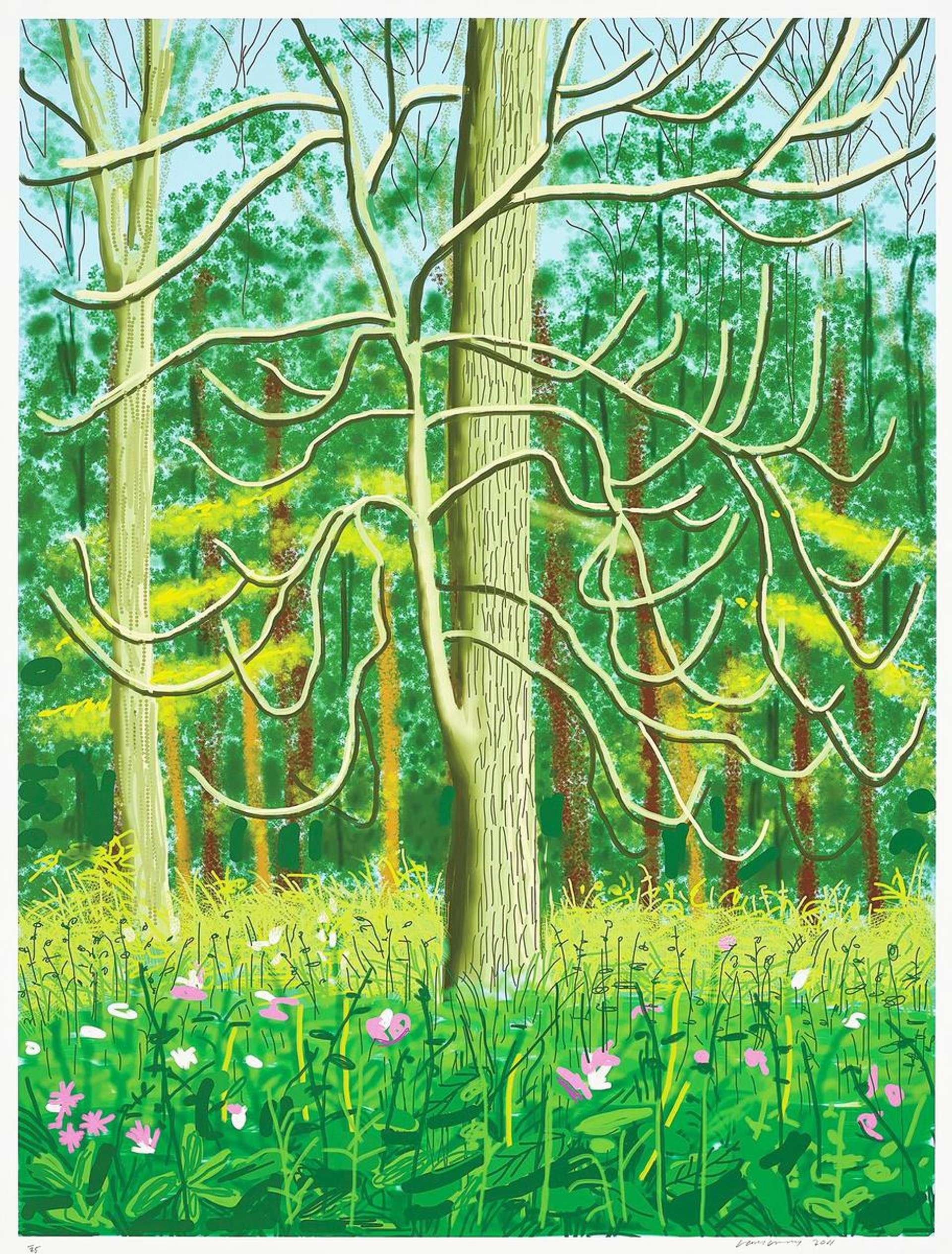

Thankfully, times have changed, and just as David Hockney’s iPad drawings are now celebrated in museums for the artistic skill they display, digital prints too have been afforded enough credibility to become a common and valuable means of producing editioned prints for many famous artists. As well as Hockney, Julian Opie is another artist who has created editioned digital prints.

While Warhol never produced digital prints for sale, the willingness of a true artist to embrace new technology can be learnt from an anecdote about how he became fascinated with the potential of new technology to mass reproduce images. While at the School of Visual Arts, Warhol discovered a xerox machine in the school’s supply department; he pressed his face to the scanner bed, playfully experimenting, for the first time of many, with the effect of portraiture created through mass reproduction.

DRYPOINT

‘Drypoint’ is a medium that takes its name from the tool used to engrave the image into a metal printing plate. A special, very hard and sharp point—either metal or diamond—is used to incise the image into a plate made of a softer metal, often copper. This is an intaglio printing method (see later), as it is the depressed areas, the incised lines, as well as the burr— a raised, jagged edge to each channel created by the tool, left behind by the process of scratching the plate with the drypoint tool— that hold the ink, and create an image when printed. Because the plate has to be a very soft metal to be worked into, the plate degrades quite quickly, as its surface is liable to accidental scratches, and subjected to the pressure of printing. Over time, the contrast between incisions and negative areas is worn away and the burrs are flattened. To make a plate last for a larger edition size, it may be ‘steel-faced’, a layer of harder steel is added by electrolysis, after it has been worked into. Given that the plate can’t be reworked after the thin steel layer, printers may create several trial proofs ‘before steel-facing’, to check the image. Prints labelled ‘before steel-facing’, will have a slightly softer quality than those after, and as a rare form of proof, they may be worth more.

Drypoint is often used in conjunction with etching as a means of adding finer detail that is appealing for its velvety quality.

ENGRAVING

Refers to intaglio prints where the positive image is scratched into the metal plate manually. When ink is applied, it is these channels that hold ink and produce the image on paper when the plate and paper is passed through the press.

ETCHING

Another intaglio print medium, in etching, the incisions on the metal plate are created through chemical reaction. First, the plate is given an acid-resistant layer all over (known as the resist), then the image is scratched into this layer, exposing the metal where marks are desired. When the plate is next washed in acid, only the exposed areas are corroded, or ‘bitten’, reproducing the incisions created in the acid-resistant layer in the metal below. Once the resistant layer is removed, the plate is ready to be inked; the ink will adhere in the grooves and channels created by the acid and print a positive image of what has been incised. Lucian Freud made many etchings throughout his career.

Derivatives of this process include photogravure, also known as heliogravure, which uses an acid-resistant layer that is also light sensitive, saving the manual labour of engraving the resist and enabling photographic reproductions.

INTAGLIO

In intaglio prints, the image is etched into the plate, and when inked, it is the depressed areas, the carved marks, that retain ink and produce the print. This means the image is produced ‘positively’, in other words, the marks made are the marks that will eventually appear on the paper.

LINOCUT

In linocut printmaking, the design is drawn, traced or image transferred onto a sheet of linoleum, and then the negative space of the design (i.e. areas in which the artist does not want any ink printed) are carved away with lino tools. Characterised by the fact that the mark making produces negative space, and that it is harder to achieve a high level of detail through the manually demanding process of carving, linocut prints are usually recognisable by the fact they are highly stylised. This quality was put to deliberate effect by Pablo Picasso, who felt an affinity to ‘primitive’ art styles, and used the linocut to achieve a more raw, highly stylized print, such as for his print Femme Endormie (1962).

LITHOGRAPHY

The design is drawn onto a special kind of flat stone, usually limestone, or metal plate using a greasy substance. The stone is then treated with, causing a chemical reaction that fixes the hand-drawn image on the stone, leaving the negative space absorptive of water. When wet, these areas will repel the printing ink.

Lithographs can be recognised by the random dot-pattern seen up close—the result of the organic texture of the stone. This technique has been used by many famous artists from Pablo Picasso to Frank Stella, and even Andy Warhol early in his career, before he fell in love with screenprinting.

MONOTYPE

Monotype prints, or simply ‘monoprints’, refer to any print medium that only has the capacity to make one impression. They cannot produce editioned prints, and as a result are typically treated as original works.

OFFSET LITHOGRAPH

In offset lithography, the lithographic stone transfers the image to another surface which is in turn used to print the image—thus, the image is reversed twice in the process, and so is ultimately printed as identical to what is initially drawn onto the plate. Given that offset lithography now usually connotes a modernized, less laborious process, involving photosensitive metal plates that are digitally exposed, in a contemporary context the method is generally used to produce cheaper reproductions.

POCHOIR

Pochoir, French for ‘stencil’, is a means of consistently applying colour to a print by hand. It involves cutting or punching out specific shapes on a stiff material and placing it over the printing surface. Ink or paint is then applied, carefully avoiding the edges of the stencil. Pochoir gained popularity during the early 20th century as a means of producing colourful illustrations in books, fashion plates, and art prints.

SCREEN PRINTS

In this printing medium, the image is created using a stencil created on a framed screen of silk or similarly fine fabric. The stencil can be manually created on the screen, by applying the masking medium to the areas where ink is not wanted. More frequently, the masking is created by applying a photosensitive medium to the whole screen, layering a cut-out or transparent of the image, and exposing the screen to a light source. The photosensitive chemicals will be fixed by exposure to light, leaving areas not covered by the cut-out to become masked. To print the image, the printer or artist will squeegee ink through the screen onto the paper beneath, attempting to create an even layer of ink where the screen allows it to pass.

Multiple screens can be used to layer impressions and different colours. It is likely for this reason that screenprinting was Warhol’s medium of choice and is to this day practically synonymous with his name; Warhol was able to experiment with the composition of different elements and the layering and registration of different colours endlessly, thanks to his use of screens. Additionally, he used the photo silkscreen technique, which enabled him to use press photos, film posters or promotional portraits for iconic prints like Marilyn, as part of his meditation on the public status of celebrity.

WOODCUTS

Also known as wood engraving or a woodblock print. Much like in linocut prints, an image is carved away, only it is carved from the surface of a block of wood. When coated in ink, an impression is created from the block’s raised areas. Woodcut is one of the oldest forms of printing, and some of the most enduring prints are Japanese woodblock prints such as Hokusai’s Great Wave, from 1831, and others from much earlier. But it is no less inspiring to contemporary artists, including Damien Hirst, who released woodcut editions of his iconic Spot prints.

What makes a print valuable?

The cost of a print can vary depending on its popularity, rarity or quality. Some artists command higher prices than others. Signatures can sometimes – but not always – add to the print’s value. Its provenance and history can also be a major factor: if a famous collector once owned the print, or if it has been featured in a book or museum exhibition, can all contribute to its price.

Rarer editions are more valuable. If few people are selling a similar print to you – because other editions are lost or in museum collections – yours will be more sought-after by other buyers. Among the prints that are considered rarer are those that are designated as one or another kind of ‘proof’—read here to find out what that means, and which forms of proofs are worth the most.

Trends in the art world can also make a crucial difference: if an artist is in the news or has a major exhibition, there is usually a renewed interest in their work and often an increase in their prices.

Prints that are in good condition will be more valuable than prints that are damaged or poorly stored, so take care of your print and it will take care of you.

How do I look after a print?

We recommend you take your print to a reputable framer – have it mounted using the right materials and placed under high-quality glass. Don’t trim your print to fit into a smaller frame, as this will affect its value. Hang your print away from direct sunlight and keep it away from moisture and fluctuating temperatures. Carefully store any paperwork that came with your print too, especially certificates of authenticity – you will need these if you decide to sell your print later.

Start your collection today by browsing our list of artists, and sign up to MyPortfolio to create and manage your collection of prints and editions.

- Updated 18/08/2023 by Essie King