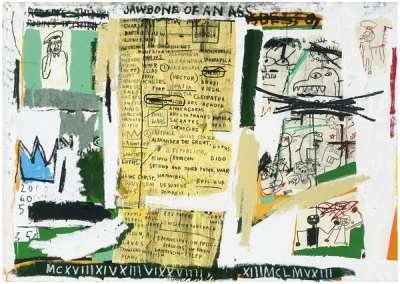

Jawbone

Of An Ass

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Jawbone Of An Ass series recalls, in its title, the artist’s persistent obsession with anatomy, alongside many other allusions, some biblical, and many to historical antiquities, such as Cleopatra, Carthage and Pompeii. Underlying the cacophony of allusion is Basquiat’s critique of contemporary society’s confused and whitewashed history.

Jean-Michel Basquiat Jawbone Of An Ass For sale

Jawbone Of An Ass Market value

Auction Results

| Artwork | Auction Date | Auction House | Return to Seller | Hammer Price | Buyer Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jawbone Of An Ass Jean-Michel Basquiat Unsigned Print | 14 Mar 2024 | Christie's New York | £24,650 | £29,000 | £40,000 |

Sell Your Art

with Us

with Us

Join Our Network of Collectors. Buy, Sell and Track Demand

Meaning & Analysis

Few Basquiat works demonstrate the extent of his vast cultural knowledge as effectively as Jawbone Of An Ass. First of all, there is the bible verse which the work references in title: “Then Samson said: “With the jawbone of a donkey, Heaps upon heaps, With the jawbone of a donkey I have slain a thousand men!”. The anatomical title of the piece also recalls the artist’s persistent obsession with the human form.

Jawbone Of An Ass mentions several icons of antiquity including Cleopatra, Scipio, Hannibal and Hamilcar, alongside ancient cities of historical significance such as Carthage and Pompeii. The use of roman numerals at the base of the image reinforces the work’s classical themes. The viewer scrambles to transform Basquiat’s cacophonous collection of references into a coherent whole. Wordplay predominates; words are repeated and twisted, with similar words juxtaposed (Socrates/Sophocles), creating a kind of lexical puzzle.

The unstructured listing of ancient places, figures and events (including the Punic wars, commonly referred to as “the longest and most severely contested war in history”) many of which met a grisly fate, presents a cyclical vision of history, where conflict and catastrophe is inevitable. Not only is the world of antiquity the locus of this recurrent destruction, but towards the bottom of the list appears references to significant moments of American history including “Louisiana Purchase” and “Emancipation Proc.”

Basquiat’s crown motif is ever-present, dotted around the image in various guises. Stars, explosions and battling figures surround the text chaotically, covered by layers of paint or crossed out in part. Just beneath the title can be seen a difficult-to-read ‘sbestos’, offering the possibility of an alternative title of ‘Jawbone of an asbestos’, offering a parallel between the jawbone of an ass as a powerful weapon and asbestos as a weapon of corporate greed.

This interplay of wordplay and sharp social commentary is reminiscent of Basquiat’s early career graffiti created together with Al Diaz under the moniker ‘SAMO’, which drew attention to social ills through incisive wordplay, undercutting accepted values. As Leonard Emmerling notes: “The SAMO project attacked the speciousness of materialist society. Basquiat and Diaz used their made-up religion as a substitute for all the value systems which they felt had falsely represented them, these ideas and systems in truth connoting no more than base economic interests”. Even though Basquiat publicly disavowed SAMO by painting ‘SAMO IS DEAD’ on walls throughout New York in 1980, the same approach to lexical experimentation is visible throughout Basquiat’s oeuvre.