The Skull, the Butterfly and God: Damien Hirst on Death & Religion

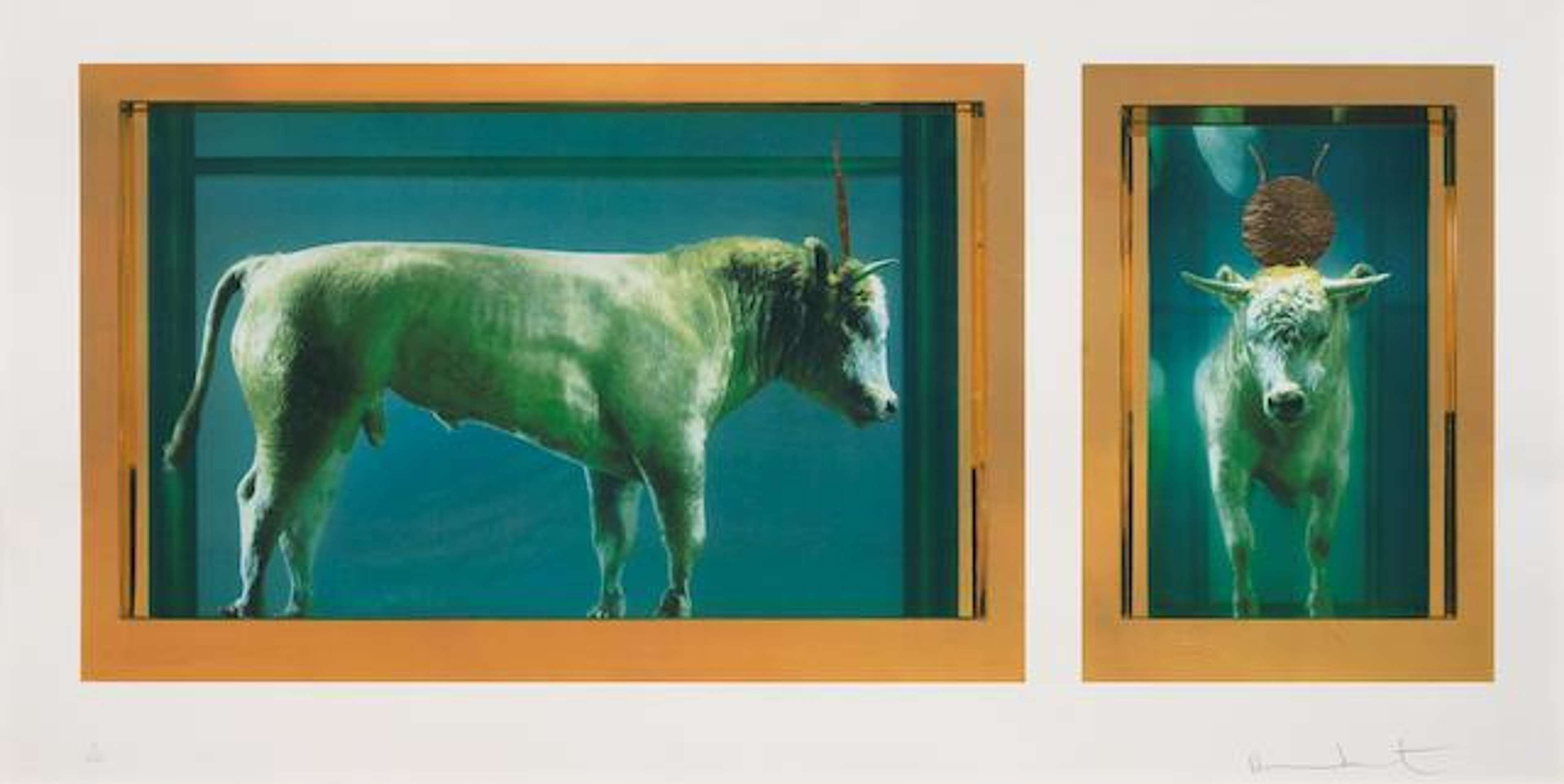

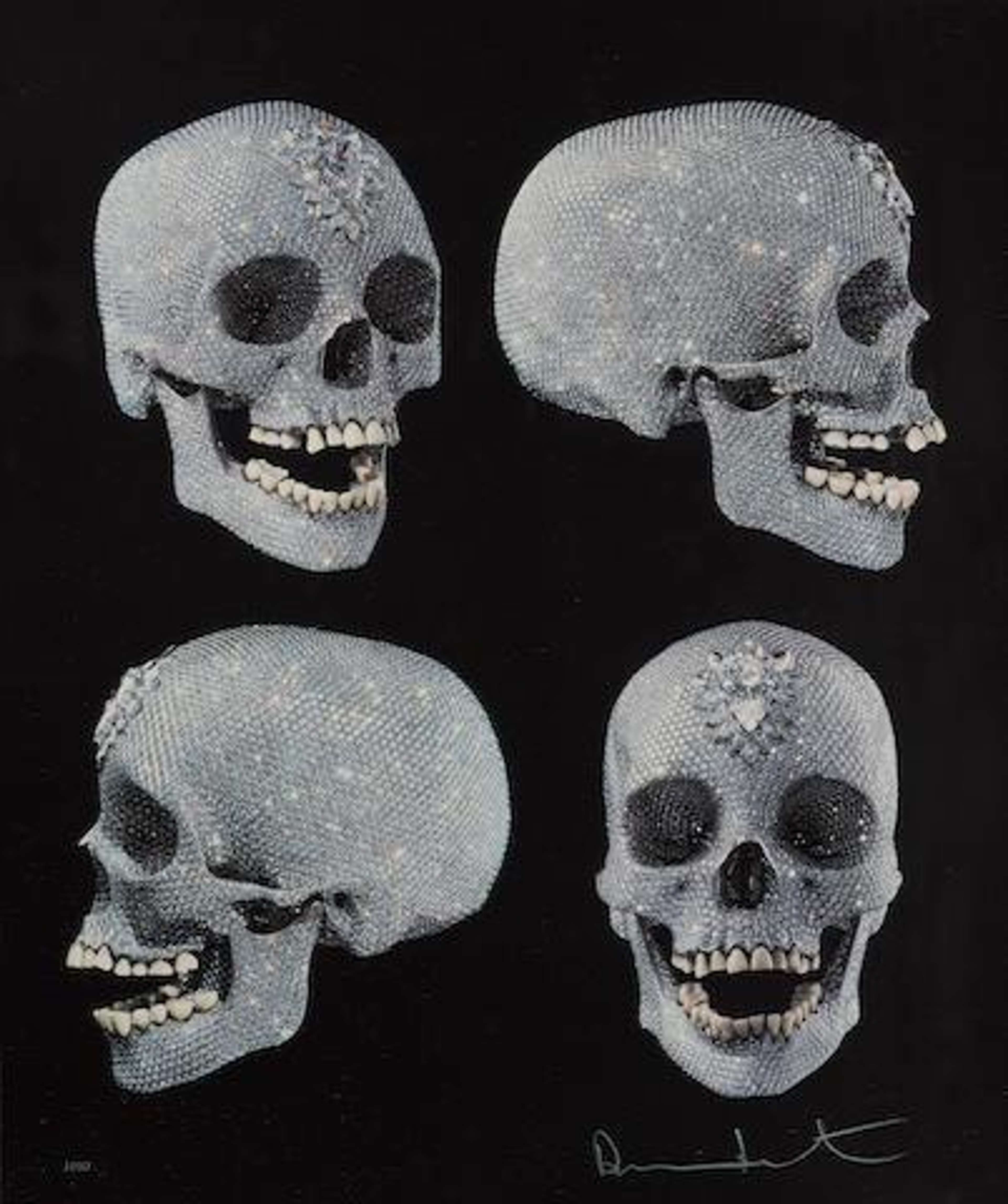

For The Love Of God (Four, Black) © Damien Hirst 2011

For The Love Of God (Four, Black) © Damien Hirst 2011

Damien Hirst

685 works

Once controversial Young British Artist Damien Hirst has often referred to himself as the art world’s ‘death guy’.

Hirst has spent much of his career courting controversy for his gory, grotesque - and sometimes disturbing - installations, which feature morbid, medicinal found objects, and animals, both dead and alive.

Behind these divisive works, however, is the artist’s deep, morbid fascination for death and religion: two far-reaching, universal themes which, he argues, are embedded in every single artwork created since the beginning of time.

From medicine cabinets to the skull and butterflies, in this article we take a closer look at some of the central motifs used in Hirst’s artistic meditations on death and religion.

Damien Hirst: 'The Death Guy'

Even before becoming a full-time artist, Hirst would express his all consuming fascinations with death by way of creativity.

One of Hirst’s most well-known photographic works, With Dead Head (1991), indexes the firm grip of these morbid preoccupations.

The photograph features a smiling Hirst, aged about 16. His cheeky grin does little to hide a sense of fear and disgust. Positioned alongside it, to the right of the image, is the frozen expression of a real-life severed head.

But is the photo real?, you ask. Well, yes. From the age of 16, Hirst would visit the anatomy department of Leeds Medical School, and worked part-time in a morgue. He took this photograph illegally whilst visiting a medical demonstration room.

Hirst found and enlarged the photograph in 1991 – a year which saw him hold his first two solo exhibitions in London, held at the Woodstock Street Gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA). These were entitled In And Out of Love and Internal Affairs.

Deeply grotesque – and stomach-churning – With Dead Head was instrumental in solidifying Hirst’s public image as an artist eager to shock and to broach the ultimate taboo: death.

By 1993, Hirst had started to experiment with a range of non-traditional media that would go on to define his controversial career.

That’s right. We’re talking about see-through tanks, formaldehyde, and flesh.

The first piece that saw Hirst bisect dead animals and encase them in formaldehyde tanks is also one of Hirst’s most famous artworks: The Physical Impossibility of Death In The Mind of Someone Living (1991).

Comprising a preserved tiger shark, encased in a translucent tank containing the preservative formaldehyde, the work is divisive to this day. Despite its apparent simplicity, however, it constitutes a purposefully confusing meditation on death. In a way, the artwork captures the flashing moment of death, preserving it for all time.

Similar in its remit, Mother And Child (Divided) (1993) is a firm nod to Hirst’s Catholic upbringing in Leeds. A subversive take on the Madonna and Child, it de-thrones a religious reference point that is canonical in holy and art historical contexts alike.

Mother And Child (Divided) (1993) was a harbinger of the New York showing of the epoch-defining Sensation exhibition, when a work by Chis Ofili – the first black artist to be awarded the prestigious Turner Prize (1998) – entitled The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) sparked fierce controversy for its pornographic subversion of its named religious subject matter.

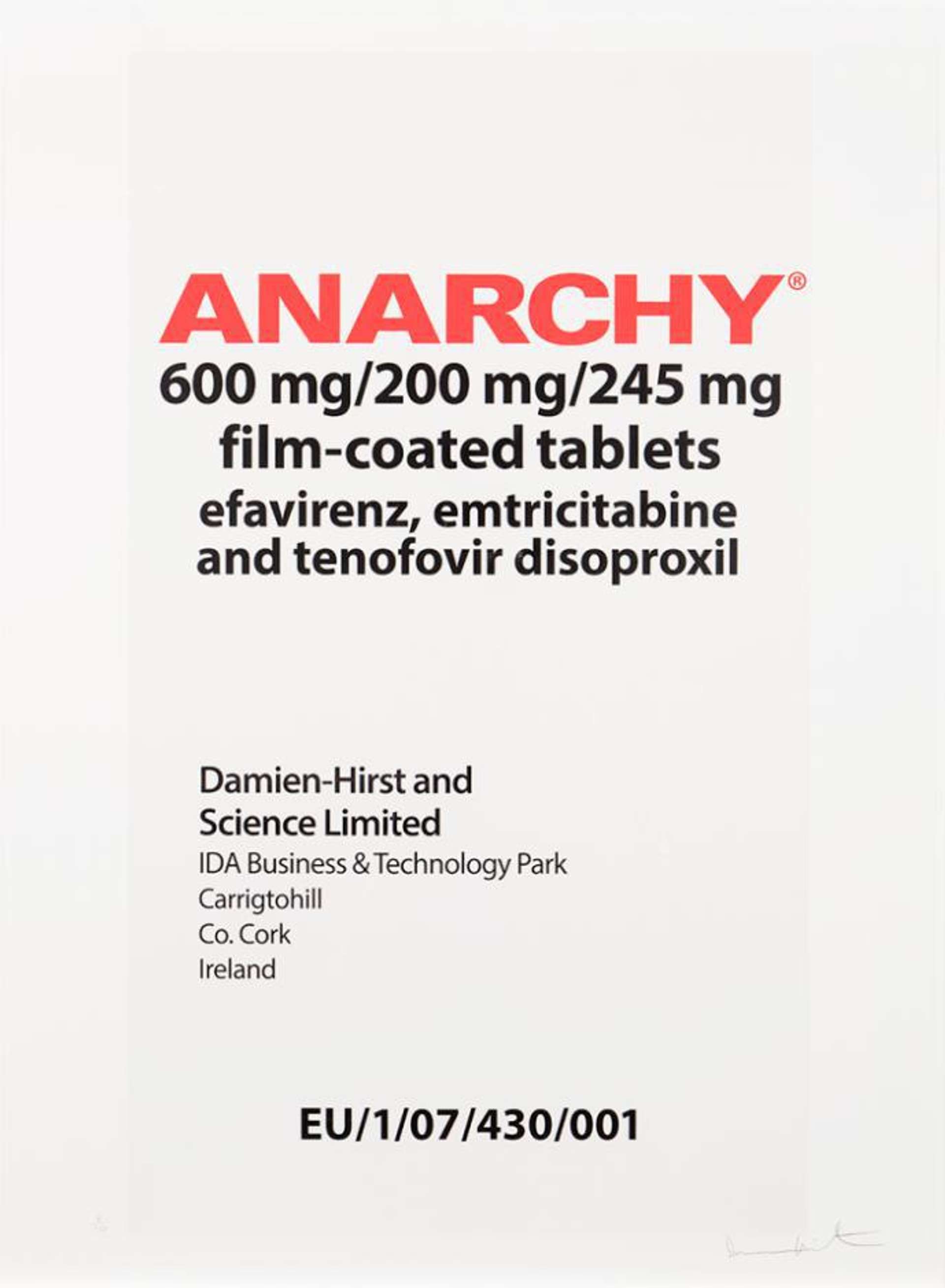

Damien Hirst and (Modern) Medicine

During his time at Goldsmiths, Hirst developed his understanding of the interplay between painting, as a two-dimensional medium, and sculpture, as a three-dimensional one. As part of this development, Hirst became interested in medicine as motif.

Hirst produced a number of minimal installation works inspired by American conceptual artist Sol LeWitt, such as Medicine Cabinets (1988). These works were made using his grandmother’s empty medication packaging, which he had requested she leave him in the event of her death.

Later, in 1992, Hirst produced the large-scale work Pharmacy (1992). Commenting on the work, Hirst once said: ‘With the Pharmacy (1992) installation I wanted to get a pharmacy and put it into the art gallery. But one where you actually think you’re in a pharmacy. You know, just to confuse you. It just makes you question everything.’

Beyond his obvious preoccupation with death, there’s a religious thread to Hirst’s fascination with medicine at this stage of his career.

Speaking in interview, Hirst confessed an interest in ‘new’ belief systems around this time. One of these systems was that of science. But why science? Well, in Hirst’s own words: ‘Science is the new religion, really’.

In 2000, Hirst combined religion and medicine in the large-scale work, Trinity - Pharmacology, Physiology, Pathology (2000).

Comprising three wall-mounted cabinets, constructed by Hirst himself, this work is chiefly concerned with a variety of corporeal - and medical - objects and models. These include foetuses, skulls, reproductive organs, torsos, and brain-filled skulls.

According to Hirst, the artwork is designed to be scary: ‘We’re all afraid of surgical instruments [...] I suppose there’s a kind of invasive procedure, isn't there?’

Damien Hirst's Skull Motif

Trinity (2000) was one of the first Hirst works to focus on the human body rather than its animal counterpart.

The artist’s fresh interest in corporeality would go on to find its ultimate expression in 2007, when Hirst produced one of his most well-known works: For The Love Of God.

For The Love Of God is a platinum cast of an 18th-century human skull.

Encrusted with diamonds by diamond specialists Bentley & Skinner, the sculpture cost a total of £12 million to produce.

Diamonds were key to the work, according to Hirst. Despite their material ‘value’ – an attribute of much Contemporary art that Hirst has been both quick to question and capitalise on – diamonds are, according to the artist, the ultimate ‘antidote’ to death.

The religious focus of the work’s title came from Hirst’s mother, who would exclaim the phrase ‘For the love of God!’ whenever a young Hirst had what he called ‘crazy ideas’.

The piece has since inspired a series of limited edition prints, also entitled For The Love Of God. This comprised an etching outlining a visual concept for the piece, entitled For The Love Of God, Beyond Belief (2007) and a limited edition photographic print depicting Hirst’s diamond skull, issued as part of Comic Relief in 2013.

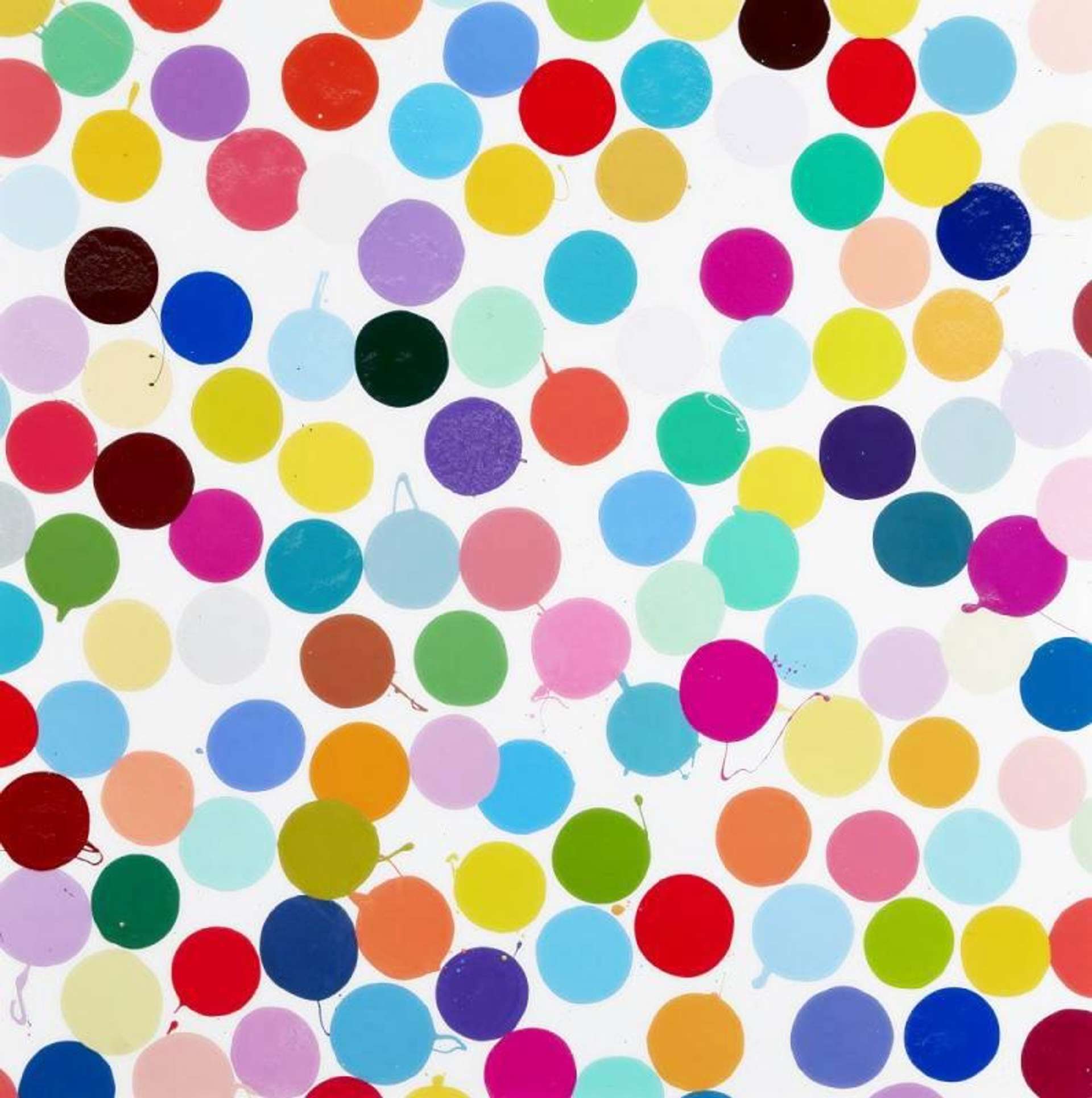

Hirst and the Butterfly

Although Hirst’s use of flies in the A Thousand Years (1990) was his first time using live animals in his art, the artist is arguably more famous for his long standing engagement with another insectile creature: the butterfly - a symbol of resurrection in the Christian tradition.

In 1991, Hirst held his first solo exhibition. Entitled In and Out of Love, one half of the exhibit comprised a room filled with life butterflies. A conceptual treatise on the circle of life and eventual death, the artwork that filled this room was entitled In And Out Of Love (White Paintings And Live Butterflies).

It consisted of an artificial humid environment designed so that butterflies could breed, hatch, and fly free until they died. At the centre of the room, a white table held bowls of sugar solution which the butterflies could feed on.

The exhibition was extremely divisive and angered animal rights activists. The most shocking aspect of Hirst’s installation, however, were the 5 primed canvases that adorned the installation room’s walls.

These had pupae (butterflies in chrysalis form) attached to them. Plants were positioned directly below the canvases, to attract butterflies to settle on the canvas surface after they had hatched.

In an interview with curator Ann Gallagher, Hirst identifies his love of Victorian curios as central to his butterfly-based artworks.

This chance find, made by Hirst in the early part of the 2000s, birthed another of his most famous butterfly-inspired works: Doorway To The Kingdom of Heaven (2007).

Evoking stained-glass windows or religious screens, this artwork comprises carefully arranged, real-life butterflies and a variety of bright hues of household paint. Its title references words uttered as part of the Beatitudes - the blessings given during the Bible’s ‘Sermon on the Mount’.

Combining Hirst’s love of death and religion, the butterfly - and its use within the paintings - serve to highlight the redemptive qualities of art.

Hirst’s butterfly motif has also appeared in several print-based series, including I Love You, It’s A Beautiful Day, The Souls, and The Souls On Jacob’s Ladder Take Their Flight.

Browse our Damien Hirst prints for sale or get a valuation here.